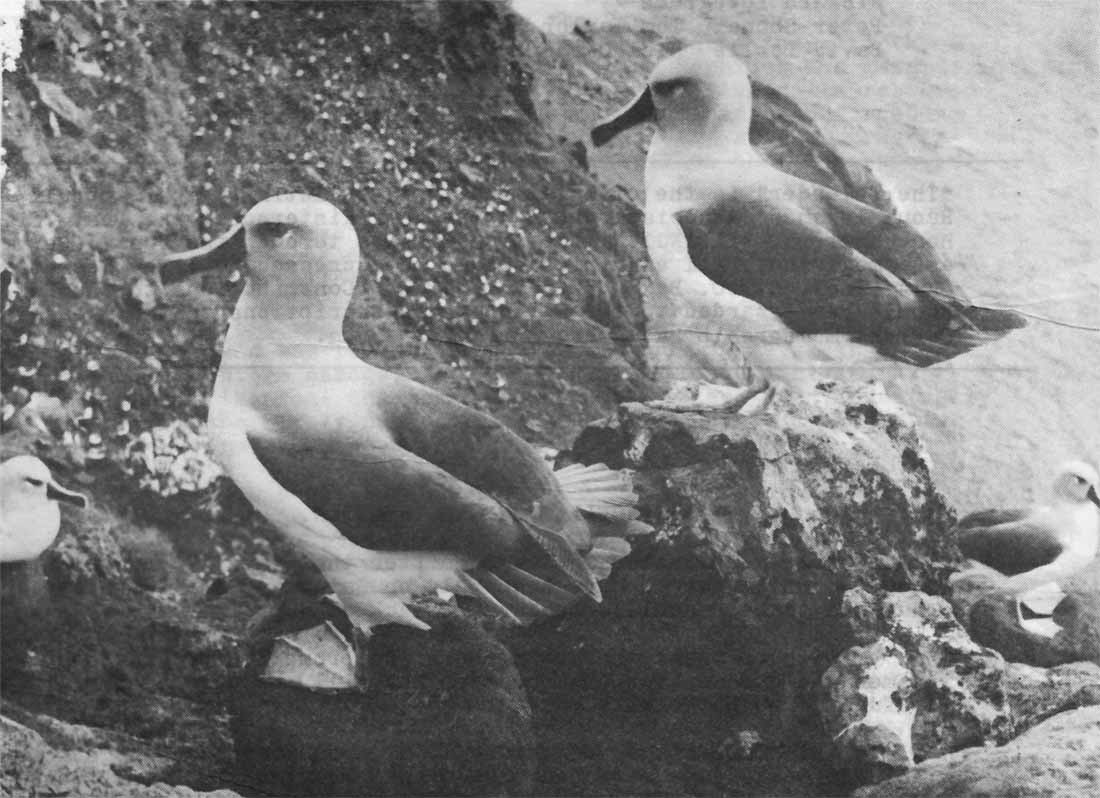

CAMPBELL RESIDENT: The grey Headed Mollymawk (Diomedea Chrysostoma) with its mauve head feathering and conspicuously yellow striped beak is one of the most beautiful of the small albatrosses. The photograph shows resident Mollymawks near the top of the cliffs at Courrejolles Peninsula. (photo: C Clark)

CAMPBELL-RAOUL ISLANDS' ASSOCIATION (INC.)

NEWSLETTER Vol 2 Number 12 SEPTEMBER 1974

Association Officers 1973 - 74

Patron

Air Vice-Marshall A. H. Marsh C.B.E.

President

Bernie Maguire

| Secretary | Treasurer | |

| Peter Ingram | Bill Hislop | |

| Committee | Honorary Members | |

| Richard Lovegrove | M. Butterton | |

| Peter Shone | H. Carter | |

| Tom Taylor | Capt. J. F. Holm | |

| David Leslie | I. Kerr | |

| Noel Caine | C. Taylor | |

| H. W. Hill |

Newletter Editor

Peter (Pierre) Ingram

"The Islander" is the official quarterly bulletin of the Campbell-Raoul Islands' Association (Inc.) and is registered at the Post Office Head quarters, WELLINGTON, for transmission through the Postal Services as a magazine. All enquiries should be addressed to: The Secretary, CRIA (Inc.), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON. Contributions to the bulletin should be forwarded to the Editor, CRIA (inc), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON, and subscriptions to the Treasurer. Current membership rates are $3 per annum.

____________

STOP PRESS:

CANCELLATION OF REUNION

It is deeply regretted by the commitee that the 1974 Association Reunion which was to have been held on Saturday 21st September, has had to be cancelled because of lack of support.

we wish to thank the few members who promptly forwarded their names and cheques for the occasion and will now receive immediate refund through the mail.

At this late stage, Wednesday 10th, a count shows only a possible 30 would have attended when 80 was required to break even.

The Annual General Meeting will still take place as advertised at 1.45pm on Saturday 21st September in the lecture hall of the N.Z. Meteorological Service's Head Office at Kelburn.

P. M. Ingram, Secretary

___________

Editorial: SAFETY AND THE HIGH SEAS

In the second week of June, the Tongan fishing vessel, 'Ata' was successful in locating the crew of the 38 foot sloop 'Sospanfach’, perching uncomfortably on the ocean swept reef of Middleton, 170 miles north of Lord Howe Island. The yacht had departed Auckland on April 7th, dodging marine authorities and Custom formalities, and had evidently tackled the Tasman with a single suit of sails, no auxiliary engine or radio, and a ‘badly set’ rudder. To the yacht's credit was its recent construction in ferro-concrete but no analysis of the skipper's behaviour and planning will ever determine a favourable balance.

lt is also of little credit to the Sunday papers that they took their usual tack in examining and expanding the slim theme of the discomfort of the two scantily clad heroines and general crew disharmony. So be it. The taxpayers of Australia restored the adventurers to the innocent parents that had been forced to suffer over a period of some six weeks and the skipper bravely announced that he would rebuild and be back on the high seas in the not too distant future.

So miraculous was the rescue, that the incident of the 30 foot sloop 'Moeroa’ in Raoul's Denham Bay on Sunday 9th June received scant notice.

The 'Moeroa' was a contestant in the Auckland-Rarotonga yacht race and was forced to divert to Raoul on May 29th after sustaining storm damage. Due to the condition of the sea at Raoul, the 'Moeroa' changed her anchorage three times, eventually selecting the highly dubious area of Denham Bay to await better conditions before proceeding North again.

The crew then elected to go ashore and cross the island to the hostel, so as to join in the normal Raoulian Saturday night capers which have proved so attractive to visitors over the years. Needless to say, the unattended 'Moeroa' slipped her moorings and was nowhere to be seen after the crew returned the following day. It was the New Zealand taxpayers' turn to cover the rescue which involved the diverting of the M.V. 'Lorena' to Raoul.

Because of localised interest, I have noticed some strong comments coming from Association members over the incident. Certainly the volcanic ash and rubble bottom of Denham Bay, coupled with the bay's shallow indentation which accepts every horizontal movement of the adjacent ocean, makes it one of the least desirable anchorages in the South Pacific.

Unfortunate and unofficial reprimand has also been placed on the officer in charge in permitting the full crew to remain in the hostel area while their craft was in such a dangerous position. The judgment on this latter point may well be unjust, as no one knows whether or not a warning to the skipper was ever passed. What appears to remain is a case of gross negligence on the part of entire crew and another expensive lesson learnt.

********************************

PETROL, PISTONS & PROPELLERS

Recently John Jerningham recorded within his Evening Post column, a pre-teen's excitement upon learning that he was to travel by NAC Friendship to Nelson. Why should such a common event raise the pulse rate in the lad? It was to be the first time he had ever travelled in an aircraft with a propeller. So time ticks.

Petrol, pistons and propellers have served well in the past, but in the commercial and defence sector, their use is drawing to a close and with it a unique and welcome service to our islands is also on the decline.

The Orions of Whenuapai thrive on a slightly different diet, and although they have the necessary flexibility of a propeller driven aircraft for supply dropping, the operating cost of such a sophisticated maritime aircraft, is such, that only the most urgent of missions can be accomplished.

There is no doubt that the visits of the RNZAF to both islands have proved highlights among expedition members in the past. The Sunderlands of Hobsonville's Maritime Operational Conversion Unit became so frequent a sight in the Kermadec skies during the '60s, that it was almost possible to follow Auckland's cinema changes. Station Warrant Officer Bert Haycock became the ‘get it man’, who only required one shopping day interval from receipt of the R/T message to time of dispatch. Books and newspapers collected from the various messes rained from the skies. I even saw a washing machine bowl go out the door of a 40 Squadron Hastings one day. Later that year when it was my turn to go to Raoul, I found out what it was for.

Without exception, there was always a humourous note in the 'drops by the boats.’ It might have been something found in the dropped supplies, a near, miss to some semi-valuable departmental object on the ground, or a bit of daring along the plateau if the wind conditions permitted. And there was always that brief air to ground comradeship even though only a white blur of faces could be seen throughout.

There have been the isolated occasions when the RNZAF has had to turn serious, weigh their chances and go - sometimes the odds being hopelessly in reverse. Such an incident is recorded in Geoff Bentley's recent book, 'RNZAF, A Short History', and I quote the relevant chapter in this issue of the bulletin, as it involves our Patron when he was D.M.S....

Flight Lieutenant Ewing, RNZAF's Public Relations Officer in Wellington, supplied the photographs that you see in the centre pages. So once again you have the shapes of the boats. With little memory you will also have the sounds. It was only a decade ago.

Pierre.

**********************************

MEMBERS COMMENT

Early in 1968, I lugged a massive (by today’s standards) tape recorder up the lift in a city building to interview Allan Henderson, then Chief Surveyor, Wellington District. The results appeared in Newsletter No 2, and the article told about his surveying years with the Kerrnadec Island Expedition in 1937 - 38. If you thumb through the Aeradio Report, you will notice that most of the photographs are his and I would think he easily classifies with Tom Bell and Alf Bacon when it comes to being a Kermadec Great. Because of the nature of his work, he also had an enormous technical knowledge of Raoul, so perhaps he really has no peer, and had he not been a Public Servant and thus permitted recognition, he may well have carried off the crown and become the King of the Kermadecs.

Anyway, I was very pleased to hear from Allan the other day and I quote from his first letter -

"I have got a lot of pleasure from (the last issue of the bulletin) and especially the photographs - though you did not get as far south as Esperance Rock. I must admit to putting a dirty smudge on it in 1945 with an aluminium marker from a Hudson - a bit of not so bad bombing in a low level run from the East. It is a long time since those days in 1937-38 when we did a bit of hard work on Raoul, and I have wanted ever since to go back and have a look round it, and especially at a lot of unfinished business there, and to collect a few items left planted in odd places. Time was too short to waste in the few months we were there to look into many strange and interesting things, or to have a good look over Napier, Nugent, Dayrell and the Chanter Islands and a better exploration of Meyer Island - and not forgetting the wreckage etc, (Columbia River, wrecked September 8, 1921, Ed.) on the South West Coast. I wonder if any of the chaps since have had the time and energy to have a good look at the whole South Coast and its relics, or along Hutchison Bluff beaches. There are so many interesting possibilities and old things which would be most interesting - with time and much energy - perhaps a lot easier with a good boat and a reliable outboard - our old 14 footer double ender was good but hardly sufficient and overmuch hard pulling. However, one has got a bit longer in the tooth, and a bit less energetic with time, and I do regret not being able to satisfy that wish to complete the job. But as the soiled urchin said while there's life, there's soap, and maybe I will get to see the old place again one of these days. I did enjoy the sight of it when I was with P.G. Taylor in Catalina JX275 - 'Frigate Bird' - in 1944."

The 'Frigate Bird' rang a distant bell in my memory, but I completely failed to locate anything about it in my notes. I therefore wrote back to Allan and received in turn a most full and interesting account, from which I have extracted the following - Catalina JX275 was temporarily attached to 45 Atlantic Transport Group with headquarters in Canada, for delivery to Coastal Command, but made available to P.G. Taylor (later Sir Gordon Taylor, G. C., M.C., author of 'Forgotten Island', 'The Sky Beyond', and 'Bird of the Islands.') for a South Pacific survey flight. Such a survey was requested to determine a delivery route free from icing for flying boats and bombers being diverted from the European theatre of war to the Western Pacific, as the former started to run down in 1944. The Catalina was subsequently flown to Bermuda for fitting out and was christened 'Frigate Bird'. At the time, Allan was Nagivation Officer (Bermuda) for the Transport Group.

They departed Bermuda on the 4th September, 1944, flying via Nassau - British Honduras - Acapulco - Clipperton Island - Bora Bora - Papaete - Aitutaki - Niue - Auckland (via the Kermadecs) to Sydney. They then returned through the central Pacific.

Overhead at Raoul from 2235 to 2246 hours (GMT) on the 26th October, Allan reported plus l3C with a wind vector of 135/12 at the 1900 foot flight level and he then gazed down on all those twisting contours he had surveyed with the KIE in 1937-38. Plodding on with an IAS of 103 knots, they visited Macauley, Curtis and Cheeseman, and finally L'Esperance.

Those of you still scratching your heads over P.G. Taylor, will probably recall now that he was copilot to Kingsford Smith in the Tasman crossing by the 'Southern Cross' in 1931, and was responsible for that heroic midair reoiling of the Fokker's overworked port engine.

_________________________

BEST WISHES: to all and a happy reunion were the kind thoughts of member Doctor Janet Brown in a recent letter to the Editor. Janet would have been with us on the 21st, but unfortunately sustained a back injury in a recent fall. However, she is up and about again, although the Auckland - Wellington trip this September would obviously have been a little much. So it is a 'get well soon' from all of us Janet and we will be thinking of you on the 21st. (Janet was recently A.M.O. to D.M.S. Tony Marsh and Guest of Honour at the 1971 Reunion. Part of her memorable dinner speech is recorded in 'The Islander' Vol 2, No l, a seasonal piece of reading with the 1974 Reunion so close at hand. Ed.)

BEST WISHES: also from member Dr Gordon McDougall, Principal Medical Officer to the Ministry of Transport. He will unfortunately have to attend an Aviation Medicine Conference in Rotorua over the Reunion date.

*****************************

CREW LOSES ALL IN STORM. Evening Post 10.6.74

Three men and two women from Auckland lost all their posessions when their 30ft sloop 'Moeroa' was battered to pieces on rocks at the foot of cliffs on Raoul Island. News of the loss came from a spokesman at the weather station at Raoul Island in a telephone interview from Christchurch yesterday. He said the yacht had taken part in the New Zealand to Rarotonga yacht race, but had struck bad weather and had called at the island to re pair damage and take on water before continuing a cruise of the Pacfic. Now the New Zealand Shipping Corporation ship 'Lorena' has been diverted to the island to pick the crew up. The 'Lorena' is due at Raoul early tomorrow and is expected back in Wellington on Sunday or Monday. The owner and skipper of the 'Moeroa’, Mr G. Treadgold, a 24 year old Auckland surveyor, took four years to build the yacht which was worth about $10,000. The crew stayed at the weather station on Saturday and next morning discovered the yacht had dragged its anchors and had been pounded to pieces in a storm overnight. Only a small portion of shattered decking was recovered. The crew are Miss Debbie Lee, 19, Miss Sharon Reid, 21, Mr Murray Williams, Mr Graeme Cornall and Mr Murray Waldbran. They were all from Auckland.

*******************************

ANGELS OF MERCY by Geoffrey Bentley.

'RNZAF, A Short History.' Publishers: A.H. Reed 1969. Extract Chap: 22

One morning in October 1951 the telephone rang in the office of Wing Commander A.H. (Tony) Marsh, Director of Medical Services at RNZAF Headquarters in Wellington. Mr T.P. Hammond, leader of the meteorological party on Campbell Island was seriously ill with an abscess in his neck.

Campbell Island, the most southerly of New Zealand's outlying islands, some 425 miles south-east of Bluff, is a desolate, gale-swept spot in the sub-Antarctic region, where a New Zealand weather station was established in 1940. If the Air Force was to help, a flying boat was the only means. In the right conditions, a flying boat could land at Perseverance Harbour - a narrow strip of water four miles long, flanked by peaks of up to 1,567 feet.

The DMS spoke with the Director of Operations and their proposal to use a Catalina flying boat from 5 Squadron in Fiji, was endorsed by Group Captain R.J. Cohen, then Deputy Chief of the Air Staff. For the Catalina's crew members, this meant a flight of 2,270 miles from the tropics to the sub-Antarctic in a bid to get Mr Hammond to hospital.

The Catalina squadron was tasked to deploy an aircraft from Lauthala Bay to Wellington, take Wing Commander Marsh on board, and then fly to Campbell Island. If necessary, the DMS would operate at the island; but in any case the patient would be brought out and taken to hospital in Invercargill, the Catalina landing at Bluff on the return flight.

Carrying two crews, the Catalina landed at Evans Bay, Wellington, on the afternoon of 5 October. They were shown a film of the island at the Miramar studios of the National Film Unit, and later, at the briefing, the men were warned that the weather would be bad.

At midnight, Flying Officer D.F. Clarke, DFC, the Catalina's captain, took off into the darkness, and Group Captain Cohen, having personally seen them off and wished them good luck, drove home to Pukerua Bay.

The "Cat" spent seventy tantalising minutes over Campbell Island without anyone sighting land. The island was in the centre of a series of rain-squalls which screened it from view. With hidden peaks reaching to nearly 1,900 feet, any approach in such conditions would be highly dangerous. "We've got to give it away, fellas," announced Doug Clarke, and he asked his navigator, Flight Sergeant D. Ballantine, for a course for Bluff.

In the galley, four dozen eggs, bacon and juicy steaks remained uneaten, a fault in an electric generator preventing the crew using their cooking facilities. About l pm a long struggle had been partly won and the engineer, Flight Sergeant L.G. Woods, and his assistant, Sergeant L.A. Wood, had produced cups of hot tea to fortify the weary crew, and at 2.22 pm the Catalina was skimming over Bluff Harbour.

But there was more work ahead. The aircraft had to be refueled and then serviced in preparation for another attempt. They got to their hotel for a meal at 7pm.

Meanwhile, at Campbell Island, Mr Hammond, who had not eaten for several days and was unable to sleep, was treating himself with Penicillin under radioed medical direction. In pre-penicillin days his position would have been much more serious.

At Bluff's Club Hotel the crew were up very early next morning and at 7 o'clock they were airborne on a flight that they were unlikely to forget. (Group Captain Cohen had said it would be a "dicey do." It was.)

This second attempt, also, was made in extremely hazardous weather. It was abandoned only when circumstances made it impossible of success. The crew had no difficulty in finding Campbell Island. They came on it after emerging from a rain squall at 12.36 pm. After circling the island another squall was encountered as it approached Perseverance Harbour. A sudden down-draught dropped the aircraft 400 feet, then up currents pushed it violently upwards at frightening speed.

Master Signaller K.T. Gatrell, of Marton, the radio operator and a veteran flying-boat crewman, had two ribs broken when he was flung to the floor of the aircraft. Wing Commander Marsh was dashed against the ceiling and then thrown across the rail of a bunk, severely bruising his chest and ribs. Flying Officer Clarke, though strapped in his captain's seat, had his shoulder badly wrenched in his stubborn battle to keep the plane under control. Also strapped in, Sergeant D. Winter, of Wellington, the co-pilot, had one hand gashed. Strapped in the engineer's tower, Sergeant Wood was unhurt.

The luckiest persons aboard were almost certainly Flight Sergeant Ballantine, Flight Sergeant Woods and Mr Duncan Campbell, an Evening Post reporter. They were in the gun-bay photographing the approaches to the harbour and had only just closed the perspex canopy, called the "blister" - when the aircraft fell and then was sucked wildly upwards. Seconds earlier the "bump" could have thrown one or more of them through the open hatch. As it was, they had a bad moment. Ballantine pitched to the floor, smashing his camera and Woods received a nasty cut below the knee as he was catapulted from the port to the starboard gun-bay.

A 50lb anchor in the Catalina's nose struck the ceiling and then dropped heavily, smashing the starboard catwalk to matchwood. Worse, the hydraulics operating the aircraft floats were put out of action, and the trimming gear was damaged.

For the second time Doug Clarke was forced to announce that they were "giving it away." They turned for home at 1.30 pm, the captain climbing to 11,000 feet to escape the worst of the turbulence. At 3.31 pm the Catalina was diverted to Evans Bay, Wellington, but this instruction was countermanded because of deteriorating weather. At 5.40 pm, the aircraft was down on Bluff Harbour, the floats having been manually lowered for a landing. The crew had been in the air for just on ten hours. A chagrined crew learned later that the Navy had sent HMNZS 'Kiwi' to take Mr Hammond off the island.

(Geoffrey Bentley rejoined the RNZAF in 1949 as Press Officer, later being appointed Director of Public Relations, retiring in l966 with the rank of Squadron Leader -Ed)

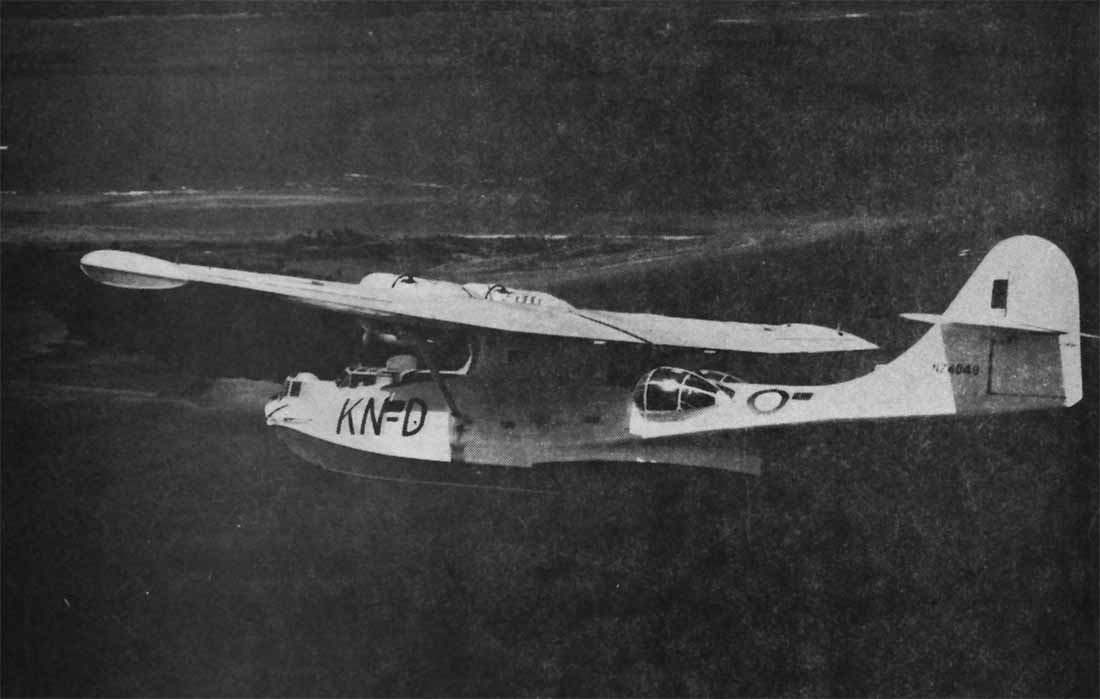

Consolidated Catalinas were phased out of the RNZAF on the arrival of the Sunderlands during the 50s. Flight endurance when with Coastal Command had been known to extend up to a phenomenal 30 hours. (Official RNZAF photo)

Consolidated Catalinas were phased out of the RNZAF on the arrival of the Sunderlands during the 50s. Flight endurance when with Coastal Command had been known to extend up to a phenomenal 30 hours. (Official RNZAF photo)

Short Sunderlands of RAF Coastal command, possibly 201 Squadron now equipped with the nimbler Nimrod, had little external difference to those used by the RNZAF. Supply dropping at Raoul normally conducted through the aft entrance forward of the fuselage roundel. Small packages usually were thrown from the taxing drogue hatches either side of the galley. (Official RNZAF photo)

Short Sunderlands of RAF Coastal command, possibly 201 Squadron now equipped with the nimbler Nimrod, had little external difference to those used by the RNZAF. Supply dropping at Raoul normally conducted through the aft entrance forward of the fuselage roundel. Small packages usually were thrown from the taxing drogue hatches either side of the galley. (Official RNZAF photo)

**************************

RECOMMENDED READING - WHO’D MARRY A DOCTOR

Elaine Grundy Whit. & Tombs 1968

Thirteen years had elapsed before Elaine Grundy decided to write ‘a Chatham Islands casebook' on her doctor husband's 1954 tour for the North Canterbury Hospital Board's most remote post. Her memory is undoubtedly brilliant and little has escaped her attention with the passing years Despite a somewhat sheltered and methodist upbringing in Christchurch, she also has displayed a strong ability to portray accurately a people who lived at opposites to her own way of life in this rugged setting. Her subject has no equal within New Zealand. The island's climate, economics and population are of another world. Only the labels on the beer bottles indicate that this oceanic dot might be the eastern extremity of the Lyttleton electorate. The bulk of its people (no pun) appear to be of normal Maori descent in the dusty distance, but upon meeting, the visitor will be faced with a racial mystery. These people are descended from the salty mariners that were involved in the whaling and sealing trades of the nineteenth century who married into the resident Pomare subtribe. As a huge family unit, they are hospitable, humorous, placid and pugnacious by turn. New Zealand is never referred to unless the topic of deficiencies in Government is to rise in conversation. Local rumours run rife, colouring past social events into a complex pattern of inter-family intrigue. No harm is done and the tale is only half-believed after it has run its full course. When the appetite is up, a cattle beast will become an inverted skeleton where it was standing only fifteen minutes before, eels festoon clothes-lines and jet black feathers of the Western Australian swan follow the wind across the paddocks.

The major farms are operated by knowledgeable station managers for various syndicates. Despite their efforts, the returns are frequently marginal and are of constant concern. Politicians and departmental advisory bodies periodically flock through like ducks in the shooting season, thankfully returning to New Zealand to smooth out their ruffled feathers. Then a tough little body of locals retaliates by flying to the mainland to press their demands and be photographed by a curious press. The Government employees live on 'the shelf', a small delta of plateau elevated about fifty feet above sea level . This is the town of Waitangi.

Its only road junction is a mechanical circus for the island's serviceable road vehicles, about quarter of the 200 known to have come ashore. At night the whole area is audibly marked by the banging of its light producing diesels and the cheering from the Memorial Hall as yet another horse opera grinds away to the inevitable climax.

It was to this world that Elaine Grundy opened her amazed eyes after the 'Port Waikato’ had shattered the dream of her first ship-board cruise. Through a series of amusing kitchen explosions, she learnt the necessary extensions for successful Chatham cooking. By minor disaster their home was eventually redecorated. With physical discomfit she travelled cross country frequently with her husband to visit his scattered patients. It is from these adventures that her appealing story has come.

With the modern industrial intrusion of crayfishing and meat packing factorys, the Chatham Island way of life has been set for change and the 1950's can now be looked upon as being somewhat historical. This however, only goes to double the value of her literary contribution. Disappointingly, the illustrations are not her own but come from the National Publicity Studios. They do present a fairly good cross-section in a geographical sense, but as her story is mainly aimed at the resident islanders, I would have liked to have seen more locals grinning out at the reader, for surely this is their major characteristic - an ability to be amused under all circumstances. The map she has included is carefully marked with all the place names her text includes and would be a sound lesson to Mrs Richards ('The Chatham Islands’, Vol 2, No 1, page 19). All things considered, this book has good entertainment as well as educational value. Her observations, neatly manipulated and brought to good reader level, may well serve as guidelines today for someone fortunate enough to be going 'down to the Chats’ for a spell. I say 'fortunate' as Elaine Grundy winds up her final chapter with …. "I dumbly shook my head, finding no words to explain that my tears weren't for the parting with my husabnd - we would soon be reunited - but for the island, now a closed chapter in my life," In every case I saw of a departing expatriate, this emotional display escaped nobody.

Pierre.

******************

CAMPBELL ISLAND: Ian Kerr's continuing history has now reached the wartime Cape Expedition to the sub-Antarctic islands. It directly follows the June installment of the farming days on Campbell and the final chapter will appear in the next issue of 'The Islander' - Campbell as we have known it - a postwar scientific observation station.

Chapter 10: THE CAPE EXPEDITION

As far as is known, the only ship to visit Campbell Island between the time of the Warrens' departure in 1931 and the outbreak of the Second World War, was the R.R.S. 'Discovery II' late in January 1938, when she spent a few hours in Perseverance Harbour where soundings were taken. Both the Auckland Islands and Campbell Island were uninhabited in 1939 and both had harbours that could give shelter to raiders or their supply ships. An inspection of the islands by a naval vessel was therefore given high priority on the outbreak of war. Even before the declaration of war, HMNZS 'Achilles' had been ordered to join the West Indies Squadron and HMNZS 'Leander' had left Auckland with a garrison for the important cable station at Fanning Island. On 'Leander's' return she was fitted out for the voyage to the Subantarctic, and left Auckland on 25th September.

The cruiser steamed into Perseverance Harbour on the morning of 28th September. Venus Bay, Garden Cove and Tucker Cove were carefully examined. A landing was made without difficulty on the remains of the pier built by the Shetland Islanders 35 years before. The sheds were in a bad state of repair but a serviceable skiff, a punt and a boat slip were in fair condition. No signs of recent human occupation were seen and 'Leander’ made for the Auckland Islands. Port Ross was entered and nothing suspicious was seen but bad weather prevented the ship entering Carnley Harbour. She returned to make a more thorough search of the Auckland Islands in November but nothing was found.

The crew of the 6,100 ton German steamer 'Erlangen' had cause to be thankful for the bad weather that kept the 'Leander' outside Carnley Harbour for their ship was hiding in one of its inner arms. She had sailed from Dunedin on 28th August for Port Kembla in New South Wales but had been ordered by radio from Germany not to go there. She had insufficient coal to steam to South America, so she made for the Auckland Islands where the men cut 400 tons of rata wood and fashioned sails from hatch covers. The 'Erlangen' left in October before the 'Leander's' second visit and reached Southern Chile on 11th November. She crept round into the Atlantic, but was intercepted by HMS 'Newcastle' in July 1941, was set on fire by her own crew and finally sank.

The first German raider to enter the Pacific was the 'Orion' in May 1940. She laid mines in the Hauraki Gulf in June, one of which claimed RMS 'Niagara’. The 'Orion' hurried away to the north but returned to the Tasman Sea in August, when, on the twentieth she met and sank the 'Turakina’. She moved away to the south and on the twenty-fourth, Awarua, an Australian station and three stations in the East Indies reported radio direction-finding bearings on a German Naval Unit, which formed a triangle in the centre of which was Campbell Island. HMNZS 'Achilles' was immediately ordered to the area but before she could reach the island the order was countermanded. The Admiralty had concluded that the bearings were "reciprocals" and that the signals had come from a vessel operation north of Scotland. The 'Orion' had, in fact, sailed south of Australia towards the Indian Ocean but returned to the Pacific in the following month and joined forces with the raider 'Komet’ and the supply ship 'Kulmerland' in the Caroline Islands. The group decided to move southward across the eastbound shipping lanes from New Zealand and on 25th November, near Chatham Islands, sank the 'Holmwood'. Two days later and 450 miles to the northward they sank the 'Rangitane’.

Just before these encounters the Auckland and Campbell Islands had been searched again, this time by HMNZS 'Achilles’. No evidence was found that enemy ships had sheltered there but the possibility that they might do so remained as strong as ever. Obviously the chance of an occasional visit by a British warship and a call by a German ship coinciding was slight and evidence that a raider or supply ship had been in one of the harbours would be of little value. In any case, the time for these inspections could ill be spared by the overworked vessels at the disposal of the Naval Staff. On 19th December 1940, therefore, the Chief of the Naval Staff requested the Secretary of the Organisation for National Security to place on the agenda for the next meeting of the Chiefs of Staff the question of whether steps should be taken to place observation parties and W/T stations on the Auckland and Campbell Islands.

The Public Works Department and Air Department had already been consulted as Commodore Parry's memorandum gave some details of costs and the number of men needed and said that the auxiliary schooner 'Tagua’ operated by the Works Department would be available from 15th February to the end of March. The success of the operation, the Commodore said, depended on its being kept 'most secret’ and he suggested that it should be known as the "Chatham Islands Expedition."

The detailed proposal was finally approved on 29th January, 1941, and planning went ahead rapidly under the Senior Signals Officer, Navy Office (Lieutenant-Commander C. Nicholson, R.N.), assisted by Wing Commander E. Gibson, RNZAF, and the acting Aerodrome Engineer, Works Department (Mr D.O. Haskell), Dr R.G. Simmers (Meteorological Service) and Dr R.A. Falla (Canterbury Museum) who had been members of Sir Douglas Mawson's 'Discovery' expedition to the Antarctic seas in 1929 and 1930, provided advice on sub-polar living conditions. The code name for the expedition was changed to "Cape Expedition." Three coast-watching stations were to be established: No l at Port Ross and No 2 at Carnley Harbour in the Auckland Islands; No 3 was to be at Perseverance Harbour, Campbell Island.

During February 1941, the preparations were given new urgency when the Navy Office received two pieces of information. The first was a report of the sighting, by a Sunderland flying boat on 16th February, of the 'Orion' and the supply ship 'Ole Jacob' steaming southward near the Solomon Islands. They had, in fact, been ordered to the Indian Ocean and intended to pass through the Tasman Sea. When they saw the Sunderland they separated and the 'Orion’ swung far to the east and then southward past Chatham Islands and well to the south of Stewart Island on 5th March, the day the 'Tagua’ left Wellington with the advance party for the islands. (The 'Komet’ had left the Pacific a few weeks before; in doing so she went right down into the Ross Sea, much to the surprise of German Headquarters.) The second piece of intelligence was that the pocket battleship, 'Admiral Scheer’ might attempt to reach Japan to score a propaganda triumph by defying the Royal Navy.

The document that set out the objectives of the coast watching parties was given point by reference to these sightings and surmises. It was estimated that the earliest the ' Admiral Scheer' could reach the Auckland or Campbell Islands was 12th March. In fact, she returned to the South Atlantic and reached Kiel on lst April.

The parties' object was to report any ships visiting the Auckland or Campbell Islands and to continue reporting without being detected. Their first task on arrival, therefore, was to select observation sites that commanded good views of the harbours but were not themselves easily to be seen.

At Campbell Island, as soon as the Perseverance Harbour camp and lookout were established, a track to a point overlooking North East Harbour was to be made so that it would be kept under observation every other day. If Monument and South East Harbours could be used by shipping, a track was to be prepared to a position on Mount Honey from which they could be inspected at Weekly intervals. The duties of the first parties also included the establishment of permanent camps that could be occupied for the duration of the war "in such comfort as the climate and siting of the camp will allow;" the investigation of alternative local sources of food supply, and the investigation of the possibility of growing vegetables. It was planned that , when these instructions had been carried out, any spare time available after coast watching duties and the necessary household chores was to be devoted to exploration of the interior of the islands and such geological, zoological, entomological and botantical investigations as the parties were competent to attempt. And, of course, the taking of weather observations was not forgotten. All previous scientific visitors had been able to spend no more than a few days on the islands, here was an opportunity for more exhaustive observation, particularly on the life, or seasonal, cycles of the plants and animals.

The 'Tagua’ left Wellington with the advance party on 5th March 1941. The party was under the command of Assistant Aerodrome Engineer, E.C. Schnackenberg who was to supervise the establishment of the camps. Accompanying him was E. Suckling, responsible for the radio installation, the three leaders, L.J. Stannaway, G. Jones and A.M. Fletcher, and another radio operator, B. Evetts. Master of the vessel was James Broadhouse (later Lieutenant RNZNVR). They reached Carnley Harbour eight days later and, after selecting the site for No 2 camp, set about getting the gear ashore. Early in April, while exploring the Northern Arm evidence of the 'Erlangen's' call was found, and on 7th April, M.V. 'Ranui' arrived.

It had been intended to provide a launch to enable Camps l and 2 to keep in touch but later it was decided that the parties should have a means of escape if a German raider did make use of one of the harbours as a base, and the purchase of a suitable vessel was authorised. The M.V. ‘Ranui', 57 tons, was selected and taken over at Bluff by Captain W.R. Webling, formerly chief officer of the Government steamer 'Matai’, taken to Wellington for overhaul and repairs, and sailed for the Auckland Islands towards the end of March. She was to be used for periodical coast patrols and servicing to the stations. When not engaged on these duties, she was to lie up in one of the east coast inlets of Auckland Island where the crew was to establish a fourth lookout station.

Shortly after the 'Ranui' arrived with more members of the shore parties, the two vessels sailed for Port Ross where No l site was selected. The 'Tagua' then returned to Wellington and left there again with the remaining stores, equipment and men on 29th April. Dr R.A . Falla was on board this trip as observer and organiser of the biological activities of the parties . Very bad weather was experienced and the 'Tagua' spent six days in the vicinity of the Auckland Islands unsuccessfully trying to make a landfall. Finally she had to return to Dunedin for repairs. On the next attempt she was unable to beat past Nuggets, but after a second return to Port Chalmers, the 'Tagua' finally reached the Auckland Islands on 4th June. Ten days later she sailed for Campbell Island and entered North East Harbour on 15th June where the men inspected the valley at the head of the harbour and climbed to over 1000 feet on the ridges above it. They found the remains of the Cook Brothers' whaling station; a small tin hut was still habitable; a bunkhouse had been dismantled and much corrugated iron in good condition, and heart kauri flooring from it stacked; there were six cast iron blubber pots in perfect condition. The next day they collected four boat loads of timber, iron, bricks and piping, and sailed for Perseverance Harbour. The first attempt to enter the harbour was unsuccessful but the destination was reached on 17th June. The site selected for the camp was a short distance up the valley from Tucker Cove under Beeman Hill, and the lookout on a shoulder of that hill commanded a view of the entrance to the harbour. The remains of the woolshed and residence were investigated and much of value was found: tools, kitchen utensils, books, paint, oil, etc. Unloading the ship and building the camp went ahead at smart pace and the latter was ready for occupation on 25th June. On the same day radio communication was established with New Zealand. The 'Tagua's' departure was delayed by unfavourable weather reports from the mainland until 6th July. She dropped the emergency radio hut and stores at North East Harbour and arrived back at Wellington on 11th July.

The men left behind to await relief in nine months time were L.J. Stannaway (leader), N.Trustrum (radio operator), E.W. Mitchell and R.F. Wilson. With up to 20 hours of daylight in summer, not too much time was left over from coast watching for other duties. At first, it was considered necessary to avoid making conspicuous tracks to the lookout points and the journey from camp would take up to half an hour. Once there, a watch had to maintained for about six hours. Conscientiously carried out this was not the relaxing occupation it might seem to be. Furthermore, in the first year, the posts were makeshift, uncomfortable shelters, affording little protection from the weather. Cooking, cleaning and general maintenance were other necessary duties and, in the early days, improvement of the camp, outbuildings, tracks and drainage occupied much of the rest of the time. The living quarters were comfortable. They consisted of pre-fabricated plywood houses with double walls. Basically there was a living room, two bedrooms, kitchen and larder but the sections were interchangeable and with ingenuity such additions as closed-in porches and bathrooms were possible. Radio communication with New Zealand was restricted to one two minute schedule every 24 hours and, normally, private messages could not be passed either way. For general news, the men had to depend on the news broadcasts. One weather report was transmitted to New Zealand each week.

In spite of the heavy demands made on the men by necessary duties, time was found to begin survey work in the near neighbourhood of the camp and for preliminary work for biological and geological surveys.

The relief of the first parties was effected in March 1942, again by the 'Tagua.' The parties for the second year increased to five men each. The leaders were again surveyors and one member of each party was qualified as a scientific observer. In this year, the Campbell Island leader, L. Clifton, completed a survey of the island and J.H. Sorensen began the valuable biological work he was to continue the following year and, as leader, in the fifth year. Sorensen also undertook auroral observations.

The routine of the second year was as before but conditions were improved by the erection of huts at the lookouts and additions to the camp buildings. Tracks were made more permanent with corduroy. The meterological programme was increased and in June 1942, a new schedule tor transmitting three observations a day to New Zealand began. As well as raiders, the coast-watchers had now to watch for possible invading forces from Japan but the year again passed without incident.

The parties for the third year were again taken to the islands by the 'Tagua' in January 1943. While at Campbell Island, the 'Tagua' was recalled urgently to Auckland lsland and her passage thither was an example of the difficulties these small ships encountered in the stormy latitudes south of New Zealand. She took four uncomfortable days to traverse the 135 miles between the Islands. The changeover at Campbell Island was completed in early February.

As a measure of protection in case of invasion, the men this year were all attested as Army personnel, with equal rank as privates. They were issued with Temporary Staff badges and special duty passes, and were well fitted out with army clothing and equipment. A trained meteorological observer was included in each party and also a man with experience as medical orderly. Men qualified to carry on the biological programme were again sent down. The strange fascination of these wild, lonely places that had drawn shepherds back year after year was again in evidence. Four members of the 1941 parties and one of the 1942 parties volunteered for a second tour of duty. The year 1943 saw the installation of ionosphere sounding equipment at Campbell Island; it was, at the time, the most southerly in the world. Results of the soundings were transmitted to New Zealand in code in April, but the apparatus then failed. It was replaced by new equipment in January.

In May, the ‘Ranui' returned to Dunedin so that her captain, L. Lindsay, who had injured a knee, could receive medical attention. She returned early in July and brought a welcome supply of fresh vegetables and mid-year mail. To give the Campbell Island party the benefit of these, the 'Ranui' made her first trip to the No 3 camp. In addition to the other things, a supply of poison was taken to combat the rats which were a serious problem. She stayed at Campbell Island for a fortnight and was used by J.D. Knowles to make a running photographic survey of the coast.

The programme and activities remained as before except that the number of weather transmissions was stepped up to four a day. However, late in the year coast-watching was reduced to a few hours a day and the members of the parties other than the meteorologists and radio operators were able to explore the islands more thoroughly than had been possible before. In July and August of this year, were sighted the only two ships , apart from the relief ships, seen by the expedition; they were both allied merchantmen.

At the end of 1943, the 'New Golden Hind', commanded by Captain W. R. Webling, succeeded the 'Tagua' as relief ship. In addition to the new parties for the Auckland Island stations, she carried a survey party under Flying Officer A. W. Eden. This party paid a short visit to Campbell Island in January and February, 1944, to check on the survey carried cut by L. Clifton and then spent the rest of the year and some months of 1945 surveying the Auckland Islands. In November, 1944, a Catalina flying boat was stationed at Bluff in the hope of making aerial surveys of the islands but, after two or three abortive attempts over Auckland Island, the project was abandoned.

The new Campbell Island party went down in the 'New Golden Hind' in January 1944 and on the same trip, Lieutenant C. Whitmore, RNZNVR, and Dr R. A. Falla inspected all the coast-watching posts. On this trip and the previous ones, the official documentary film, '50 Degrees South' was made by the Chief Officer, R. P. Whitchurch in his spare time. The reduced programme of coast watching was continued for some months but in May the Naval Board decided there was no further need for it. The Board considered, however, that the islands should not be unoccupied and, consequently, decided that the No 1 party on Auckland Island and the Campbell Island party should remain until the end of the year, but that the No 2 Auckland Island party should be withdrawn. The camp was abandoned on 3rd June 1944.

In October 1944, the Director of the Meteorological Services pleaded for the continued occupation of Campbell Island, at least, to provide weather reports. He discussed the value of the reports to New Zealand and World meteorologists; the importance of the ionosphere observations near the auroral belt; and even the possibility of farming the sheep to help offset the expense. As a result of these representations the usual arrangements for the annual relief of the two parties went ahead and the Auckland Island team went down in January and the Campbell Island men in February 1945. The 'Ranui' was used for both operations.

A further meeting, convened by the Director of Scientific Developments, was held in Wellington on 6th February 1945 to discuss the future of the stations. Much the same ground was covered. The Ministry of Works representative considered that, as a safeguard in the event of an emergency, the 'Ranui' should remain at the islands. In fact, the Ministry would not accept responsibility for the job unless this was agreed to. In addition to the possibility of reestablishing the sheep run, that of reviving the sealing industry was also mentioned.

It was decided to abandon the Auckland Islands but the party there was not withdrawn and the camp finally closed until Flying Officer Eden's survey party finished its work. The Cape Expedition came to an end, as far as the Auckland Islands were concerned on 3rd June, 1945.

In the meantime, at Campbell Island, Sorensen back for his third year, now as leader, hoped to devote much time to biological survey work. He found, however, that much maintenance and repair work was now needed about the camp buildings. A boatshed was built and the water wheel used to turn electrical generators was reconstructed. A wind charger was also brought back into use. Much of the timber and iron for this work came from the buildings of the old sheep station.

On 17th June 1945, a RNZAF Hudson, taking advantage of exceptionally good weather flew over Campbell Island and dropped urgent mail. In October 1945, the members of the expedition, private soldiers it will be remembered, were demobolised, and this act can be taken, conveniently, as marking the end of the Cape Expedition.

What did it achieve? From a military point of view an answer is not possible. The enemy may have become aware that the islands were occupied and kept clear of them, or they may never have thought to use them. German raiders had sheltered at Kerguelen Island in the Indian Ocean. We do not know but, whatever the case, the decision to place coast-watchers on the Auckland and Campbell Islands was undoubtedly a prudent one. For geologists, botanists, ornithologists and other naturalists it was an opportunity that would not otherwise have been presented to them. The results of their observations on the islands and of their studies of material collected have been published by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in some fifteen monographs. But perhaps the greatest benefit that came to New Zealand as a whole from the exercise was the establishment of a permanent Meteorological and Ionosphere station on Campbell Island many years before it might, otherwise have been possible.

(To be Concluded)

********************************

ALRIGHT YOU SUNDAY COOKS

Line up on my left and look smart about it. Now this 'ere cooking appliance is for the preparation of all meals which is to be ‘ot on this 'ere island. You will approach it smartly from the front and by numbers load the breach with this lot of rotten coal right on top of last night's embers. If, on observing yellow sulphurous smoke discharging from the ports, you will step back two paces and shout in a clear voice, "Help." You will then close all windows and leave smartly at the double by that door over there.

“Now pay attention ‘ere. No cans of baked beans may be placed directly on the ‘ot coals unless the lid has been ventilated in at least six places. The chimney is not allowed to become red ‘ot as it scorches the tea towels. And leave the place tidy for cook on Monday morning you bloody lot or you are on a charge."

"On the top shelf over there you will see the manual for preparation of food proper for 500 airmen at one and fruppence a time. All you do is divide the quantities wot is given by firteen five 'undredths - if you lousy lot ever went to school. If you can't, get a friend to do it. I don't want to starve 'alf way through July. "Smarten up now. ‘tenshun. Right turn. Quick march - left, right, left, right ……. "

Photo by Rex Firman.

*************************

Book Review: MURIHIKU

by Robert McNab.

W. Smith, Printer. Invercargill, l907

Actually, the copy I borrowed was a facsimile edition by Wilson and Horton, a paper back with failing glue that had reduced its 377 pages to fifty separate serialised episodes. I had noticed recently that bale full of this edition had taken a prominent display in W & T's and wondered how McNab had struck such a belated success. Murihiku, as the Maori word suggests, deals with the history of the southern extremity of New Zealand - from Cook's arrival in 1770 to the fall off of the sealing trade in the late 1820s. To teach this, the book supplies almost equal space to Macquarie Island and the ships and companies that operated out of Port Jackson. Not surprising - the period's history makers would hardly be New Zealanders.

Nor is it surprising that the reader spends half his time at sea in a complex but highly accurate detail of shipping movements, from Macquarie eastwards to the Chathams. The profession was as hazardous as a thousand bomber raid and a sealer who could get himself through a ‘tour of ops' could regard it as fortuitous. Death by scurvy was as common as drowning. Death through cannibalism had its equal numbers with forgotten sealers dying of starvation. Never the less, the marine scene is extremely well presented and beyond the skills of a modern historian who will never sound the right note to a southern gale in a schooner's rigging.

For one who wants descriptions of the shore stations at Campbell and Auckland Islands, there will be disappointment. Of course there is adequate mention of Frederick Hasselbourgh's discovery of Campbell and his subsequent death there. But the Aucklands hardly receive mention despite the early sealing successes, and it is too early for the Enderby saga.

Three sections of McNab's work are unexpected and highly informative. The first deals with Cook's 1773 survey and Vancouver's later use of Dusky Sound. McNab knew the area well and draws the life and early times of New Zealand's remotest corner with ease and authority. The second section tells of the 1813 flax industry at Bluff and the reader feels as if he is peering deeply into a panoramic Heaphy water colour long before the infant Invercargill started its urban sprawl. And the informative handling of the resident Maori tribes in this area is a further relief from a prolonged tale of salt, sweat and seals.

For the average student who was compelled to jump from Cook to Marsden when at school, this microscopic section of our early history should not be missed. Perhaps the publishers of this new paperback saw it that way too.

Pierre.

****************************

THE ISLANDS REPORT IN:

CAMPBELL ISLAND

With only 4 weeks to go until the 'Holmburn' arrives, all the packing and cleaning for servicing are the main activities at the moment. The weeks since our Mid-Winter's swim seem to have flown past, and it is hard to realise that it is nearly all over. Everyone went in for the above swim, late on the Friday afternoon, but there was not much lingering around once it was over and we all had a warming shower and then the usual dinner and party which went on into the wee small hours.

As with the 'Acheron’, the Russians came to our assistance again when our mechanic suffered a stroke and the decision was made to evacuate him. The R.V. 'Shantar' arrived at 5.45pm on Friday night, 2nd August and with a very smooth operation, had embarked him and departed by 7pm. The doctor who came ashore was a very attractive female, but not a smile or expression could we get from her. However the crew of the pickup boat were just the opposite and much sign language took place on the wharf, one comment that we understood was that our Navy Rum taken straight was too weak, but by the look of some when they left it was a bit more powerful than they gave it credit for. As an aid for any future occasions I have ordered a Russian and Japanese phrase book to come down as at times I had considerable difficulty in making the Russian interpreter understand. A beautiful plaque was made by Tiny and Roger and presented to the crew.

A major disappointment has been the complete demise of our movie projector early in June made more so as we have a number of films which we have not seen and Friday and Saturday nights have not been the same without them.

A King penguin has taken up residence with us down at the wharf area. He has had a bad cut on his left hand side, which is slowly healing over, and we are force feeding him at present with some tinned fish. He is in much better shape now than when he arrived 10 days ago, but he nearly became a perfect statistic when he wouldn't get out of the way of the tractor. He is also given a daily hose down with sea water and seems to look forward to this each day.

I would like to wish the incoming party well for the 1974/5 season, and as this party includes a carpenter, plumber and electrician, a busy year would seem to be in store. I leave Campbell Island with few regrets and the year here will certainly be remembered for a long time. My thanks to all those back in New Zealand who have helped make the job down here easier.

Rex Firman.

RAOUL ISLAND

With only another 7 or 8 weeks to servicing it will be understandable that there is quite a bit of activity going on at present, with people rushing around the Island having a last look at things before they go. The works programme is just about complete except for the necessary tasks which by their very nature have to be left until the last week.

Our one big highlight since the last issue of the 'Islander’, was of course, the wreck of the yacht 'Moeroa' in Denham Bay. They had put in here on their way to Fiji because of rough weather and to carry out some minor repairs, unfortunately they couldn't get away again due to bad weather. None of the crew were on the yacht at the time of the wreck and very little was saved. Two of the crew of five were of the female variety which made for some rather unusual laundry hanging on the line and one of them ate like a horse though she insisted she was on a diet. A Mayday call to H/0 brought the 'Lorena’ in on her way back to Wellington to pick up the crew but what was quite funny was that as the 'Lorena’ pulled away from Fishing Rock another yacht pulled in. This time it was the 'White Scroll' which will be remembered by past Raoul parties. They stopped the day, had a look around the station and left to Tauranga the same afternoon.

Most of the beer has run out and at present Swampy Crompton, has got a fearsome looking brew gurgling and rumbling away on top of the fridge. For those completely out of beer there is much smacking of lips and belchings of pleasure over this evil looking and smelling brew which to me is suspiciously similar to a nameless substance encountered while working at Wellington Hospital. Still there's no accounting for taste.

The annual plaques are finished I'm glad to say. What a lot of head scratching there was over that. I would say without a doubt that the two most difficult jobs encountered all year were getting everybody together for the group photograph at Christmas and getting them to pose for their photographs is like trying to draw their eye-teeth. Never met such a bashful lot.

We have heard that the wildlife boys are coming up again this year but not until about three weeks before servicing. Still it's something for us to look forward to. To end this last contribution from the 1973/4 party we send our best wishes to all members of the Association and our special thanks to Auntie Staples who has to take all this burbling down. We lock forward to meeting you all at the next Reunion.

Mr M. Mouse (alias G.H. Charlton, O.I.C.)

(Thanks lads. A speedy servicing and a happy trip home -Editor.)