The beautiful Royal Albatross (Diomeda epomophora epomophora) shown with its new chick at Campbell Island during the summer of 1965. (photo: Colin Clark)

The beautiful Royal Albatross (Diomeda epomophora epomophora) shown with its new chick at Campbell Island during the summer of 1965. (photo: Colin Clark)

CAMPBELL-RAOUL ISLANDS' ASSOCIATION (INC.)

NEWSLETTER Vol 2 Number 10 MARCH 1974

Association Officers 1973 - 74

Patron

Air Vice-Marshall A. H. Marsh C.B.E.

President

Bernie Maguire

| Secretary | Treasurer | |

| Peter Ingram | Bill Hislop | |

| Committee | Honorary Members | |

| Richard Lovegrove | M. Butterton | |

| Peter Shone | H. Carter | |

| Tom Taylor | Capt. J. F. Holm | |

| David Leslie | I. Kerr | |

| Noel Caine | C. Taylor | |

| H. W. Hill |

Newletter Editor

Peter (Pierre) Ingram

"The Islander" is the official quarterly bulletin of the Campbell-Raoul Islands' Association (Inc.) and is registered at the Post Office Head quarters, WELLINGTON, for transmission through the Postal Services as a magazine. All enquiries should be addressed to: The Secretary, CRIA (Inc.), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON. Contributions to the bulletin should be forwarded to the Editor, CRIA (inc), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON, and subscriptions to the Treasurer. Current membership rates are $3 per annum.

_______________

SQUASH EVENING ••• SQUASH EVENING

We have contacted most Wellington members by phone at the time you read this and it promises to be a good gathering. Should we not have contacted you as yet - here is the score:

A games evening is to be held at John Reid's Courts, Salamanca Road, Kelburn, on the Friday of 19th April, 1974, from 1900 to 2300 hours. If you intend playing squash, white soled sneakers are required on the courts. Racquets and balls will be supplied.

Indoor bowls and pool can also be played, or you might prefer a quiet corner and a game of cards. Drinks will be available at normal wholesaler rates.

A door charge to cover the evening's rental has yet to be calculated, but judging by the numbers that intend coming, it will be around a dollar a head.

Bring a friend along if you wish. Looking forward to seeing you all.

The Committee.

_________________

Have you paid your 1973/4 subscription yet. We note some 68 members have still to perform this necessary duty. A reminder slip appears in the centre of this bulletin if you haven't done so.

*************************

Editorial: A TIME FOR PASSING ON.

It will be at the coming Annual General Meeting in September of this year, that I must with some regret, tender my resignation as editor to 'The Islander.’ My first issue was in December of 1970, after Richard Lovegrove had licked this small publication into shape and to which I have added little modification in these last four years.

Now I find my commitments to other organisations as well as a young family, and the widening gap of time, a serious handicap to my ability to maintain the necessary contacts and deadlines. Noticeably, I have used the bulletin as a vehicle for historical facts and articles, because, as I pointed out some time ago, more material was obviously to be found in the last 150 years rather than the last five.

In retrospect, I find the argument not particularly sound, for a well informed young member might see the case in reverse, endlessly drawing on contemporary developments and happenings as a far more fruitful source. This truly is the atmosphere in which the future 'Islander' should exist.

As a contributor in the years to follow, I look forward to having adequate time to explore and research the history of the Kermadecs - a subject which I have had to partially shelve while I have been editor. Although I may never attain Ian Kerr's thoroughness and exactitude, the example has been set and it is my duty to follow it.

___________________

To Revive an Old Itch

I would say the majority of the appreciative audience which filled 150 seats in the National Museum's theatrette last Monday night (25th February), were there to learn a little more from a favourite tutor. Certainly Sir Robert Falla's lucid and informal delivery on the Auckland Islands as a subject, made for easy listening and temporary relief from the nightly disciplines of television.

To a small minority in that audience, must have come a feeling of nostalgia and revival of dormant knowledge as Sir Robert flicked his way through a series of selected colour slides. Although I sat on the very fringes of this elite group, my Campbell Island experiences, coupled with having seen countless photographs and read several books on the Auckland Islands, made me feel a bit of an old hand - a pleasant feeling in which I secretly basked for the duration of the lecture.

The evening came as a climax for the time-expired Auckland Island's display just off the main hall. I suppose all that historic bric-a-brac and beautiful colour photographs must now be boxed and go to the back of the queue in the Museum's dark vaults. Thousands of interested visitors must have learnt something from that three month display - and made the minority yearn for the mobility of youth.

The half-way house beauty of the Auckland Islands is a picturesque blend of sub-antartic Campbell and sub-populated Stewart Island. The tight foliage of Southern Rata has a happy alliance with the beautiful plants and shrubs seen further south. Sub-antarctic sea birds live on the doorstep of the forest domains of the tui and bellbird.

But towards the end of the evening, when Sir Robert presented the NFU film, 'Adams Island', that odd hollow feeling returned. As I watched a soaring Sooty Albatross silently accept the ridge's turbulence, Phillip Temple's final paragraph in 'The Sea and the Snow' came truly home …. "the prions mimed in the azorella, the skuas stalked them, the penguins paraded and squabbled. The seals moulted and slept, irritated, not awed by our presence. Though we laid claim to the land and the mountain, we were a rare, migrating species with a delicate grip on existence. They were the true children of Heard (Island)."

How often I felt and knew that on Campbell. The beauty of the sub-antarctic is for the lucky few to visit - never to keep.

*************************

MEMBERS COMMENT

Trevor Buck writes in from Queenstown:

I hope some of the following information may assist you in compiling a record of some of the chaps I recall which were resident on Raoul Island during the time I was there. My period was 21 July, 1944 to 9 October, 1945. Some were only there for relatively short periods but I will try and give you a picture of them as I recall.

I went to Raoul on the schooner "Tagua" leaving Auckland on 17 July and arrived 21 July, 1944. The Skipper was Capt. Mathieson and on this trip he had his wife with him. Besides the crew the only passengers were a Cook (can't recall his name as his stay was short) and, my Boss, Alan Gardiner, who was returning for a second term. We were both army outfitted, myself a Private at the age of 17 and Alan a Sergeant. Our concern was Radio Operating, Ionosphere recording and 3 hourly Met reports.

Those who left the island as I arrived were 4 army coast watchers, the last vacating the huts at Boat Cove and surrounding knobs. Also leaving was Alan W.W. Ingram (known as Inky) who I was to replace.

The Manager at the time was Dick Horsefall, a little chap, who left a few weeks later. He was replaced by Ted Davidson who remained throughout my stay.

Others as they come to mind are:

STUART KINGAN: an Ionosphere specialist who had made most of the equipment. It didn't look too flash but worked like a charm and he was dedicated to it. His ambition was to bounce a radio wave off the moon and he was well advanced with it when the Americans bounced a Radar Beam from the moon which made him loose heart in his own project.

HERB PICKERING: radio operator etc, 1943/44.

LES HACK: Radio operator etc 1944 to early 1945. Les was to stay a full term but events proved otherwise, as another chap…

JOE BRODIE: was passing through, on the 'Tagua', enroute to Pitcairn but Joe was so sea-sick he wouldn't go any further so Les took off in his place. I think Les went back to Raoul again later.

TIM STEVENS: Mechanic, a good one too.

MORRIE BEVERIDGE: Farmer assisted by Ted Doley.

ALEXANDER LITTLEJOHN: Cook, known as Scotty and quite advanced in years, and

CHARLIE ….. ? Roadman, who kept the road to Boat Cove up to navigatable standard.

SPUD MURPHY: Farmer, replacing Ted Doley. Spud had terrible eyesight. He brought 3 pairs of glasses with him but they were soon broken or lost. To find the cows he struggled down to the radio shack, knocked us up, and asked for us to point the cows out. I do believe his eyes improved during his months without glasses.

DOUG McKAY: Mechanic, replacing Tim Stevens.

JIM HARTIGAN: Radio operator etc, replacing Herb Pickering.

"Others I recall are by incident only. When I arrived there was a chap engaged on goat extermination, which he did very well with the aid of his dog. "At one time 3 chaps came up to cut 'knees' from the Pohutukawa trees for boat building. They were there for several months and they got a lot of them. "At Xmas 1944 there were 9 whites and 7 Niueans on the island. The only Niue person I can name is JOHN TAMATI. John had been on the island for two terms as a labourer and came back for a 3rd term to work with us in radio. "I suggest that some of those I have named are no longer with us but that is life. We had some good times there and went through some big earthquakes.

"Good luck to you fellows in keeping the spirit alive and I must say you are doing a fine job."

(Many thanks for your good wishes Trevor. Les Hack, of course, is a well known member and is in Insurance in Wellington. Quite a few Wellingtonians will know Jim Hartigan who is now in the upper ranks of Communications for the Ministry of Transport. Dick Horsefall, I last saw in Lauthala Bay, Fiji, when he was Stores Manager for the Ministry of Works in 1965. He would be a long time back in New Zealand by now, for they flogged his building to make part of the complex for the University of South Pacific - Editor.)

_________________

And from Bob Rae (C 1958/9, 1960, 1963/4) in Auckland:

"1 have a small bone to pick with Peter. That is in the last "Islander", on the Yesteryear page, re 'Greater Things to Come', I will put you in the picture regarding these ships, as you seem to have the story wrong. At the time that the 'Achilles’ was in action with the 'Graf Spee', the 'Leander’ was at Auckland under twelve hours notice for steam, then on January the 4th, 1940, she sailed with the First Echelon to Sydney then returned to New Zealand. I will now give you the movements of the 'Leander', which may be of interest for 'The Islander’. On August the 30th, 1939, she took a small contingent of some 30 troops from Auckland to Fanning Island, this being a communication and cable station which lies about 3000 miles from New Zealand. On her return, she then left Auckland to visit the sub-antarctic islands to look for likely bases for German raiders. The 'Leander' arrived at Campbell Island on the morning of the 28th of September. After an examination of all the bays and inlets, she left for Auckland Island, arriving there next morning and anchored in Port Ross. After inspecting this locality, she steamed along the East side of the main island and lay-to, two miles to the seaward of the entrance to Carnley Harbour, in a gale, with visibility of about six miles between the rain squalls.

"Nothing suspicious was seen in the Eastern end of Carnley Harbour or in the inlets further up the coast, so she returned to New Zealand. The 'Leander' was back in this area again in November to look for the signs of the German steamer 'Erlangen'. There is little doubt, however, that this ship was lying in a remote anchorage in Carnley Harbour at the time of the 'Leander' making her first visit to Auckland Island.

"'Erlangen' sailed from Dunedin on August 28th, 1939, for Port Kembla, New South Wales, where she was to have coaled for her homeward trip, but she was sighted two days later hove-to off Stewart Island in weather that did not necessitate precaution. According to German accounts, she had been ordered by radio from Germany not to go to Australia, but she did not have sufficient coal to get to the distant neutral waters of South America, so the Captain decided to go to the sub-antarctic islands to see if he could find fuel to help to get there.

"They lay concealed at the head of North Arm, Auckland Island. They were there for five weeks while the crew cut Rata wood of which some 400 tons was loaded. They made sails out of hatch covers and what spare canvas they had, she sailed on 7th October, and after a passage of five weeks arrived at Puerto Montt, Southern Chile.

"The 'Erlangen' ultimately made her way into the Atlantic. She sailed from Mar Del Plata, Argentine on 24th July, 1941, and was intercepted by H.M.S. 'Newcastle'. She was set on fire by her own crew. An unsuccessful effort was made to tow her into Uruguayan waters but she sank.

"In April, 1941, when the coast watching station was established on the Auckland Island, it was found that about five or six acres of bush had been felled at the head of North Arm.

"Well Peter, that is the story as I know it, so I hope that will be of some use to you."

(Well it certainly was Bob and I thankfully reproduce the details here and now. Harking back to the last issue of the 'Islander', other readers may have noticed my error when I dispatched both the 'Achilles' and 'Leander' to hunt down 'Graf Spee’. Thankyou Trevor and Bob for writing in - these are the sort of letters we want - Ed)

***********************

AN EXTRAORDINARY BUSINESS

or special general meeting is to be called on the evening of Saturday, 22nd June, 1974, directly preceeding the Annual Film Evening which will commence at 2000 hours. The subject to be raised is a proposed amendment to Section 5 of the Association's Constitution, 'Associate Membership.'

The motion to be put by the President, is that the first sentence of this section …. "Associate Membership will be available to persons who are, or have been associated with either island, on being proposed …. " (page 212, vol 2, no 9, 'The Islander.') be amended to read …. "Associate Membership will be available to persons who are, or have been associated with either island, OR THOSE PEOPLE INTERESTED, on being proposed …. ".

This suggested amendment will be to encourage bulletin receivers on the free mailing list of 'Interested Parties', to become financial and assist in the maintenance and possible future expansion of 'The Islander.' At present, our total annual income is necessary to provide the quarterly issues.

Full Members are therefore requested to proceed to the film audience at 1930 hours in the Lecture Hall at Kelburn and vote on this matter. Quorum for such a meeting is 15 Full Members.

Secretary

*********************

LARGE AREA OF CHATHAM ISLANDS TO BE SET ASIDE AS RESERVE

Evening Post, 4.2.'74.

One of the most important purchases of land for reserve purposes by the Government in recent times had been successfully negotiated in the Chatham Islands, the acting Minister of Lands (Mr Faulkner) said today.

The property, the 2360 hectare Glory Block on Pitt Island, was formerly owned by P. Feron and Son, Ltd., and parts had been used for farming. The Government intended to fence two blocks, with an area of about 1215 hectares, and set these aside as reserves he said.

"The Chatham Islands have long been known for their exceptionally interesting flora and fauna, including many species and subspecies found nowhere else, but despite this only a very small proportion of the islands is so far reserved to preserve its botanical, ornithological and entomological values", said Mr Faulkner. "Already five unique species of birds have become extinct in European times and another eight species are rare or endangered."

No endemic plant was in danger of extinction but there was very little vegetation which was not severely depleted in the variety of plants it contained and this was reflected in the scarcity of bush birds. One of the proposed Glory Block reserves contained the only surviving large area of forest in the Chathams and by fencing this to exclude cattle and other livestock it could be expected that the forest cover would regenerate and give the endangered bush birds a better chance of survival, said Mr Faulkner

"The other proposed reserve, taking in the southern portion of Pitt Island was important for three main reasons he said. One was because the Chathams were rich in endemic insect species, particularly in lepidoptera and weevils; secondly because this unique fauna was still inadequately studied and the third reason was because the early collection of insects by Pascoe and Thomas Hall were from Pitt Island. It was understood that the new reserve proposal were fully supported by the Pitt Islanders , he said."

____________________

(Tunes of Glory: We rode out from the homestead in the early light of the fourth day of strong south-westerlies that had sent the 'Holmburn' scurrying for the shelter of Owenga. The wind had moderated and there was a definite prospect of the low overcast breaking and clearing by mid-day.

The station manager, Bill Moffat, was a squat extension of his horse, a trifle bowed by last night's rum, but mostly in position he had comfortably adopted many years ago. I rode happi1y bandied in his wake, my new found confidence over the horror of horses cancelling any time for thoughts of ill-health.

We had a project - to inspect and shoot back the wild cattle at the southern end of the island. Twenty-six miles on one of the greatest adventures I have ever experienced. Canadian Club would have had a flag day.

By mid-afternoon we had ridden down into Glory. W slipped from the horses and clumped into the ancient shepherds' hut. Jim threw himself onto a sacking bunk without hesitation and I thankfully followed his example, staring up at the smokey cei1ing as soon as I had completed my three-pointer.

For a while, nothing but the sea and the rhythmic ripplng of grass from the rear of the hut filtered through. Then Jim started to slowly grunt out the past from the depths of his bunk which was slowly degenerating into a hammock.

'Glcry' had been a 100 ton brig engaged in sealing round Pitt Island in the early days of 1827. She had accidently bumped her way ashore in a heavy swell and nothing could be done in time to warp her off. In the style of the times, the crew prepared the long boat and set off for civilisation, finally arriving at the Bay of Islands a month later. Much later the sheep came, but this wild corner of Pitt had her name, and perhaps it wasn't too misleading at that.

It was a hauntingly beautiful place, wild and green in the late afternoon sun as we rode back into the high country. I turned away to catch up to Jim and knew then that Glory would be a lifelong memory.

Pierre.)

********************************

|

|

|

|

|

|

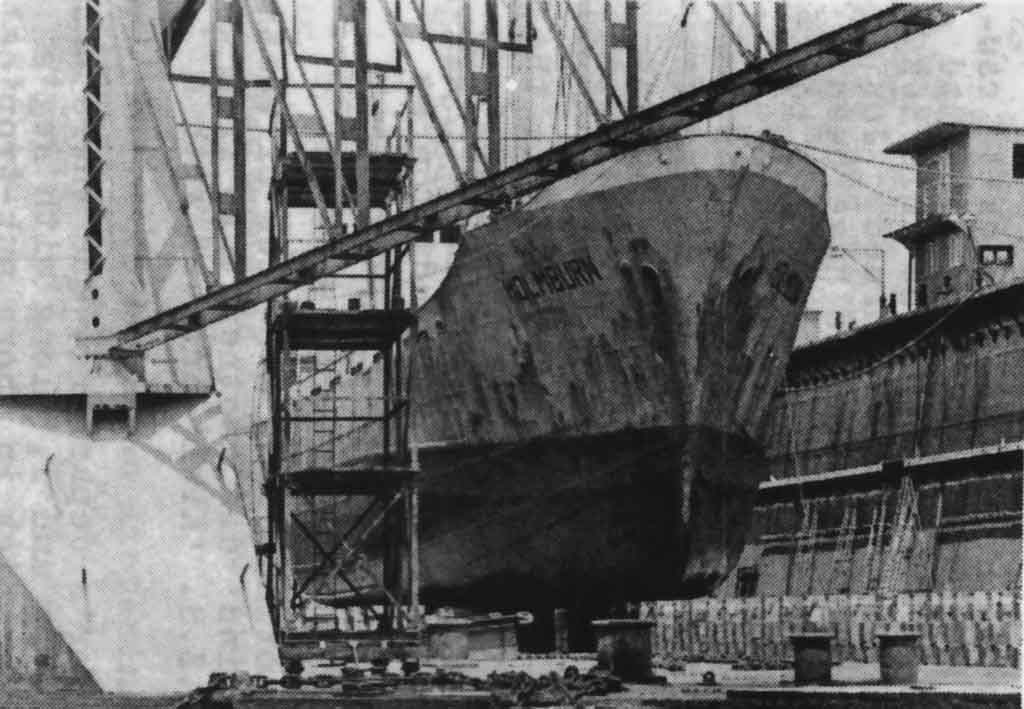

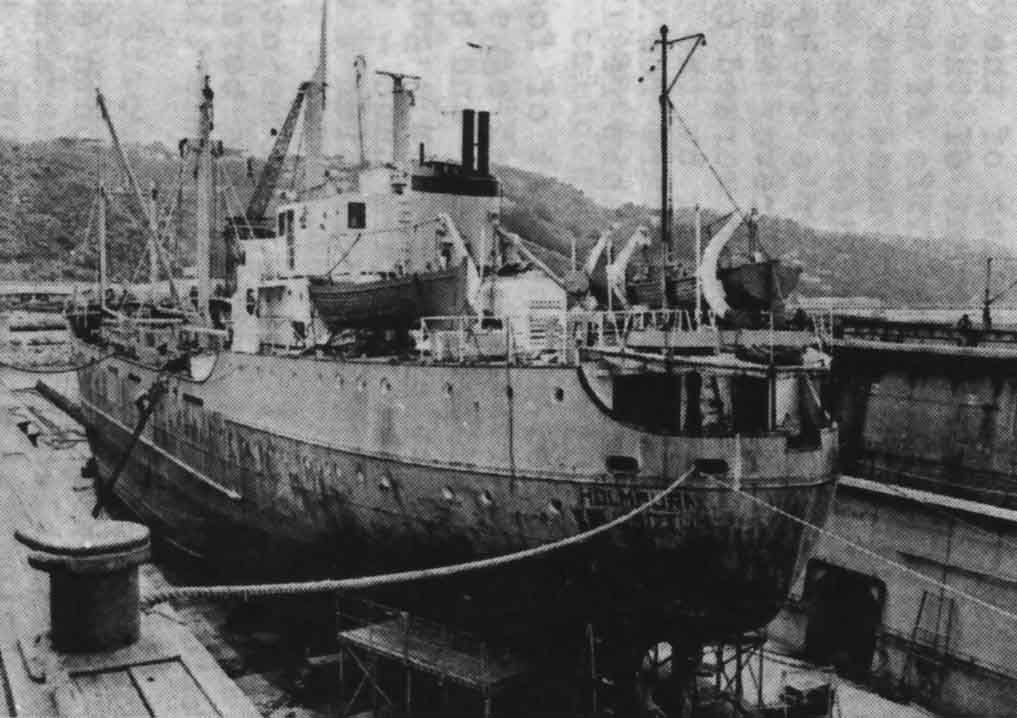

| MV Holmburn has no trouble resting her 245 feet in the dry dock at Wellington while awaiting survey after the 1973 servicing cycle. )photos: Pete Ingram) | ||

********************************

Short Story. FRAGMENTS OF A LONG SUNDAY

By Len Chambers.

I always admired those Norfolk Pines, and still think of them. They symbolize one of the most peaceful passages in my life. A feature of the northern side of Raoul Island, they stood gracefully tall and silent - stern sentinels - swaying proudly when the wind made mockery of their neat Christmas tree forms, contrasting with the tangled Pohutukawas dominating the volcanic landscape.

Those slender giants were really something. They were a special breed - alone alongside the Pacific - though they shared the same latitude as their brothers on Norfolk Island, a thousand miles away. Maybe that was the reason for their aloofness, not everyone was associated with the 'Bounty' descendants from Pitcairn.

They were visible from passing ships for miles on a clear day when the island basked in its blue costume of sea and sky. And they were helpful too, as a windbreak for the Niue Islanders' camp, a settlement of huts situated in hollow segregated from the main village, half a mile East at Fleetwood Bluff.

From the camp, you travelled along a dust bound road, stretching over a ravine and up through a cutting of sandstone and pumice, to pass the radio statnon on the left, then the cow bails before the village. A workshop, powerhouse and other outbuildings about a hundred yards from the hostel, surrounded by vegetable gardens, a tennis court and the steep sloping paddock of the Bluff, where Angus, the brown and white bull, was usually to be found.

When I first stepped out of a basket onto Fishing Rock, I knew, along with Johnny and Trevor, that I was glad to be on firm ground, even if the first impression was awe inspiring. I glanced up at the cliffs and it seemed that we were on the edge of a landslide, waiting to be buried.

A tap on my shoulder. "What's your name?" I turned and gripped an outstretched beefy paw, it belonged to Reg, the island administrator. A series of names were mentioned, I forgot them immediately. I was more interested in my surroundings - how the hell were we going to scale that face? I could see no sign of a track.

It was Trevor, the farmhand, who eased the tension a bit. "Hell, the sheep here must be crossed with goats." "Maybe they fly," I replied, shooting a glance at the pattern of red rock that had been formed by the elements over the ages. The sculptor had done a terrific job - the grooves and projections were almost symmetrical, and the boulders, with their hollows, high and low faces smoothly swept, would have done justice to any sculptor.

I turned to help unload a basket of cargo into a tray hooked to a steel sling dangling from the pulleys of a flying fox. It didn't take long to transfer the cases and other gear. Then a signal was given to the 'fox' operator by ringing an old type telephone, and the tray lifted to glide away, the pulleys singing over the wire ropes in their climb towards the winch house sitting on top of the cliff.

"I wonder if that's how we get up there?" Trevor said, nudging me. "I'm not too keen," I replied. "There's a track up", one of the men said, pointing. "You can't see it though. Too much bush."

A few tray loads later, we were straggling up the steep zig-zag towards the winch house and road. From there, the sea looked as innocent as a baby's bathwater; as if it wasn't guilty of the contortions it had made the 90 ton 'New Golden Hind' endure on the ten day trip. But the sea wasn't wholly to blame; a hurricane, with a demon packed force had tortured us for four days. It was a relief to be ashore.

We scrambled aboard the truck's tray- about fifteen of us -and flopped in various positions on the cargo. Then the Niueans start singing, and it was like a heavenly chorus after the roar of wind and sea.

There were always feelings of joy and sadness when a ship arrived, mail to be read and written to catch the outbound ship, personal messages to be passed on - and there was the grog supply. This was a delivery right from the Gods - but it didn't last long enough. When the ship left, lips, parched by perpetual heat, soon swallowed any that was around.

The ship was a day out from the island when Reg took me around the farm to show me what had to be done with the RD 7 Caterpillar. There were tracks to be cut with the blade, discing, harrowing, grass seed to sow and road maintenance.

The track to Bell Flat wound past the Niue camp to a slope between the taro garden and watermelon patch. As we passed the camp, Reg stopped me. He pushed his straw hat to the back of his head. "Just a word of advice, boy," he said. "The Niue camp is what you might call out of bounds." "Why?" "Ah well," he sighed with a broad smile, "It doesn't pay to fraternise with them. They're only natives you know." "Dont see any harm in it," I answered, remembering the Public Works camp at Trentham, where our row of huts was called 'Night Club Alley' and Maori and Pakeha men and women mixed freely. I thought of Kathie who had often stayed weekends with me. Deep olive skin and shining black hair. She was beautiful. "I've worked and lived with Maori people back home. Can't see any difference in these jokers."

Reg prodded the ground with the stick he always carried. "Where I come from we don't mix with blacks." "Where's that?" I asked. "Australia," he said proudly. "Been all over it."

We continued towards the taro patch to the beat of his tapping stick. "They're a bad lot, these islanders, you can't trust ‘em." He paused. "They will persist in making home brew, that's why I'm warning you." He pointed his stick. "Take heed young fellah. We've had one of our men go berserk with the grog. We don't know if it was the brew of whisky. But whatever it was, he threatened some of us with a rifle."

We passed through a grove of nikau palms surrounded by a bed of arum lilies. I often thought they had the gift of harnessing the heat and moisture to produce their musty fragrance. Reg pointed to a slight grade on our left, at the fringe of the steep, pohutukawa clad slopes of Pukemiro Hill. "I'd like to bulldoze a few terraces up there. But," he emphasised with a wave of his stick, "this place comes first."

We were standing on Bell Flat. I looked across the area with its quilt of new grass beside a strip of land, just disced and ready for harrowing. "That's what you have to do," he said. "Bring that into grass." He leaned forward, "and down there - see." I nodded and surveyed a distant stretch matted with burnished tufts of buffalo grass around clumps of Ngaio. "Well," be beamed, "all that stuff and the protruding boulders have to be bulldozed over the side."

My duties included breaking in the land, operating the crane at Fishing Rock, and the maintenance of the seven mile road to Boat Cove, on the south side of the island. It was rough and winding. A case of scraping up loose rock with the bulldozer blade, patching the road with pumice; or a blue binding rock quarried from the side of the crater, adjacent to the road, and hand loaded into the Ford tip truck. Scouring was a problem. The sudden, heavy downpours of rain caused a lot of damage. The road had to be kept open at all times in case of an emergency, or when the sea was stirred up by strong north east winds and the open roadstead of Fishing Rock wasn't safe to use.

I'll never forget the first day I went out with Caterpillar to harrow Bell's Flat. I had a Niuean as my offsider. His name was Tofilau, but he was known as Hoppy. His job was to pick up any stones he could see and place them in heaps to be collected later. Hoppy was a big fellow, with broad sloping shoulders, and when he walked, it was a slow casual gait - as if time didn't mean a thing. But he was always on the move.

Hoppy gave me a wave for morning smoko at ten o'clock, after boiling a billy over a fireplace he had made with stones. I was glad to get off the dust stirring machine to sit in the shade. Hoppy poured tea into enamel mugs for us and said, "Do you take milk and sugar, Kapisiga?" I nodded. "Yeah - thanks," as I sat on a boulder and lifted a denim cap off my head. "It's hot". "Vele Lahi," he agreed. Hoppy opened a square biscuit tin, which he'd collected from the hostel cookhouse, and lifted a parcel containing butter, sliced bread, cut meat and tomatoes. He handed it to me. "I think yours Kapis iga." "Thanks," I replied, wondering why he said it was mine. When he opened his parcel of big square cabin biscuits and a piece of cheese, I realised. You need strong teeth to make a mark on that brand of biscuit. He glanced up at me shyly from where he sat on his haunches as he dipped his biscuit into his mug to soften it. H e took a bite, gave me a benign smile and chewed distastefully. "You like them?" I asked. "Not much - Kelea."

"Have to. Reg, he say so." "Why not bread?" "Bread not all the time for Niue boy. Only for palagi." "Do you like bread?" "We like bread, but not always have it." "Right," I said. "Do you want some?." "What about you, Kapisiga?" "Don't worry. Do you want some?" "What about Reg? What he say?" "To hell with Reg. Do you like bread?" "Yes." "Well Reg doesn't need to know. Does he?" "I not tell him." "Right, neither will I." I leaned forward. "Hoppy." "Yes Kapisiga." "You and I will be working together for a long time." "Yes." "So," I continued, "what ever I have to eat, I share with you."

He laughed and pointed to the biscuits. "You share too?" "If you like." "Mitaki Lahi," he said, smiling. He pointed to the cheese. "That good with bread. I like it."

As we pooled our food and started to eat, he held up a cabin bread biscuit. "Only good for one thing Kapisiga." "What's that?" "Make good brew. I show you sometime - eh?" "Too right," I said.

The area I worked on was sown after a month of whisking up black dust which resulted in me taking samples back to the shower each night, although I brushed off what I could with a piece of rag. But a lot of it was glued to my skin by the flow of sweat the heat drew from my pores. By this time, the tan I had acquired in the cooler climate of the Mangaroa Valley, back home, had darkened to a deep olive, and I was wondering if my daily application of volcanic residue was changing the pigment of my skin.

It was Trevor who decided to change the trend of hairstyles on the island. He came up from the cowbails one night to take a shower, and while a few of us were sluicing ourselves, he said, "I'm getting all my hair cut off." "What hair?" Lex, the meteorologist commented. "You haven't got much now." "It'll help me beat the urge to leave before my time's up," he said. Trevor was already missing the bright lights of Auckland. And though he was getting his share of the local brew - he was unsettled. "I'll bet you don't have it cut," Cooky, the radio operator said. "How much?" Trevor asked. "Coupla bottles of beer when the next ship arrives." "You're on," Trevor replied. At the time I was thinking of the daily conglomeration in my own hair, even though I wore a cap. "I think I'll get mine cut off too," I said, applying a towel to my tingling body. Cooky gave his broad good natured grin. "You're on too." "Okay," I replied.

Mac, the Niue farmhand, who along with a couple of the other boys was deft with scissors, was chosen to operate on our scalps. There was a small audience present that morning; Charlie, a Norwegian, who was the rigger, flying fox operator and carpenter; Jimmy, the citrus fruit orchardist; George, the Postmaster and radio station chief; Reg, with his becoming smirk and Cooky, who leant over the verandah rail, nursing a hangover from a mysterious drinking session the night before.

Trevor wanted to toss to see who was to be shorn first. But as he had suggested the idea, we reminded him that he was honour bound to perform. It wasn't long before he was as bald as an eggshell. The pressure was put on me then, so I had no option. Then we were the victims of jeering laughter; we were only dressed in shorts, so with our deep tan and vivid white scalps we looked like a couple of gnomes or clowns without makeup. And Cooky, ill as he was, took a photo of us sitting on the verandah steps grinning like Cheshire cats. An hour later I passed Sammy, a Niuean, who greeted me. "Fakalofa Lahi Atu - Fifi Akoi?" "Mitaki Lahi," I replied, lifting my hat, and his eyes goggled as if they were on springs. The 'New Golden Hind' arrived a couple of weeks later, bringing in the new mechanic, Ron, Ben a handyman, Tom the cook and a soil surveyor, who was to stay for a few days while the ship sailed to Niue and back.

It was all available hands on Fishing Rock when a ship arrived. My job was to operate the homemade crane; a manual slew machine set on rail bogies, powered by a National one cylinder diesel engine and a Ford gearbox. It was lowered down a ramp from a shed forty feet above sea level. This was because of the violent seas that often broke over the rock. When loading was over, it was a bit of a pantomime getting the crane back up the steep slop. Chocks were used as a safety measure behind the wheels as the shed's hand winch snail crawled it up the ramp. (Twelve months after left the island, the crane managed, somehow, to get away and finish up in the sea.)

With the crane attached to swivel clamps, shackled to lugs in the rock to stop it from tipping, it was a matter of cranking the motor while balanced on a steel frame, often suspended over the sea. Not being the best of swimmers, I was a bit dubious - and I had visions of taking a dive, to be swept up on the sharp rocks nearby; but I eventually got used to it.

Dinghies were used to unload the ships that arrived, and when they made their first approach to Fishing Rock, a kedge anchor was dropped about fifty feet our, then a line was thrown ashore to be lashed to a ringbolt on the rock. This held the craft fore and aft. And when discharging started, a rope was secured to the top of the crane's wooden jib, and pulled by two men to slew it where required.

With the unloading of the 'Hind' over, life settled back to routine. But the advent of the arrivals and news from home affected Trevor. The nightlife of Auckland was beckoning, so he told Reg he wanted out, bald head and all, when the 'Hind' returned. Joe, the big, black bearded cook was due to go. This could have been the reason for Trevor's itchy feet - they had become drinking partners. I was sorry Trevor was leaving, he was a likeable happy-golucky bloke, who had worked on the Auckland waterfront and had done quite a bit of boxing by the look of his nose. Anyhow, he had decided to be the vanguard for Joe's return- to arrange the necessary female companionship required after twelve months in isolation.

We lived on the best of food, there was mutton, pork, fowl, the occasional turkey, fresh eggs, and fish when someone had a good catch - groper, snapper and blue cod were plentiful offshore. All the vegetables came from a garden kept in excellent condition by smiling Bill the farm hand - who never swore - and was often the victim of jibing. It didn't worry him.

More dust flew, road maintenance continued and a series of weather reports were transmitted before the 'Hind' did another trip from Auckland, and, at the same time H.M.N.Z.S. 'Kiwi' arrived with a film unit.

It was just over a month since Trevor's departure, and there was a stubble of green on the area that Hoppy and I, along with Reg's omnipotent urging had sown. Growth was quick in those sub-tropical conditions - my head was a mass of bristles - and I had the nickname of 'Leprechaun.'

There was increased activity at the Rock. The 'Hind' brought a broadcasting reviewer to do a colourful report of Raoul and Niue, and this brought about in the island's first air mail dispatch. A technician took ill with stricture of the bladder, and a Catalina flying boat landed in choppy seas. The brief dialogue between the radio station and the Catalina added to a tense situation. Station - "Have you landed yet?" Catalina - "Yes, several times, it's a bit choppy out here."

The sea was running fairly high that day, and it wasn't supposed to improve. So the aircraft left as soon as it could. Some hurried letters written - but as I had to stand by with the crane, I never had a chance to send an air letter from that volcanic heap of rock. Anyhow, the films were taken, the narrative recorded and the ships sailed - leaving us to our chorus of wind, sea and silence, along with the isolation.

We continued breaking in the land, disposed of buffalo grass with blade and disc, and Reg's guiding hand. By this time, Hoppy and I had a mutual understanding - especially as I had been his guest at home brew sessions with his mates, Mac and Kimani, Vakatama, Silitoe, and Viliamu. Reg persisted in waving to guide me as I pushed the conglomerate of boulders over the one hundred and fifty foot cliff to the beach below - but when I started to look on the opposite side of the machine, he gave up his hand signals. Nothing annoys an operator more than being shown where the safety edge of a drop lies - it's more nerve wrecking than judging it yourself. I often wonder if he ever saw Hoppy standing behind him mimicking his actions.

When the 'Hind' turned up for the third time, another Bill, an agricultural student from Massey University, arrived as farm manager. This time the ships stay was a short one. After it had left and we were congregated around the hostel table for the midday meal, Reg loudly announced - "Thank God there's no ships for two months. We might be able to get a bit of work done around the place now - ho - ho - ho."

Everyone exchanged glances. We were wondering if we had done nothing in the three months that had passed. George, the postmaster was the first to deflate Reg's balloon, by saying: "That's a good scheme, I think I'll start with a game of billiards. Any opponents?" "Yeah, I'll have a game," Cooky said, rising. Then Ron stood up, leaned his lanky frame towards Reg and asked, "And what do you think we'll do in our spare time?" Reg coughed and wiped his chin with a hankerchief. "Oh, we'll find something." Tom, who had been listening in the kitchen, poked his head through the slide. "Well I've got a bloody good brew bottled up, old chap. So I'll know what to do, won't I?" Charlie, gave his usual introduction to anything he was going to say. "Vaal you know - I tink I'll take a breath of :fresh air." Jimmy, who along with Charlie, had spent a few years on the island, stretched his arms and yawned. "Aah - I think I'll join you mate." And they ambled towards the gauze door to the verandah. Charlie, short and squat, Jimmy, tall and wiry. They were inseparable those two - and when they weren't working, they usually sat in two armchairs at the back of the hostel.

When we were working on Bell's Flat, we'd often go home for our midday meals. And afterwards I'd meet Hoppy at the entrance of the Niue camp and walk back to the flat with him. When the oranges were ripe, we'd put a few in our shirts as we passed the trees, then sit down and eat them when we reached the tractor - they were better in our stomachs than rotting in the soil as many did.

One day, Hoppy said, "You come to our camp on Saturday night?" He pointed to the oranges, "We got plenty brew." "Yeah, I'll be down," I replied, appreciating his invitation. The boys were cautious who they invited. Anyone they thought would inform Reg, was out. And when I recollect, everyone - except for a couple who didn't drink, at some time, felt the exhilarating effects of the brew. Many a night, there would be a tap on the gauze mesh on our bedroom windows, and when we opened the~ a voice would say, "Some brew Kapisiga?" This would be in return for bottles of beer we gave them after a ship had been.

Any time we sat talking, Hoppy would ask me about New Zealand. The island was a stepping stone to Auckland for the Niue boys and their behaviour determined whether they would be suitable to go to the mainland. This was good in some ways - but it had its anomalies. One ambition most of them had, when they went home for a holiday, or finished their term was to take a bike. But on the wages they received - it required a lot of saving. They were getting as much a day as we received an hour - five shillings. How could they cope with a strange environment, and a society which moved too fast to care for people who had been so close to nature.

I offered Hoppy my tobacco pouch. "Roll a few to keep you going mate.” "Thanks." "Who else is going on Saturday?" I asked. "Oh, maybe Lex or Cooky." "I don't think Cooky's on duty," I remarked. Someone was on all night at the radio station, in case of emergency, also to transmit weather information. "S' good," Hoppy said, then pointed, "Reg coming."

We could see Reg, but he couldn't see us. With his walking stick swinging rhythmically, he skirted a fringe of arums before the rise which would bring us into his view. "I'd better make a noise," I said, moving towards the tractor to step on a track cleat and slide onto the seat. I had the machine parked behind a clump of Ngaio, with the blade full of buffalo grass. The soft powdery soil sent up a cloud of dust as the machine moved forward and the grass rolled under the blade to make the machine lurch. I forced the blade down and kept it full as I headed towards the cliff's edge, determined to get rid of the load before Reg started any arm waving antics.

It's surprising the number of men you can get in a hut, but there were seventeen of us in one hut that night. It was someone's birthday, but it was celebrated with the hospitality it deserved. There was orange brew and bisquit, which was pronounced biskwee. The bisquit was made in a kerosene tin with a sediment of cabin bread, starch sugar and hops, and sometimes it was milky or clear depending on the ingredients available.

There were boys strumming on their coconut shell ukuleles, also a guitar; it was a wonder the singing didn't bring Reg storming into camp to end proceedings. As the night aged, the door opened and we sitting outside on the grass or boxes - and everyone was happy. I don't recollect ever hearing a harsh work at one of those sessions.

That was one night I remember more than any of the others. Lex had to leave early, and when Cooky and I managed to drag ourselves away, the dawn breeze was puffing - even though it was still dark. We staggered across the fill on the ravine - mumbling to one another. And when I turned to speak to Cooky, there was no sign of him. "Hey," I called. "Where the hell are yuh?" "Over here," came the muffled reply, then laughter. I went back to find Cooky sitting in a four foot hole that had been scoured out of the road's edge by recent rain -he had walked into it. There was an inquiry by Reg at the breakfast table about the early morning mirth. Someone suggested it could have been the mutton birds. But they had headed south some time before. Anyhow, if our laughter sounded like them - we must have been in the soprano range - mutton birds wail like babies.

Many a night our sleep was disturbed by earthquakes. These were usually preceded by loud rumbling, as if the crater was due to blow. Everyone tried to brush the idea from their minds, but it was often felt that the force of the shakes would eventually send the hostel plunging into the Pacific - it was only a hundred yards from the cliff's edge. Just before one occurred, I had a dream that prehistoric monsters were scrambling from the crater and stampeding across the island to leap into the sea. That was bad enough, but the shaking that took place as I woke made me wonder if it was really happening. It was that quake which brought down two slips on the Boat Cove road. And with the 'Pukaki' due to bring stores, they had to be cleared immediately. It took nearly three days to dispose of them with the dozer. A few trees had been brought down, and they created a tangle which slowed progress. Most of the rubble had to be pushed into a steep gully, but quite a bit of rock came in handy for improving that section of the road and a sharp bend which scoured badly with heavy rain.

With the 'Pukaki' were three other frigates, 'Kanieri,' 'Taupo,’ and 'Hawea’, and they hove to in the calm roadstead while the discharge took place. A day later they were gone - our last ships for a few months. We were again set to concentrate on the land development. All of Bell’s Flat was to be fenced along the cliff’s edge and in sections across to the road to provide alternate grazing paddocks.

In preparation for this, I worked with Bill, the farm manager, for a couple of weeks after Reg's midday pep talk. Bill taught me to split lengths of Ngaio into posts and batons. He was a pleasant fellow to be with; never hurried anything, but managed to get through a lot in a day. By the time we had finished cutting suitable trees into lengths with crosscut saw, mallet and wedge, we had a good supply for when the fencing started.

Two days after the frigates left, I was harrowing on Bell Flat, while Hoppy and some of the other boys started work clearing scrub for a proposed pipeline at Low Flat. As I did a circuit of the area, I noticed that Bill was urging a sheep towards a pen he had made at the foot of Pukemiro Bluff. The sheep had different ideas. As I swung the tractor around a clump of trees, it charged past with Bill in pursuit and headed over the cliff's edge. Bill took a brief look down then waved to me. I jumped off the machine to join him. He grinned. "That stupid, bloody ewe's gone over the side." "What were you chasing it for?" I asked. "It's got a fly blow. I'll have to dock it." He rubbed his chin. "Aah - tell you what. If you wait here, I'll shoo the thing up, and you can grab it when it gets in the long grass." "Okay." The wide verge of stubbly buffalo grass would make it hard for the sheep to get away in a hurry, so I waited. After about three minutes, I called. "Hey - what are yuh doing Bill?" "Over here" was the reply. I went to the edge, then gaped when I saw the position he was in it wasn't meant for anyone's comfort. He was down about fifteen to twenty feet, perched underneath the sheep. Behind him was a steep slope then a sheer drop of over a hundred feet to the beach.

"Christ," I exclaimed. "What are you up to?" "I can't move," he replied. I could understand that, he had nowhere to go - there weren't any ledges beside him, and nothing to grab above except the ewe. That was all between him and eternity. I moved slowly towards him trying not to dislodge any loose stones, then slithered over the few remaining tufts of grass until I struck a narrow ledge about four feet above the sheep. "Try and grab the ewe," Bill stammered.

With my heart pounding, I knelt on what felt like next to nothing, to grasp sparse tufts. When I leant towards the sheep, I found that I was about eighteen inches short, and if I let go, I would be on a point of balance that had no advantage at all. If I made any sudden moves I'd disturb the sheep. I eased onto my back and said, "Bill - I'm going to lower my left leg - try and grab it." He nodded, and if he felt himself sliding, he never had a chance to tell me - it all happened too fast. He reeled back, the sheep lurched forward, and I dug my feet and hands into the slope as stones rattled around me. Then I seemed to lie poised as Bill rolled over - bouncing on the cliff face a few times before he disappeared over an overhang with the ewe following.

If ever anyone felt they had arrived at the loneliest place on Earth- I did. I just couldn't believe what I'd seen. A few stones rolled past - then there was silence - except for the pulsating hiss of the sea. And peering down - I knew that all I had to do was relax and I'd be taking off into a blue void. My throat felt as if it had come into contact with a blast furnace and though my body had no feeling, there were rivulets of sweat dribbling off my brow to join others on my bare chest. The silence was invaded by what sounded like the roar of floodgate, and for a few seconds I pictured the mill stream at home. It just meandered through a gorge if it was in a serene mood; we used to catch eels in it - or lift stones to grab baby lobsters and cook them in a twig fire. When the rain gave the stream muscle, it stampeded through a series of steel plates onto drop structure, sucking weeds - or tossing logs aside like matchsticks - and it would fascinate us kids as we sprawled under the pines on the hill above - imagining what would happen if we landed amongst its rippling sinews.

I was suddenly sliding forward and I tensed. The heel of a boot hooked against a stone and I edged back - concentrating on the thin line where the horizon's two shades of blue met - as if it would suddenly lash out to draw me forward. My hands groped under my rump to ease me up, crablike, until I felt tufts pinch my skin. It wasn't until I was about a body's length from the top that I turned sideways to clutch at thick stubble and crawl the rest of the way. I stood at the edge trembling - my legs feeling as if they started at the knee caps. Then I looked down, trying to equate the present with what seemed hours before. I had a replay of Bill's tumbling flight; and breath grated through my lunge like sand against glass. From where I was I glimpsed the beach's array of craggy rocks and I closed my eyes as I visualized Bill's body mutilated by one, or crushed between the vice shaped clefts of boulders, or, maybe, he had been spared that - and the sea had taken him.

It was about two miles to the radio station, and when I started to move, I felt as if I was running across a field of wet concrete. It wasn't until I reached an orange tree against the Pukemiro slopes, that I managed to get into a rhythmical gait. My breath came heavy - I'd had no need to run since I'd been island. Our exercise was casual - a game of tennis or cricket - the odd plunge into the sea, or a day's trek to Denham Bay on the southern side.

As my pace increased - so did my thoughts - Bill could be suffering - dead - drowned - or even hanging from the cliff on something. My head throbbed - it was hell of a hot. I was going to change direction - make a bee-line towards the Norfolks then swing towards the cutting from the Niue camp. But something kept me on the track against the hill - maybe I thought I had a chance of seeing someone.

The sun seemed to be lapping my body with tepid waves as sweat oozed from its pores - then there was a cool bath as I passed under a canopy of Nikau palms beside the ever-damp arums. Everything was blurred, even though my steps were faster. I felt that I was on a treadmill - running but not progressing - the Norfolks away to my left were ominously outlined against the shimmering water and clear sky - like steeples of doom. Charlie Parker was buried somewhere beside them- he had died of tetanus. Bill might join him.

As I moved downhill, I could hear voices - and for a moment I thought the drone in my eardrums was fooling me - and then temporary relief - I had arrived at the taro patch. The boys were singing and calling out to one another. I seemed to float the last few yards and flop over the top wire of fence. "Hey, Kapisiga," someone called. "Whatsa matter?" Villiamu, the head boy asked.

My face must have projected my distress. There was a bottle of water near the fence. I lifted it and took a swig, then coughed out a mouthful as I gasped "It's Bill- Bill- he's fallen over the cliff." They were open mouthed as I continued. "Might need some water down there." I croaked in a couple of breaths and pointed. "Radio station, going to Radio station." My arm beckoned as I lifted myself to continue.

Their chattering became a buzz as my feet jarred my body, I had a good half mile to go and though I leant forward, my legs seemed reluctant to follow, but urgency drove me on. Every second wasted could be fatal.

As I crossed the fill over Bell's Ravine, I looked up the slope through the cutting and wondered how I was going to make it - my chest felt perforated, it was rasping so much. I wasn't fit - yet at home I'd run for miles training for sport. I began to wonder if a couple of miles were going to beat me. I forced deep draughts of oxygen into my lungs as I started on the grade - there were voices behind me but I didn't look around. I thought if I did, I'd flop down gasping and give in.

The station was in sight as I emerged from the sandstone cutting, but every step seemed just an inch closer - as if the buildings were moving away. But with only a hundred yards to go, I swung through the station gate feeling that I must have struck a second wind - my breathing appeared easier.

I pushed the gauze door and lurched into the room. Johnny looked around from something he was writing on a desk beside the radio equipment.

"What's wrong with you?" he asked. My mouth opened and shut - my voice box was locked. I licked my lips and gulped out the words. "Bill's over- over the cliff - fallen." "Eh?" Johnny exclaimed. George walked in from the other room. "What's up?" Johnny pointed. "He says Bill's fallen over the cliff." George puffed his cigarette. "Is - is that right?" "Yeah - yeah," I panted, "down the end of the flat." "Oh dear," George murmured, "poor chap. We'd better get down there."

My raw nerves couldn't keep still. "I'm going to let the others know." I rushed from the building, refreshed from the brief pause, and possibly a bit relieved that I had done a part of my duty. But then what could a radio message do at that moment? Maybe a Catalina would be there in a few hours; but the thing was the present - to get Bill, if he was alive, in condition for a quick exit from the island. I jogged past the cow bails, then as I reached the workshop I saw Jim.

"What's the hurry?" he asked. I told him and he wrung his hands together. "Oh the poor fellow - poor Bill." Ron's tall frame appeared in the wide workshop doorway. "Hullo - hullo - hullo," he beamed. Jimmy turned towards him. "Bill's had an accident. "Eh - what - where?" "He's had a bad fall." "Where?" "The cliff at Bell's Flat." "Down near Shifting Beach?" "Yeah." "Hell - Christ," Ron exclaimed, "We're going to have to get moving." "Where's Reg?" I asked. "At the hostel," Jimmy replied. I charged off as the boys arrived, and Ron called to the fellow who worked with him. "Hey Kimani. Come here mate." The hostel was only a stone's throw away, and although I felt exhausted - everything seemed lighter - the pounding in my ears had reached a consistent drone, but I ignored it as I rushed up the verandah steps to Reg's room. I could see him through the gauze. "Hey Reg," I gasped. "Yes," he said, pouting his lips as he opened the door. "What's the trouble?" "We've got to get down the beach," I replied, "it's Bill, he's had a bad fall." "Where?" I told him, suddenly feeling hot and cold needles piercing my body. "Oh - oh," he exclaimed. "Yes - where's everyone?" "Some are by the workshop." "Oh - I'll get my hat."

I rushed to my room to get my shirt. Then I took a short cut through the kitchen and headed for the workshop. Just about everyone was there. The full complement at the time was fourteen Niueans and fourteen palagis. A quick decision. We all started for the beach. Ron urged me to stay behind after all the rushing around I had done; but Bill was my main concern. I was just as interested as anyone else in his condition. We scrambled down a gully by the ravine, not far from the radio station. Most of it was covered with buffalo grass, so it provided good footing except for the odd patch of loose rock. Once we were on the beach, we half ran, half walked, scrambled over boulders; and rushed across wet, sandy stretches to beat incoming waves. Eventually, we were spread out and conversation lapsed. It was obvious as we drew near to where Bill had fallen that everyone was wondering what we would find. I think Bill was lucky that the sea was reasonably calm, and the tide was out when the accident occurred. We had just skirted a rocky area when we found him.

Bill had hit the edge of a six foot shelf of sand formed by heavy seas. It had broken his fall - and probably saved his life. He was dazed but able to speak. What a pitiful sight. Good natured Bill - he had nearly all the skin torn off his back, a shoulder was twisted, his eyes were puffed and practically closed and front teeth were missing. And I thought I was swallowing a football when he muttered through spongy lips - "I can't move - that bloody sheep." We checked to see if we could move him. Then a few of us removed shirts, wrapped around our waists, and tied them to thin branches to make an improvised stretcher.

Later, when Bill was as comfortable as possible, in the sick bay at the back of the hostel, radio calls were made to Auckland so Johnny could administer First Aid. Also, messages were sent to the frigates, because the rising sea ruled out the use of a Catalina. A period of gloom gripped us while we waited for the return of the 'Pukaki.' And when it arrived, the sea was up to it's old tricks, so she hove to in a heavy swell off the Rock. This prompted the captain to use a wise method of supplying medical aid. A motor boat towed in a whaler, which it released as it swept towards the Rock to drop the kedge anchor and throw the line ashore. The whaler, sharp at both ends and powered by five men with Indian paddles, maneuvered through heavy surf to briefly tie up while the doctor and sick bay attendant were transferred ashore in the crane basket.

Bill's departure was delayed the following day by the high seas. Giant white horses careered shorewards. So it wasn't until late afternoon, after radio consultation between the doctor and captain that a decision was made to get Bill away. Accompanied by the doctor and attendant, he was transported on the tray of the truck. It crawled the three miles along Low Flat and the winding heights above Oneraki Beach to the winch house.

We had the crane ready on its platform. This was awash, as waves romped ashore - lifting their cascading skirts over the surrounding rocks as they hissed like furies from a Greek tragedy. We waited, our attention divided by the sea, which we hoped would settle - the winch house - and the telephone ring to tell us Bill was coming down. The doctor, attendant and Johnny, with a walkie talkie strapped to his shoulder, rode down the flying fox on the tray with Bill. He strapped in a straight jacket stretcher and heavily sedated. As the tray poised above the Rock, Johnny sent a message to the radio station and this was relayed to the ship.

A motor boat hove to and was lashed to the kedge anchor with its motor idling, while another circled not far away. The doctor and attendant stepped from the basket into the rescue boat, then as the stretcher was slung to the crane's hook and I started to lift it, a wave doused my back. The rope on the jib tightened to slew over the bobbing craft. And as Bill hung above the sea, and the line dangling from the stretcher was grasped by the attendant, another wave cascaded over the rock showering the rescue party. I lowered him then the sea went flat and remained that way, until he was heading towards the frigate.

It took a few days for us to get over Bill's accident, but the dreamy atmosphere eventually returned. Even though it was mid-winter on the mainland - we were still wearing shorts and often sweltering with heat and humidity; and there was so much to be done. Reg had plans to keep us all occupied so we wouldn't succumb to the boredom. When I think of it now, what a beautiful isolation it was - away from the rush and frenzy of civilised society. Every day was like a Sunday - whether the sea was up or down, the weather calm or boisterous. There were variations of moods, sometimes a little friction, but nothing worth a mention in that paradise. It only had one fault, the lack of women; and this was possibly the core of certain tensions.

We finished breaking in Bell Flat and fenced it along the cliff's edge. Ben, Jimmy and I along with the Niue fellows all had spells of it. Pasture was encouraged on Low Flat with the aid of a plough that had seen better days. We gorged ourselves with oranges, grapefruit, watermelon and bananas and drank gallons of brew. Then, for some unknown reason, Reg withheld the rum issue, so we made inroads into a supply of passion fruit wine, which he had stored in the reefer room. It was humorous watching his startled expressions when we'd arrive at a meal, full of 'fong', as it was known. I think he realised at a later date, when he found his jars of wine had turned to water.

Johnny Wray, who had frequently visited the island with his ketch 'Ngataki' when Alf Bacon, a Sunday Island Pioneer, was in residence, paid us a surprise visit. He appeared one morning off Fishing Rock and as there was no means of communication with him, Ron, the mechanic, decided to swim the shark infested mile to board the new ketch 'Waihape.’ This resulted in Johnny coming ashore in the island's dinghy. His had been washed overboard and damaged off White Island during a storm. He was welcome, especially because he brought a supply of honeymead with him, so along with that and the appearance of some closely guarded rum, the hostel walls echoed with laughter.

There were the four mile trips to Denham Bay, the usual trekkers being Cooky, Lex, Johnny, Ron, Ben and I. Maybe it was because the surf inviting beach faced home, that we were drawn to it. Then after scrambling the steep, narrow tracks, we'd arrive back at the hostel famished. A feature of the visit was to see the Wideawake terns smothering the beach. It was wise when their thousands surrounded us, to move below their fluttering curtain with sticks held above our heads.

We invaded the crater, led by Villiamu, who was an expert bushman. In places we had to swing from tree to tree on the steep sloped to maintain progress. There was an eerie atmosphere in that volcanic tinder box. The shore of Green Lake was just a mass of transparent forms of dead locusts which had apparently been overcome by the pervading sulphur fumes. We negotiated a plateau to reach Tui Lake, a black pool surrounded by palms and ferns. It was supposed to be bottomless - and maybe it was - no water could be so dark and shallow.

We scrambled our way through guardian clusters of pohutukawa that were so thick only a pale green light penetrated to the forest floor, as if to deter intruders from the throne of fumeroles, a ridge overlooking a broad area of the crater. From there we wondered by what miracle we had arrived, and how we were going to get back. The bush was so vast. The fumeroles exhaled periodic puffs of steam, as if they were snorting with knowledgeable delight because the source of their misty ejaculations had power greater than any known by man. The atmosphere seemed tense and even the birds shunned the area.

The months spread their wings and flew towards December, when we'd be going home. We started counting the days. Bell's Flat, was a pastoral masterpiece - there was a new pipeline running from the pumping station at Blue Lake. Our trips to various parts of the island increased as if every free day we had would never happen again. We went along boulder strewn Shifting Beach to Hutchison's Bluff - around the rim of the crater, from 'Number One,’ a second World War army lookout on Pukemiro Hill, to where it coincided with Boat Cove Road. We nearly got lost in the attempt - managing to get out of the bush just before nightfall.

But Denham Bay was the popular spot. We'd lay on the beach sometimes oblivious of the Wideawakes hovering above, staring South towards home, wondering what civilisation was doing. Now I wonder if our concern about the industrial comedy of errors was worthwhile. Isolation may have bugged us at times, but maybe we didn't realise how well off we were.

H.M.N.Z.S. 'Rotoiti' arrived in December, bringing a full complement to replace all the 'palagis' except Tom, the cook. And the manning the ship arrived, we basked in the sun on Fishing Rock, watching the laden long boat laying a path of sparkling foam on the lazy blue swell.

A Petty Officer's whistle blew for AB's to lower boat hooks to lift the kedge anchor line - then another blast to make it fast to bollards fore and aft. The basket swung over raised hands - eager to grab it and get it down. The first man to step on to the rock was Bill, with his broad, good natured grin - flashing gold in the front teeth that had been shattered by his fall. It was good to see him - he was a brave man - coming back to face an isolated period of life, where he had nearly lost it for the sake of an animal.

A week later it was our turn to clamber into the basket. There were farewells from the Niue boys who were staying to qualify for entry to the Palagi big smoke. And though they didn’t show it, they must have felt some form of regret as they sang and waved to us. They had presented us with lava lavas, vakatamas and ukuleles made from coconuts. They, like us, would be left with memories.

As the 'Rotoiti' vibrated into 'full ahead,' and glided West, I stood aft, along with a few others, until we "rounded the corner" at Hutchison's Bluff - the pines disappeared and so did a long Sunday. I can still see the pines - hear the songs of the Niue boys - the screech of mutton birds - wideawakes - the Pacific's thundering roll, or its sorrowful hush. The thing that remains with me is the serenity of it all - peace is hard to forget.

(Len Chambers was resident on Raoul Island in 1949 and has also served on the Association's committee recently. His story is a remarkably fine effort and the present committee thanks him for a lot of hard work. Needless to say perhaps, that although Len was there during the 'formative' period of the station's installation, even the most recent returnee will have no difficulty in slipping into the slot and feeling the true atmosphere the tale generates. For the 'old timer' whose memory may have slipped, Len adds a footnote of explanation for some of those more exotic words: Kapisiga - friend Kelea - no good Mitaki Lahi - very good Vele Lahi -very hot Palagi - white man Fakalofa Lahi Atu, Fifi Akoi? Very good morning, how are you? Lava Lavas - long floral skirts Vakatamas - miniature catamarans The Editor.)

**************************

FILM EVENING ….FILM EVENING

Don't forget the Annual Film Evening on Saturday night, the 22nd of June at 8pm. Admission is free and we have gathered some excellent films together. Full members are requested to roll up at 7.30 to vote on an amendment to the Constitution, see page 223. Full details of the evening will appear in the June issue of 'The Islander.'

*********************

Familiar Faces: from the 1964/65 Campbell Island Expedition. Left to Right, 'Kip' Kipplewhite (Ion), Mike Criglington (Met), Alan Guard (Mech), Peggy, and Warwick Fergusson (Tech), at a pegged nesting site of a Rotal Albatrodd. (photo: Colin Clark)

Familiar Faces: from the 1964/65 Campbell Island Expedition. Left to Right, 'Kip' Kipplewhite (Ion), Mike Criglington (Met), Alan Guard (Mech), Peggy, and Warwick Fergusson (Tech), at a pegged nesting site of a Rotal Albatrodd. (photo: Colin Clark)

*********************

THE ISLANDS REPORT IN

Campbell Island

As this is being written mid-January, the usual activity for this time of the year is going on, namely that of stock take and stock orders being prepared, and no doubt previous OIC's will remember the large amount of hunt and check on the keyboard that this involves, although to give credit where credit is due, our mutual friend back in Administration had produced some excellent photocopied sheets for this purpose, but - oh, why wasn't there a set for all the powerhouse - part number, type, stock, etc.

December brought its fair share of visitors, with the 'Tangaroa’ putting in on the 13th for repairs. The visitors who came ashore were entertained in the usual Campbell Island style, and it was nice to have a little female company in the lounge. This ship also gave us an excellent chance to get our own mail back to N.Z. in time for Christmas.

Following this we had a ship a day for 3 days running. First was the 'Glacier’ on the 23rd with some stores and mail, this latter of course, being the most welcomed item ashore. Next day the 'Satsu Maru 17' put in for the night, and the Kiwi skipper and four Kiwis on board her, came ashore for another memorable night and later on we were joined by the Japanese captain and some of the crew. The next day being Christmas Day, marked the arrival of the 'Lindblad Explorer' who dropped anchor at 9.15 am. Campbell Island weather behaved itself for a change and a very pleasant day and bright sunshine, was spent showing the tourists around the island. Afterwards we were all invited back on board for Christmas Dinner and a party with a dance afterwards. This was most enjoyable and with all the boys in good clothes, plus the odd tie or two in evidence they made a fine looking team. It was with extreme reluctance that we left at 10.30.

Our own Christmas Dinner took place the following Tuesday the 28th and Jim turned on an excellent spread for the night. A patrol Orion dropped us a container of newspapers on the 27th and tried again a week later, but high winds forced the abandonment of this second try. Around the camp a new road has been put in to the Met Store doorway, and the road to the bombshed has been extended.

On one of our fowl house cleanouts, the smell was so overpowering, our mechanic lost his top set of teeth into the harbour. Most distressing, however, 24 hours later, after shifting half the rocks in Perserverance Harbour they were found and restored to their proper position. The North West Bay hut had a period from the 4th January of almost continuous occupation and once again proved it's worth many times over as an excellent base from which to travel to all the bays on that side of the island. The usual large supply of philatelic mail came in at Christmas and the island has two new cachets, plus another per courtesy of Mr Lars Lindblad. So, no doubt once this information gets around there will be more large piles of letters to deal with.

Rex Firman.

_________

Raoul Island

At the time of writing we are only 4 weeks away from our half way mark. It seems like only a couple of weeks ago that we arrived. The first few weeks we did all the usual things that a new party does, like finding Denham Bay, Hutchinsons Bluff and Ring Buster Track (very aptly named so I’m told on very good authority). We still haven't found the cache of Scotch Whiskey which is reported to be at D’arcy Point. A wistful look comes over Swampy Crompton's face whenever the subject comes up.

Birthdays, Christmas and New Year's celebrations have come and gone. We have had another yacht visit us. This was the 'Maya’ which was at the end of a two year journey from the U.K. to N.Z. and stayed with us for two days. The folks on the 'Maya' said that the underwater fishing was the best they had found throughout their journey. Angus (the bull), the bastard, is still pushing his way through fences with scant regard for anybody who happens to stand in his way as was found out by one member of the party. However, Paul Stewart (farmer) has refortified the bull paddock and he's keeping his fingers crossed that this time he has Angus penned in. It wouldn't be so bad if Angus did something when he had company, but he doesn't despite loads of verbal encouragement and advice from party members on the touchline.

ONE OR TWO NAMELESS HIGHLIGHTS SO FAR: The nameless mechanic who came in for lunch one day said 'Good oh, pikelets’ and proceeded to smother his fish cake in strawberry jam and had eaten half of it before he realised. The nameless technician who one dinner time said 'That gravy looks good' and poured chocolate sauce over his roast pork. The nameless leader who misplaced the boat while transporting it from the hostel to the rock. He had gone about a quarter of a mile before he found the boat was no longer attached to the tractor. The nameless Snr Met who insisted on changing his usual grey feathers for a white sports shirt and caused 465mm of rain to fall in 23 days. He was duly exorcised. He had been warned not once but a 1000 times.

The boat has been used quite a lot when the weather has been suitable and quite good hauls of fish made. The record so far this year is a 54 pound groper. We had a slight mishap at Meyer one day when the boat was turned over on a rock and had to be rowed back home. Unfortunately, Dutchy den Haan (mechanic) lost his teeth and hasn't got a spare set with him. One item which has caused a fair amount of discussion is the record for the time taken to walk from the Denham Bay Hut to the Hostel. The record this year so far is 39 minutes but we would be pleased to hear from past Islanders who have made the perilous journey in less time than this, to enable us to set the record straight. You all know our phone No.

Contribution from the Chef: After the first few weeks of our sojourn on the island of desire the team began to organise itself into a routine. As cook my dreams of a peaceful idyllic existence were shattered about the fourth week as the kitchen renovations started to take shape. Masses of masonry, plasterboard and cockroaches were hurled indiscriminately, it seemed to me, on floor, food and faces. However, after many weeks of excruciating frustrations and numerous oaths, the happy cook received the handywork of the native tuis in revered awe. It was magnificent now - a monument of spotless white board and metal including brand new diesel fired stove and water heater.

The climate of Raoul is all we expected and then some although numerous bugs, caterpillars, flies, cockroaches, and ubiquitous rats make gardening a little difficult. We are told that February was the driest on record, but January was quite wet with one terrible day having over 6 inches of rain. This of course combined with a dry March bodes ill for the winter months. No one thought to bring water wings.

February saw the departure for N.Z. of our handyman, Gavin Robertson, and this must be a record for one of the shortest stays on the island. The ever generous M.O.T. has of course arranged for his salary to be divided amongst the remaining party members. The island has kept up with the usual shakes and rumbles. Our resident Mr Gloom has rigourously kept up with practising his breast stroke. In closing, the lads wish to join me in wishing all members of the Association a belated but prosperous New Year.

Geoff Charlton.

********************

Sorry about squashing up those Island articles, but I was fast running out of room and the printer doesn't like me to go over the page. Also apologies for being so late with this March edition, but I have just been through a most mixed up month or so. Regards, The Editor.

*********************