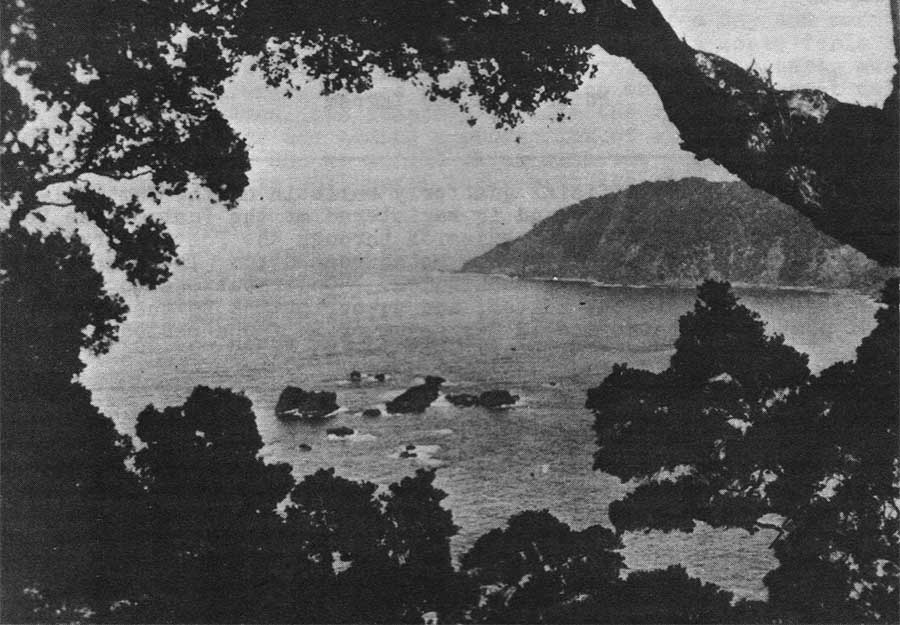

“Milne Islets, Boat Cove”

A view well known to Raoul Islanders at Raoul's end before

descending to the Boat Cove landing. D'Arcy Point is in the background

(Photo: the Alf Bacon Collection)

CAMPBELL-RAOUL ISLANDS' ASSOCIATION (INC.)

NEWSLETTER Vol 2 Number 2 MARCH 1972

Association Officers 1971 - 72

Patron

Air Vice-Marshall A. H. Marsh C.B.E.

President

Peter Ingram

| Secretary | Treasurer | |

| Ian Bailey | John Caskey | |

| Committee | Honorary Members | |

| Ralph Hayes | M. Butterton | |

| Len Chambers | H. Carter | |

| Robin Foubister | H. Hill | |

| Tom Taylor | I. Kerr | |

| C. Taylor | ||

Newletter Editor

Peter (Pierre) Ingram

"The Islander" is the official quarterly bulletin of the Campbell-Raoul Islands' Association (Inc.) and is registered at the Post Office Head quarters, WELLINGTON, for transmission through the Postal Services as a magazine. All enquiries should be addressed to: The Secretary, CRIA (Inc.), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON. Contributions to the bulletin should be forwarded to the Editor, and subscriptions to the Treasurer. Current membership rates are $2 per annum or $5 for a period of 3 years.

A Kind of Coming of Age:

I have always regarded a periodical or the like, which informs the reader within its introductory page that it has been registered at the G.P.O. for transmission as a magazine, to have an air of maturity and the stamp of permanency about it. So desiring these qualities for our own bulletin, I left a written plea within the hallowed halls of the Chief Postmaster one morning and after a gentlemen's delay of one month, received a pleasant note in the affirmative that we had made the grade.

A Distant Vision:

Alas, the majority of returning expedition members must be propelled back into the asphalt and concrete jungles of our cities to take up their chosen responsibilities after a short period where it has been possible to learn very thoroughly, what outdoor freedom is all about. Some require the pressures and challenges that can only be found in the totally man-made areas - others learn with a little regret that they were permitted a vision of something which they may have no permanent part.

Perhaps I am of the latter. I have always leaned towards the pastoral rather than the painted, due to my youth being spent in the King Country where the bush came to our back doorstep and the unpaved hills were the highways for our recreational pleasures.

The vision of Raoul Island came again with its usual force during an early morning jaunt in Wellington's Khandallah Park, to quench the extraordinary powers of endurance in my children. The fleeting lumps of cumulus against the summer sky and the variety of greens that stretched to the ridge in the light of the early sun could easily pass for those more northerly. Above all, the wind in this motley forest was in tune with the song of the Kermadecs. The youthful crashings of my older son's progress over the bush's brittle rubbish was perhaps a little loud for the hunted billy's flight, but the smell and the shapes of shade could have been the familiar signposts to Trig 5.

And there it was again, framed between my upturned toes on a Paekakariki beach. Wellington's Kapiti, shimmering blue, with its highest point a mock Moumoukai, the ridges tempered by age to be a little more shallow as our memory is by time so that we could do no better if we were to put pencil to paper. Raoul in reverse if we were viewing it from Meyer, but all in order if it were the first sighting from the South. How can one view Raoul from the South? Only at the commencement of tour. Ah, me.

Passing the Time of Month:

The phrase in its usual context refers to the passage of a day and normally infers a leisurely approach. To your bulletin editor, a month feels as though it were compressed into a day when he is working at the text, awaiting contributions or hovering at the printer's door while the normal delays occur. His promised deadlines leapfrog through the week and he feels like extracting the master and adding a postscript of apology. Eventually the thing becomes unstuck and he surges ahead with the posting formalities and swears that such delays will never occur with the next issue.

For the sake of uniformity, it is hoped that "The Islander" will appear in your mailbox in the first week of the months: March, June, September and December. If it does not - you will know the editor has slipped again. And he might just make such a slip in March, for he will be away on annual leave and will only return to Wellington earlier than Friday 3rd should the sunny and windless North not live up to its name.

The Editor

****************

THIS QUARTER’S CONTRIBUTIONS:

An article out of the ordinary but in full step with·the atmosphere we try to maintain in our bulletin, is Captain John F. Holm's account of the 1954 voyage of the M.V. 'Holmlea' to Auckland and Macquarie Islands. Timely too, in that this issue records Captain Holm's intended retirement under 'Members Comment’. Other major contributor is Alf Bacon with part one of his 'Journal of Events’ relating to the settlers on Raoul of 1889. Although Alf passed on during October of 1970 in his 100th year, he is still very much part of our association and is our link to the past in the history of the Kermadecs. It is a pity he did not live to see his articles published in the bulletin.

'Yesteryear' is a trial column in which we require old hands to look back over the past and recall items that have been covered by time. These snippets are invaluable for the record as they reveal the character and atmosphere of the earlier expeditions.

Certainly not neglected are the historical articles included by Ian Kerr and myself from time to time. Ian's last inclusion was chapter 5 · 'Scientific Expeditions from England and France' (Campbell Island 1840/75) in 11/12 and my last was chapter 3, 'By Way of a Living' (Raoul Island 1836/76) in 9/5. As you note, I have got a little behind and would have brought myself up to date in this issue, but for the rush to have everything to the printer before I go on leave. Alf's article can set the scene for my reappearance in the June issue.

The same rush has further postponed Brian Bell's and R.H. Taylor's article on the 'Wild Sheep of Campbell Island', which is to be illustrated by Dr Soper of Queenstown and he is still out in the Wilds of Westland at this moment.

And don't forget to review your year away chaps. Even a paragraph becomes of interest to all within these pages and just might make it a little easier for the researcher in years to come.

***************

MEMBERS COMMENT:

Conducted by the Editor.

It is some time now since I accidentally initiated the two salvos between Bill Sykes (D.S.I.R.) 11/3 and Don Merton (Wildlife) 12/2 on the coming and expansion of the rat population on Raoul Island 9/6. Certainly a most informative and valuable exchange of theory and fact took place which looks well within our pages and a source of excellent reference on the matter for all time. In a gentlemanly departure from the subject, Bill wrote last December "....I think I will leave the rat question to Don Merton although we will probably have to agree to differ over certain points." And comes usefully to the fore once more to answer my final paragraph on 12/5, re the vegetation on Macauley Island. "In fact," says Bill, "I almost suspected that you threw in the last paragraph as bait. Anyway, for what it is worth, the enclosed might be of interest."

The brief account of the visit to Macauley in 1836 by Captain Rhodes of the barque "Australian" is certainly of interest to someone studying Kermadec plants. Firstly, although there is no suggestion of a fire by Rhodes, I doubt if the island was burnt long before this date. In 1827, the French corvette ''L'Astrolabe" passed by Macauley and the naturalist Dumont D'Urville reported that the island was partially scrub covered. He made no mention of introduced animals so there were probably none there until after the island was burnt. Thus this event may have been between 1827 and 1836, but what is certain is the fact of a burn, because the evidence is obvious to this day in places. I took a sample of the burn line for radiocarbon dating and I was informed that the date must be very recent, i.e.well within the last century.

As for Rhodes reference to a few stunted trees on Macauley, I think that it can be safely assumed that these were mostly Kermadec ngaios. However, since he mentions the most elevated part he may have seen small trees of the Kermadec Homalanthus polyandrous in the little extinct crater just below the summit of Mt Haszard, because they were still there in 1887. Today there is no trace of them and the goats have reduced their number on Raoul to a mere handful - a pity, since this handsome tree does not grow anywhere else in the world.

The reference to “a little wild parsley" really made me put on my thinking cap when I read Rhodes journal. The possibility of it being true parsley is extremely remote, because although the whalers thought of their stranded comrades by introducing pigs and goats, I doubt if anyone would disagree with me when I say that they would not have gone to the lengths of introducing parsley to garnish a shipwrecked seaman's repast. There is one member of the parsley family native in the Southern Kermadecs but (a) it looks like celery more than parsley and (b) it has never been reported from Macauley and (c) the top of the Plateau there is not the right place for it to grow anyway. So what would parsley be likely to mean to a person from a fairly affluent background in early 19th century England (Yorkshire to be precise) ? After perusal of old horticultural books, I concluded that the ordinary little cut and curly leaved vegetable that we grow today as parsley had been developed from its wild progenitors well before this time and so would have been quite familiar to young Rhodes in his father's well tended vegetable garden. Therefore, some quite unrelated plant must have reminded him of it on Macauley and the only candidate to fit the bill, as far as I can see, is a little weed called Cotula australis (sorry I know of no common name). This has superficially similar leaves to parsley and particularly in the winter is very common on the Macauley Plateau. In 1966 it filled or ringed the entrances to most of the unoccupied petrel burrows. This is one of those plants about which it is difficult to say whether or not it is native or introduced but if I am right about it being Rhodes' "wild parsley" its presence on Macauley at this early date suggests that it probably arrived there unaided by man.

______________________

Snooping around the offices of the Holm Shipping Company for snippets of information the other day, I quite suddenly found myself handling an informal interview with the Chairman and Managing Director himself, after a courteous introduction by his able and attractive secretary. The alert features of Captain John Ferdinand Holm are known to almost every Wellingtonian through the periodic inclusion of his photograph in our daily newspapers when the Harbour Board elections are due.

Socially caught off balance by a recent frisking in Customhouse Quay a strong Southerly and dressed in clothes frequently paled by the saw dust and wood chips of my workshop, it took no time to feel comfortably at ease in the natural warmth of his manner and conversation. The only outward sign of a fine business sense was contained in concise and informative sentences over the ten minutes that I dared to detain him.

I felt a little sad to learn of his intended retirement in two months time, for with him must go the name of Holm to which we have directly related "servicing time" over so many years. His youthful enthusiasm towards a full and active trip abroad later this year, only strengthens my best wishes to Captain Holm and his wife for many happy years of well earned retirement.

Coincidentally, the “New Zealand Herald" carried a column on Captain Holm the following day (Friday January 21st)and as it contains the basis of our conversation and is a fine precis of his business years, I have included it for the record:

CAPTAIN HOLM IS TO LEAVE HIS LINE

One of the best known shipping men in New Zealand, Captain J.F.Holm, is to quit the family business when he retires as managing director of the Holm Shipping Line in March. The Holm Line is to be more fully integrated with the Union Steam Ship Company.

Captain Holm said yesterday that after more than 42 years in the shipping industry he felt it was time he was relieved of the everyday pressures of his job. He is 59. The Holm Line was begun by his grandfather in 1880 and run by his father from 1912 until 1952 when Captain Holm took over as managing director. Captain Holm said he had given the matter of his retirement a great deal of thought and felt that if there was a need for someone to take his place, it should be a younger man.

"Now is the right time and opportunity for me to make the break. Naturally I do so with very mixed feelings as shipping has been my life, and I hope I have contributed something toward its well being." He said he was pleased to see that some of his ideas concerning coastal roll-on-roll-off services and shipping services to the Pacific Islands were likely to be taken up by the company's new director. Captain Holm is one of the few former seafarers to head a shipping company andhis life at sea is widely acknowledged.

He began his sea career as a deck boy in the topsail schooner 'Huia' and later served with the Shaw Savill Line and Union Steam Ship Company. Later he worked for H.C. Sleigh Ltd in the timber ship 'Abel Tasman'. It was not until he was master of the 'Port Whangarei', that he actually worked for the family business. The ‘Port Whangarei’ was not owned by Holm Line but she was chartered by the company while he was master. During the war years, Captain Holm served in destroyers and corvettes with the Royal Navy. He was awarded the DSO for his work as commanding officer of a corvette in severely damaging a German submarine off the West African coast. His ship and the submarine were engaged in a night long duel which resulted in the loss of 12 German lives and severe damage to the U boat. Captain Holm's ship was also damaged and limped into Freetown with its forecastle awash after ramming the submarine twice.

After the war he continued to work for the family business and did occasional voyages as master of company ships. In 1968 he was appointed master of the New Zealand Company of Master Mariners, an organisation which was established in New Zealand before the Second World War to watch over the welfare of senior officers, seafarers and shipping generally. Captain Holm is also president the New Zealand Ship-owners' Federation and a member of the Wellington Harbour Board. His company first became connected with the Union Steam Ship Company in 1930 when the Union Line took an interest in it. The Union Company did not obtain a complete interest in the Holm Line until 1969 when the Holm Line was offered the control to two other coastal companies, Richardsons Ltd and the Canterbury Steam Ship Company in return for the additional shareholding.

Now the companies are to be more fully integrated with the Union Company as a result of the recent Union Company takeover. Captain Holm said he always believed in rationalisation, particularly in the transport business, and while there was a very strong sentimental attachment for him with his company, he could not deny the benefits closer co-ordination would achieve. "In fact, I believe that this is necessary for the very survival of the industry", he said.

Captain I.A.McKay will take over as head of the Holm Line Shipping interests on Captain Holm's retirement. Captain McKay is at present the company's general manager."

_________________

So the "General Grant" sleeps on under its watery blanket around Auckland Island's west coast. Noel Shirtliff has temporarily abandoned his attempt to retrieve the gold bullion that went below on the night of the 13th May 1866 (11/5). The "Evening Post" for Tuesday 19th January carried this comment as well as a little history on the fishing vessel "Picton".

"OLD SHIP WENT FISHING FOR CRABS - THE TREASURE MUST WAIT”

The fishing boat Picton is just one of the little ships that come in and out of the Wellington Harbour - but she is a ship with a difference. Probably she would be the oldest of her kind, having been built as far back as 1917. During her youth she traded round the New Zealand coast as a lighter. Her master is Mr Alan Aberdeen, well known in fishing circles and formerly master of the ‘Tuhoe’ in the Wellington-Kaiapoi trade before the ship was laid up.

Only recently the "Picton" was in the news when it was reported that she was to be hired by a Wellington syndicate to look for the wreck of the "General Grant" with its lost gold treasure at the Auckland Islands. But this venture is now postponed indefinitely. The "Picton" was built by Brown and Sons at Te Kopuru, near Dargaville, as the "Koau" for Richardson and Company of Napier, being registered at that port. A cutter-rigged vessel, she is 87.7 feet long, 22 feet in width, and has a draught of 9.5 feet. Her name was changed to the "Picton" in 1952. Gross tonnage is 144 and net 77. Captain Aberdeen said the "Picton" was still a good seaworthy little ship getting good catches of fish. But they were not receiving the price for the landed product that they should. Fishing is by line only and the vessel works off the Mernoo Bank, east of Banks Peninsula, and around the Chatham Islands.

On the last trip, Captain Aberdeen spent three weeks around the Auckland Islands with a party of geologists catching specimens of the southern spider crab, which measure up to 8 1/2 inches across the body, with 12 inch legs. The venture was an exploratory one to investigate the possibilities of commercial fishing for the crab, but there were not as many as was hoped for.

And the "General Grant's" gold which at todays values would be worth $2,000,000, will lie on the floor of the ocean for at least a little while longer. It has been there now for 105 years. The organiser of the expedition was a Wellington man, Mr N. Shirtliff, who hoped to sail south to the Auckland Islands, 280 miles from Bluff, this summer with his six man party. He said his plans had been set back because of a lack of equipment and a potential shortage of capital. The cost of the expedition had risen to about $30,000. The "General Grant", wrecked on the night of May 13-14th, 1866, with great loss of life, was carrying gold bullion worth pounds 150,000 ($300,000). In addition, a number of miners were carrying their hard won hoards with them when the ship went down. The vessel is supposed to have foundered on the western side of the main island, and a series of expeditions have failed to turn up any gold.

"The wreckage of the vessel, and hopefully the gold, must still be there. It is just a question of finding it", said Mr Shirtliff. "We have studied the proposition very thoroughly and have narrowed the search area down. There are roughly 28 miles of coastline there, and our prime search area will cover two miles. The water depth does not exceed 80 feet and there should be no problems in that respect."

Mr Shirtliff, a foreman on a large earth moving contract just north of Wellington, was formerly of Nelson."

____________________

A very welcome letter from Eddie de Ste Croix (C61, 64, R68) out at Chathams where he reports the first branch meeting of the CRIA occurred on the 8th January at his Waitangi house - it being "a most convivial and memory evoking evening” Those present were Larry Jarnet (Met R69), Robb Stanley (Ion C51, 55), Dennis 'Speed' Horan (Radio Op C48) and Fred Buitenkamp (Mech R64, 69). Alan Averis (Farmer R61) had only just left Chathams for New Zealand three weeks previously but Bill Stuart (Mech C69) has turned up at Kaiangaroa, and the lads hope to have him over at the next meeting. 'Speed', by the way, claims a record of sorts - 14 minutes to the top of Mount Beeman from the Tucker Camp. Eddie goes on to say:

"There is one point we would like to take up with 'Pierre', the reviewer of books. This fellow 'Pierre' is quoted as saying that "summer days are rare" on Chatham Island (12/19)."

"Untrue, Untrue", remonstrates our Eddie. "We, the Chatham Island sub branch of CRIA take collective umbrage at this meteorological type mistake, which we are sure was an honest one. Sun-bronzed, shorts wearing, and cold beer drinking ex-heros of 997 and 944 would like to see this matter attended to in the next newsletter." Will agree with you Eddie, that your present summer is a beauty and temperatures will remain mild so long as you stay to the windward side of the harbour pack ice. Best wishes for a happy tour.

*********

A JOURNAL 0F EVENTS, PART ONE

by Alfred Bacon

The following is the first of three slightly abridged articles from a journal written in the 1940s by the late Alfred Bacon, each installment dealing with one of the three periods that Alf was resident on Raoul Island. His writing forms no part of my historical articles, which have still to reach this period, but I do add a small introductory paragraph to set the scene.

After the Kermadecs had been taken possession of by the New Zealand Government in 1887, it was decided that 5620 acres of Raoul would be opened for selection upon the Small Grazing Run tenure. Four runs subsequently became available to the public, of which two were underlet to cope with the needs of the 1889 settlers, approximately 24 in number. The settlers' would-be trading vessel, the 90 ton schooner 'Dunedin', was lost at sea while returning to New Zealand after taking the first party to Raoul. Alf's party followed on the Union Steam Ship Company's ‘Wainui’ in September of 1889. We take up his story after their arrival at Denham Bay. (Ed.)

The 1889 - 91 Settlers on Raoul Island

"The boats were kept afloat just outside the breakers by means of a line from the stern of the boat to a kedge anchor, another line from the bows to the shore was held by two men, who hauled the boat in or let it out as the waves came and broke on the beach. Each time the boat was hauled in, those ashore had to rush down the beach as the wave receded and grab a package before the next wave broke, and I can tell you there was no time to be lost. Sometimes a man and his package would be washed up the beach spitting out salt water and sand, another time he would get drawn into the under-tow and would go out of sight for a while, package and all, but unless the package was very heavy it would be washed up later.

We were lucky though; all our stuff was landed fairly dry, as a lot of goods were packed in barrels. After all the excitement was over, the beach looked as if there had been a shipwreck, boxes, barrels and packages of all kinds strewn along the beach. The ‘Wainui’ steamed away, and left us stranded with no transport. However, that did not bother me, I was in my glory in the wildest and most romantic place I had ever been in, where there was plenty of natural sport in the shape of goat hunting, cliff climbing - and the cliffs were mostly from 500 to 1500 feet high, with deep ravines cut into them, and all thickly wooded with Pohutukawa, Nikau palms, tree ferns and a dense undergrowth. The fishing was great, nearly all the fish are very large and heavy lines have to be used. Quite a few turtle come to feed round the island, but never come ashore. I have often shot them, and sometimes they wash up, but mostly sink and are never seen again. Coming back to the morning we landed, which turned into a lovely day; the first thing we had to do was to erect our two tents both being 12 x 14 feet and have all the stuff stowed away. Bunks to be erected, water to be got from a lake that was in the bay, and that was the colour of cold tea, wood for the campfire, and a number of other things to make ourselves comfortable for the night, but were we ? The heat was too much and the rats were there in hundreds keeping us awake nearly all night. I forgot to mention I had a dog, a bull terrier, and didn't he play havoc with those rats - they were laying in all directions next morning.

My father and I spent three days making our camp secure and comfortable, then we went to look at our town acre, which every settler was supposed to have on the flat in the Bay, our main section being up on top of the cliff about 1000 feet high - and so hard and steep to get at, that none of the settlers even bothered to look at the area. The town acre was covered with dense mass of fallen timber where a hurricane had been, and a growth of six foot high ‘ Cherrypie’ prevented anything from getting through. So we decided to leave it, and shift our camp up to the lake about a half mile from where we were camped. It took about a week to carry our stuff up to the lake and fix the camp again. In the meantime we interviewed some of the settlers and found out that their opinion was the same as ours - the outlook was hopeless as regards trying to ship stuff from the island - having lost our transport and the landing impossible at times. So most of the settlers decided to leave at their first opportunity. A few weeks later a German Man-of-War came in sight of the island. Signals were sent in the shape of smoke and a white sheet waved and she stopped. We all thought she was coming in - but to the disgust of all who wanted her to do so, she steamed away to Auckland. We all settled down to wait results then and do a bit of exploring, fishing, etc. There were oranges, lemons, grapes, shaddocks and a patch of bananas about half a mile long by two chains wide. These had been planted by Baker and Reid who lived there with Samoan wives and children sixty years ago. The bananas had grown so thick that they crowded one another out and made the bunches very small, and the shaddocks were very sour. Peaches were also growing. We found turtle meat to be just like beef but much more tender. On the beach was a large try-pot the whalers had evidently left some years back, for trying down the whale blubber, but it had got gradually covered with sand and it has never been seen since. One young man of the party had a rather narrow escape from asphyxiation one day. He and his brother were digging a well for water and after going down about ten feet, a rush of poisonous gas almost rendered him insensible. His brother reached down and got a grip of his hand and after a struggle managed to haul him out. Sometime after I happened to be passing the well and noticing blowflys hovering around it; they were evidently attracted by the bad smell of the gas, and when they went about half-way down, they fell to the bottom like stones falling - overcome by the gas. I got a long pole to put down the well and found there were quite eighteen inches of flys all over the bottom - a good trap.

Myself being of an adventurous spirit, was foolish enough to climb a very rocky steep face of a cliff over a thousand feet high one evening after some wild goats. Of course as I climbed - so did they, until the darkness began to come on and not being able to go down the way I came up, I went farther until it got so dark I could hardly see my way. In the cliff a narrow and deep ravine came in my way and I almost walked into it. I could just see a tree that had fallen across it, so crawled on my hands and knees along its length, and then jumped thinking I was over. However, something prompted me to put my arm around the tree - and it is just as well I did, for my legs were dangling in space. I climbed back as well as I could, having my rifle in the other hand. My next bad turn came when I was straddle-legged on another tree that was growing out from a perpendicular rock face about a drop of 500 feet. I suffered with the cold all night, only having a thin shirt on and the sea breeze blowing on me. To add to my discomfort it began to rain just before dawn and it can really rain there when it likes. Then I shivered until there was enough daylight to see where I was going, and climbed to the top of the cliff, hanging onto roots of trees and pulling myself up rocky faces by branches of trees or vines - or anything I could get hold of. I reached the top and then there was a job before me to find the track I had heard of called the Mutton Bird Track, but as luck would have it I found it without any trouble, and although it was a break-neck track, I reached camp none the worse for my night out.

The beach in Denham Bay is about two miles long, and I have seen it almost covered with eggs of a tern called the Wide Awake. The eggs are the size of a pullet's egg and are quite good to eat, not fishy but something like a duck egg. When cakes are made with them they become pink because of the yoke colouring. A Mr Bell and ten of a family were living on the North side of the island, having been there some ten years after arriving by the schooner ‘Norvel‘ from Samoa. They had a very trying time when they landed in Denham Bay, not knowing the climate was so humid, their flour was not protected and became mouldy. The rats ate all the seeds they put in and everything that finally grew - so after nearly starving, they moved to the other side of the island where the rats were not so numerous. Still they had a hard time until they got a few seeds to take. The mutton birds were very numerous and they are good eating, but rather hard to preserve so many went bad before a successful method was found. So their main food was goat meat and fish for quite a while, though fish was rather scarce during the winter. After a while, they became master of the situation, and when we got there they had an abundance of food, in fact it was often wasting. Mr Bell sent his two sons over to us to give us an invitation to visit him which we did, and when we got there I was quite surprised to see what a beautiful place he had; it was a true Garden of Eden. I saw banana groves, pineapples, grapes, passionfruit, figs, peaches, guavas, pomegranates, custard apples, pawpaws and others too numerous to mention. While staying with Mr Bell he told us that if we liked to settle on a piece of land of his, we could have it to use as long as we lived on it. We accepted the offer and made arrangements to get all our things around by boat, the one that the Association had hauled up on the beach in Denham Bay, a large ship's boat. The settlers gave us a hand with our stuff and took it around the island; everything was shipped and landed through both surfs safely without getting wet. Some articles were packed on our backs over those cliffs and through the bush, but the shipped stores also had to be carried along the beach, over the rocks and up the two hundred foot North coast cliff to where we were going to settle. A whare was built, the frame of poles was thatched with the leaves of the Nikau palm, an iron chimney and plenty of firewood made us comfortable. The mutton birds were plentiful and some of them had to be put down for the winter - the young ones before they are ready to fly. So we went to work by building a smoke-house first, as they must be smoked after salting and pickling, then packed into barrels with a weight on top to force the oil out of them, which rises to the top and keeps the air from the carcass. Every morning my father and I got one hundred birds, plucked, cleaned and salted them down - put the former hundred into the smoke-house and got half rotten wood to smoke them with - then got up all through the night to see to the fire. That was done until we had eight hundred birds put away, and we were glad when they were. The oil of the birds is very good for cooking and can be used many times.

After that job we cleared land to grow vegetables, but the caterpillars were bad, and ate nearly all the things we put in, except pumpkins, and they really grew at a rate. We had plenty of stores, with fish, goat, meat, turtle and mutton birds we fared well. In a climate like that with plenty of exercise and pure air, no one could be anything but strong and healthy. After being on our section for a few months, we were surprised to hear the horn of the Government Steamer 'Hlnemoa' and everyone was rushing and tearing about with excitement - and when the captain came ashore, we learned that he had been sent to take those away that had signaled the German Man-of-War. It appears that when she got to Auckland, one of the sailors was in some bar having a drink with his mates, and mentioned the signals they saw on the island. A reporter of one of the papers happened to hear the conversation and it was put into the paper. Some of the friends of those on the island saw the report and thinking some serious trouble had come to their friends on the island asked the Government to send the ’Hinemoa’ over to enquire into the matter, which they did, and that is how she came six months early on her annual rounds to service the depot at Curtis Island. However, the steamer took those away who wished to go, about ten of them. Captain Fairchild was in charge of the ‘Hinemoa’ then, and a good old sort too. He told my father to get all his belongings ready to be shipped aboard the ’Hinemoa’ in about six months time if he wanted to get away, which he did. My father considered the island had no prospects for me, my age being eighteen at the time. So we carried our belongings back to a low flat near the beach where they would be taken through the surf to be shipped. A rough shack on the flat was to be our home until the steamer came again."

(to be continued)

******************

TO RETIRE THIS MONTH: (photo: Holm Shipping Co.)

Captain John Ferdinand Holm, Chairman and Managing Director

of the Holm Shipping Company is introduced (Members' Comment)

and writes the feature article in this bulletin.

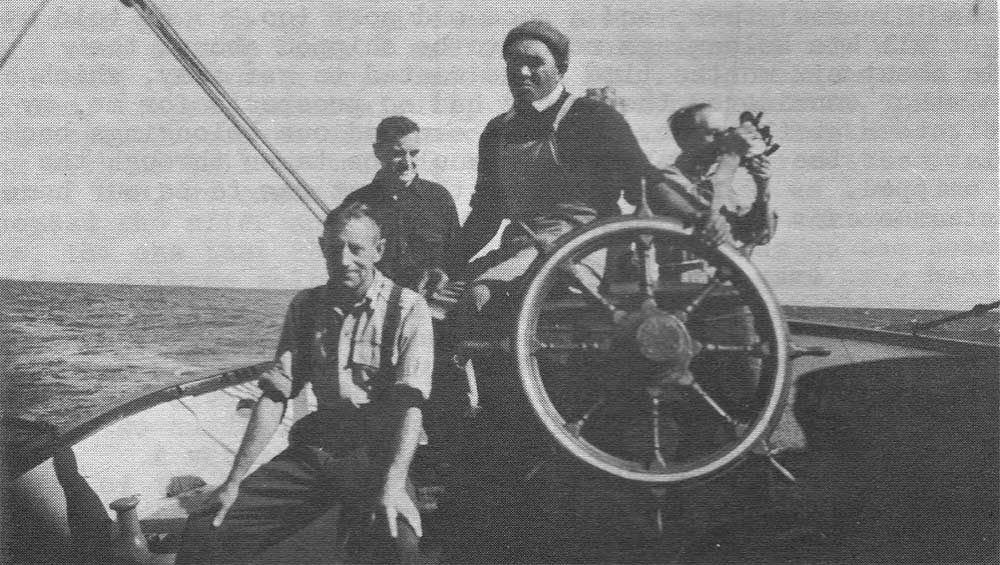

NEW GOLDEN HIND SAILS NORTH ( photo: C. Taylor)

The head Rarotongan seaman holds the schooner on a northerly

course from Auckland during May of 1948. Captain Coleis seen,taking

the noon-shot to the right of the group.

Southren Skua on Lyall Ridge, 1970

(photo: Dr Michael F. Soper)

_________________

The OCHWOTACULTS

It is almost a decade now since Martin Davidson (technician, C64)made the astounding discovery of the Albatross Cult, a primitive tribe who were resident on Campbell Island for many centuries. Its people were of enormous stature, finding no difficulty in standing in the tussock while using the basalt buttress of Filhol as a sacrificial altar for the periodic slaughter of the virgin female albatross. The dates involved for the ceremony came from a complex mathematical calculation, necessary because the phases of the moon were too difficult to determine due to low cloud frequently obscuring the nocturnal orb. Speech amongst the people consisted of a series of whisperings and honks, not unlike the sounds of the wind in the tussock and the local wildlife, the only noises with which they were familiar. The race was eventually wiped out by its people coming into contact with a social disease introduced by American whalers of the last century, despite a prescribed diet of mouldy bread which was supposed to alleviate the plague.

The full history is very well recorded in the Filhol Carvings, which unfortunately was beyond the range of the most powerful binoculars kept on the DER “Hissem". The Davidson Lectures ceased soon after a suggestion from crew members to forego the normal home brew and hospitality of Beeman Camp and take their Polaroids into the area. There was also the fear that too wide a publicity from the National Geographical Society could induce an influx of American Tourists which was not in keeping with the wishes of the Internal Affairs Department, by whose good grace we were allowed to be stationed in Campbell Island.

******************

YESTERYEAR NOT SEEN:

these days is the colourful queue of Campbell Islanders to be outside the clothing store at Shelley Bay for the free handout of battledress and kitbag.

NOR PRAISES SUNG:

for the Patron Saint of Campbell Island, the placid St Mungo who had a built-in shrine on every one of the thousands of packets used on Campbell, the contents of which must have been responsible for the 'soapy' weather of 53 South over the years.

******************

"HOLMLEA" UNDER A.N.A.R.E.

VOYAGE REPORT TO MACQUARIE AND AUCKLAND ISLANDS

MARCH, 1954.

"Under the orders of A.N.A.R.E." was reminiscent of wartime practice to those on board M.V. “Holmlea” when this N.Z. coaster recently forsook humdrum coastal trading to do a "mercy" trip to Macquarie Island under charter to the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition.

“HOLMLEA” sailed from Wellington shortly after 7 pm on the evening of the 12th March, direct for Auckland Islands. The weather experienced on the run to the Island was good all the way, mostly with a light favourable wind. There was however, a long and moderate easterly swell, throughout the latter part of the journey.

The Auckland Islands were sighted on the late afternoon of Monday, the 15th March, and pleased indeed we were to see them. As it is very near the equinox, darkness set in about the same time as it would in New Zealand, possibly a few minutes later, and the next few hours were rather anxious ones, as the whole success of the timing of our trip depended on departing from Auckland Islands this same evening. If we had been delayed until the following morning, it would probably mean a night time arrival at Macquarie Island and consequent delay there also.

I had hoped to be a few hours earlier in arriving at Auckland Islands, and it was getting very dark as we closed the land. How much faith I wondered, could I place on the charts of Auckland Islands ? I did not feel that they could be given great reliance. However, after a good deal of misgiving we managed to make out the entrance to Port Ross a few miles in the distance before it was completely dark, (and if any stranger should be entering the port in the future, it is worth noting that the bay just to the north of the entrance could easily be confused with it in the half light).

Hoping hard that the chart was reasonably accurate, we stood in, not daring to slow down on account of the rapidly fading light. The scientists got their considerable quantity of gear ready (which included food for 3 weeks in case of emergency) between anxious glances at the shore, and I think they were duly impressed at being landed on the tiny beach in the darkness on this small uninhabited island 750 miles from their port of departure.

After we dropped anchor at about 2000, one of our scientists, a Naval Voluntary Reserve Wartime officer, expressed his relief and a few words of encouragement and hope for our departure. This however, was not worrying me much the worst was over now, as the way out was fairly straight forward, and would be assisted then by a beautiful full moon shining right through the entrance.

We anchored about half a mile off the small and only landing place on Enderby Island where the Scientists were to be put ashore. The surf boat was lowered and scientists and gear were landed on the beach about 8.30 pm. The party was greeted by a large herd of Sea-lions, one of which made a snap at a member of the boat's crew, but was rapidly and effectively repelled by one of the scientists, Mr Dell who gave it a good hard hit on the nose (its most vulnerable spot)with a piece of drift-wood. The landing was rendered quite difficult by the unusual easterly swell running into the harbour, and after the scientist and gear had been put ashore the surf boat dragged her anchor home, and broached broadside on the beach.

It was only with considerable difficulty, and with assistance of the men landed that the boat’s head was finally pushed seaward and she was able to proceed back to the ship. We were just commencing to lower a lifeboat from the ship to help with the proceedings when those on shore were successful. No damage whatever was one to the boat and fortunately the men on shore had dry clothes in which to change, and contrary to reports in New Zealand the boat shed was found in comparatively good condition. They were, therefore, able to sleep in this shed throughout their stay on the island.

The most amusing incident about this episode was the short, but excellent swimming dash by the Chief Engineer, who was instructed by the Second Mate in charge of the surf boat to swim out to it, after they had got the boat clear as he would not risk going back on the beach. The Second Mate did not realise that the Chief Engineer was clothed in thigh sea-boots, which are reported to make swimming impossible. The Chief's protests were not heard in the boat through the noise of the surf, and he had no option but to swim for it. He was pulled aboard in a somewhat exhausted condition. The boat was reloaded and we weighed anchor at approximately 10 pm and proceeded down the east coast before taking departure for Macquarie Island.

The weather on the way to Macquarie Island was again unusual in that we experienced mainly easterly weather, with a continuation of the easterly swell. Visibility was not good, and unfortunately decreased on the day we picked up Macquarie Island. With poor visibility on the afternoon of Wednesday 17th, it was my intention at about 1.30 pm as land had not been sighted, to alter course to the southward, till the ship reached a dead reckoning latitude half way up the 20 mile length of Macquarie Island, and then to steam slowly into the Westward if visibility permitted, until land was sighted, as this coast of the Island is clear of outlying dangers. However, just as we were turning to follow this procedure, we sighted the Judge and Clark Islands, which lie about 8 miles to the north of the northern end of Macquarie Island. We headed straight for these Islands, and taking departure from them, picked up the headland to the south of Hasselborough Bay, known as Handspike Point. By this time, visibility was very poor, and it was most difficult to establish a correct position, although I felt confident we were somewhere in the entrance to the Bay. We were in radio telephone communication with the Island, but they could not see us from shore, nor could they hear the ship's whistle. They lit a big fire on the beach, which although not visible at the time, later proved very helpful.

Owing to existing conditions I deemed it advisable to drop the anchor and lower the surf boat which was to endeavour to establish our position, and guide us the correct anchorage. Before the surf boat was in the water, the weather temporarily cleared, and we were able to define the beach, and the Anchor Rock, and weighed anchor and proceeded about ½ mile nearer to the beach.

The usual Bay worked when landing stores at Macquarie Island is Buckles Bay, which is on the opposite side of the narrow Peninsula of Hasselborough Bay, but owing to the easterly swell, we were unfortunately unable to work Buckles Bay, and for this reason we landed the stores and embarked the sick man from the beach in Hasselborough Bay.

Conditions were far from pleasant during this time, the ship was rolling in the heavy swell, although conditions on the beach for the surfboat was reasonably good. The wind was from the South East, fresh and very cold, it was raining moderately and visibility was never more than one mile, often only a few hundred yards or less.

The First Mate, and Chief Engineer proceeded with the boat's crew ashore in the surf boat, and after landing mails and cargo, proceeded to the living quarters on the Island, where they had a pleasant sojourn with the men at the station while they repaired a portion of our windlass, which had been broken when heaving in the anchor at Auckland Islands, and also filled a tooth of the Chief Engineer's which had been paining him greatly on the trip down from New Zealand. This was done by a Danish Doctor on shore, and was apparently a very good job.

Owing to the circumstances and the prevailing weather conditions I felt it inadvisable to leave the bridge during our 5 1/2 hours in Hasselborough Bay, and in consequence I was feeling very cold and miserable and it was for this reason (and because I felt I should let those sitting comfortable in their office chairs in Wellington know) that in my radio message to Head Office I added the two words "weather unpleasant". These two words were apparently the cause of press statements in N.Z, that we were encountering bad weather. During this time while watching bearings, the anchor cables, and when visibility permitted, the proceedings on the beach, I had ample time to think of the old days of the sailing ships, and some of the astounding stories I have read of the castaways and of the brutalities of the early mariners in these regions, which in the early 19th century, were a regular refuge from justice; and of the inhuman and mass slaughter of seals and penguins which occurred on this island for the glory of wealth, and in complete disregard of other consequences.

In spite of very persistent persuasion on the part of the men on shore to remain for the night, the boat was back at the ship by 8 pm. The hoisting on board of the boat was extremely difficult, owing to the rolling of the ship, but was finally completed without accident, and we weighed anchor and departed from the Island at 8.45 pm.

The men at the station at Macquarie Island were extremely pleased to see some new faces and their welcome was most enthusiastic. They made every effort to persuade us to stay with them for the night, but did not understand the circumstances which made this, of course, impossible. However, we gathered by conversation with them the next day, that they had celebrated our visit most enthusiastically, even though we were not included in the celebrations. As a parting gift to us, they sent four penguins out in the surf boat, but we did the only possible thing with these and promptly threw them over the side.

Bleak and desolate though the island is, I had been interested in Macquarie Island because the great Australian Sir Douglas Mawson had been a great friend of my mother and he considered it of major importance to Australia as being an ideal sanctuary for the bird and sea life of the sub-Antarctic.

The island itself looks most inhospitable and there is no vegetation worthy of the name, certainly no trees, shrubs or grass. Though we were astonished to learn that they boasted of one domestic cow "Betsy" which by dint of great care had so far weathered the summer months, whether it would come through the winter without being turned into beef was a matter of grave doubt. On what it lived we never really found out, but we did take the opportunity of replenishing our supply of fresh milk.

As an interesting side line on the value of food in the sub-Antarctic, it might be said that Macquarie Islanders offered us 1 cwt in tins of Asparagus, 1 cwt in tins of Salmon and a quantity of tea, in exchange for even a small portion of yeast. Unfortunately for us, conditions were such that I would not agree to the boat making a second trip, or we would have been very happy to have done the swap. The yeast was apparently not for the making of bread; it has been suggested that homebrew was behind it.

The voyage back to the Auckland Islands as mostly against moderate head winds, and the easterly swell still persisted. The Islands were sighted shortly after daylight, on the morning of Friday 19th March. We closed from the southwest, and one of the most outstanding landmarks proved, as we drew closer, to be Disappointment Island off the west coast. This is the island on which the barque “Dundonald” was wrecked in 1907 and where the castaways from this ship were compelled to undergo some of the most remarkable privations and heroism, ever known to mankind before they reached the main Auckland Island where they found the provision depot and finally the remaining dozen of the crew of 28 were picked up by the N.Z. Government steamer "Hinemoa".

It was in this vicinity also, that the "General Grant" was wrecked in a cave in 1866 and took to the bottom a fortune in gold which is still the subject of prospective salvage. I doubt however, if anyone will ever recover the treasure from this inhospitable coast where it is easy to imagine a ship sailing into one of the caves which abound. All along the south coast are sheer cliffs with indentations and numerous waterfalls quite picturesque when viewed from the sea.

A little before 11 am we entered the Harbour or Strait at the south of the Islands, which separates Adams Island from the mainland, and is known as Adam's Strait, or Carnley Harbour. We proceeded up this Harbour for nearly one hour. It is a very fine harbour and somewhat resembles the Marlborough Sounds. We would have liked to have proceeded right into the inner arm where the German S.S. “Erlagen” anchored in the early days of the last World War, and replenished her bunkers with Rata scrub. H.M.N.Z.S. "Achilles" also anchored in this harbour a week or two after the German ship had departed, and while searching for her. Time, however, did not permit our going up this far, as I was anxious to embark our scientists, complete the other objectives of our voyage and sail again from the Islands before dark. We went up just far enough to see the Government Provision Depot, and Boat Shed, on the shore. From the look of them that we observed, they seemed in extremely good order, the roof was clearly painted red, and the sides of the shed white.

We proceeded out the harbour up the east coast of the Island, and entered Port Ross again at about 3 pm. The surf boat was lowered as we passed Enderby Island, and it proceeded to pick up the scientists from the same beach as we had landed them on four days before. They were found in excellent health, and had had a successful and enjoyable stay. They found about 25 cattle still on the island, and their other research work was completed. Before leaving Wellington, they had been warned of the likely ferocity of the wild cattle and were therefore agreeably surprised when they found that instead of putting back their ears, smoking from their nostrils, and wildly charging them, the cattle did in fact turn around and gallop (if cattle gallop) in the opposite direction. Their rifles were not needed for the cattle.

Our scientific bretheren wished to proceed to the next small Island, known as Rose Island, to procure some samples of rabbits. We, therefore, dropped them there in the surf boat, which then proceeded to Erebus Cove, where the ship had just anchored. Erebus Cove is the place where the Enderby settlement was established in 1849, and ended in 1852, with much pathos, ill-feeling and bitter disappointment to the promoters. The climate and isolation had beaten them.

We proceeded ashore, mainly for the purpose of painting the tombstones on the little grave yard there. We had been asked to do this before leaving Wellington.

There is also a provision depot and boat at Erebus Cove, and these both seemed in reasonable condition. I was surprised to find when wading ashore with thigh seaboots full of water (owing to the thickness of the kelp preventing our getting close to the beach) that the water was not particularly cold.

Walking up from the beach, the first clearing in the bush contained the ruins of a wooden hut, and it was here that we thought we had found the grave yard, and I am still of the opinion that at least there was one grave there. On a piece of wood at the head of this grave, there was the following inscription "EDVIN SODERBERG". Two or three of the party proceeded a little further from the beach, and then discovered the real grave-yard. There were five or six graves and tombstones here, but the writing was not legible on all of them. The tombstones I read quite easily were engraved thus: "JABEZ PETERS, Late Mate, Barque DUNDONALD R.I.P." (In reading the story of the “DUNDONALD” disaster, it is apparent that although Mr Peters did in fact die on Disappointment Island, his remains must have been transferred later to the main Auckland Island.) The second tombstone which was easily readable had the following words: "Sacred to the Memory of John Mahony, Master Mariner, Second Mate of ship “INVERCAULD” wrecked on this Island 1864. Died of starvation." From what is written in the book "Castaways of Disappointment Island" it appears likely that John Mahony was the only man to get ashore from “INVERCAULD”. He was found dead in the forest with a few limpet shells around him and a small piece of slate on which he had scratched the name of his ship. There was another tombstone, which referred to an 8 month old child, which died during the period of the Enderby settlement. The name could not be read. On another rough piece of wood was the following inscription "Erected by Crew of S.S. "SOUTHLAND" over the remains of a man who had apparently died from starvation, and was buried by the crew of the "FLYING SCUD", Sept.1865.

As daylight was showing signs of fading we could wait no longer. No sign of the former settlement was seen, but had we followed the track which lead through the thick bush, we might have encountered some sign. However, as it is a hundred years since the settlement was abandoned, signs of it may quite easily have vanished. Before leaving the grave-yard we painted the tombstones with white paint, we had brought ashore for this purpose. We did not take off our hats while this was done. We should have, and I regret not telling the party to do so, but I am sure nevertheless, that all of us had a feeling of deep respect and were very thoughtful in the near presence of the remains of those who had died on this lonely island.

All around Erebus Cove there is thick vegetation, mostly Rata forest but with quite a few other specimens and some very nice looking ferns. There were numerous small birds (I have no idea of the species) which were very tame and obviously not accustomed to the intrusion of queer humans on their lonely domain.

Back on board "HOLMLEA" we dispatched the surf boat to collect the Scientists from Rose Island, whence they had collected some fine specimens of rabbits, the fur of which was particularly attractive, some a sort of silver grey in colour and I am told there are very few of this particular kind in New Zealand. We weighed anchor, met the surf boat opposite Rose Island, stowed it on board, and left the Harbour at about 10 pm. By this time, there was a full moon shining in the entrance to the Harbour, and it was indeed a very lovely night, as it had also been on our call at Port Ross during the voyage south.

If, therefore, I had been asked to make a report on the Auckland Islands, I should (although no doubt greatly prejudiced by the pleasant look of the land and the favourable conditions under which I had seen it) agree with the favourable reports which encouraged the Enderby brothers to establish their settlement there, just over a hundred years ago. No doubt also this impression was the reason for the exiled Maoris from the Chatham Islands who were found inhabiting the place when Enderby arrived, having sought refuge there a few years previously. I understand that several very good reports on the island were received. Experience, however, has proved that conditions are not favourable for settlement.

The voyage back from Auckland Islands to Dunedin was uneventful, we experienced mostly light head winds, and arrived at Dunedin at 11 am on Sunday, the 21st March.

Everybody on board thoroughly enjoyed the trip, and all comments were most favourable. The ship herself behaved like a lady and it would be difficult to find a better vessel for this type of work. She has sufficient power to enable the vessel to do a little more speed when required, and behaves excellently in any kind of weather. All ballast tanks were carried full throughout the voyage, although on the last two days, it might have been advantageous to have emptied the Forepeak tank. The vessel carried about 130 tons of steel loaded all over the floor of No.1 hold, and the forepart of No.2 hold. This trim would appear to be ideal.

The charts of the Auckland Islands are fairly inaccurate in places, but there are plenty of good landmarks; and provided the weather is clear, navigation around the Islands should present no difficulties. The harbours are splendid, and could not be bettered.

During the time we were at Auckland Islands, we wore the New Zealand Merchant Navy ensign, but we encountered no Argentine Man-O-War with which to pass pleasant courtesies.

Radio telephone communication throughout the voyage was good and transmission and reception of messages was carried out with little difficulty. Our communication with Macquarie Island itself was extremely good, and we were talking to them frequently for four or five days.

The three scientists from the Dominion Museum and D.S.I.R. were very pleasant and very conscientious men. We gathered that the trip had been very successful from their point of view. From our point of view, it was a pleasure to have had them with us. Their work included a study of the vegetation of the Island, and also the cattle, rabbits, seals, and bird life. They were particularly interested in ascertaining the effect on the animal life of inbreeding and living in isolation away from contact with other animals, climate and surroundings which could affect their health and condition.

The four passengers slept in the Officer's Saloon, during the voyage. They were given mattresses on the deck and used their own sleeping bags.

Unfortunately, we were unable to comply with the request from Geophysics Division of the D.S.I.R. to take soundings at intervals throughout the voyage owing to defect in the Echo Sounder. We did cast over the side the drift cards supplied by Oceanographic Division as requested. We also took samples of the sea water in the bottles provided by the Carter Observatory.

We sent frequent weather reports to the Meteorological Office in Wellington and also received from them, very helpful broadcasts specially prepared for "HOLMLEA".

The surf boat is an extremely good boat for this work, in fact had we not had it, we could not have done the work in the time. The crew although of the surfboat worked extremely well, on every occasion, each time they received a thorough wetting.

Captain J.F. Holm

******************

NEWS FROM THE ISLANDS

REPORT FROM RAOUL ISLAND

On December 8 USCG Northwind arrived under command of Commander Norman Venskie, USCG. Arrival brought farmer John Weir back on the station, after a six week visit to New Zealand. Mail received and after distribution most of the lads were off to their rooms to catch up on correspondence. Hospitality was extended to the Captain of Northwind and air crew. A proper morning tea and a quick look around the station. They were most impressed by our facilities. Commander Venskie presented on behalf of the ship a silhouette photograph of the Northwind in the pack ice some where in Antarctica. This was accompanied by a bottle of imported Beefeaters Gin. We reciprocated with a bucket of fresh cream and large quantities of fresh eggs, along with a bottle of naval rum.

The helicopter commander was an old hand, having visited Raoul on previous occasions. The weather was appalling and the ship had to steam around Denham Bay in order to operate her choppers. The stratus ceiling started falling down to about 5-600 ft with occasional squally showers.

One ton of gear was back-loaded for New Zealand.

A passing yacht came within half a mile mid December, did not respond to our communications. Have it from a reliable source this vessel was crewed entirely by women, numbers unknown …. still can't figure why they never called, after all, we had only been away from civilization for 5 weeks !

The garden bug has hit the Island, in particular marrows. The Raoul Island Marrow Growing Club was duly formed on January 8th and a committee was elected. A list of rules (in any order) was made including rules against sabotage and chemical warfare. It was hoped that the Skipper of the Staton Island would be able to judge the contest for us, but it appears the boat is arriving earlier than expected.

Fishing Rock has had a ramp removed by explosives and this makes operation of baskets and trays much easier. Large masses of concrete to be poured on this project when reinforcing, cement etc arrives.

Christmas came and went suddenly, the usual complaints followed excessive quantities of food and drink. The chef played his part in looking after everybody's palates very well.

A fishing competition is being persued with interest. At the moment Enoch Lavin leads the field with a 70 Ib shark. The front runner in the Kingfish Stakes is Moki with a 50 pounder, small we admit, but a start.

The goats are getting wary of trampers and shooters moving about in the bush. 96 animals to date have been removed.

Promotion. Last mail letter received from a German stamp collector. Sends envelopes addressed to the Governor General, Republic of Raoul, Kermadec Group, New Zealand. Only trouble is, the entire text of his letter is in German !

Have heard through the grapevine that Dr Stewart Wilson is taking up new appointment. We thank him for valuable services rendered and wish him all the best in his new location.

Congratulations also to Don Baker for his promotion, same Department, one floor higher. Many thanks for your assistance during the past years.

Moki McGREGOR

******************

REPORT FROM CAMPBELL ISLAND

That four months of our stay on Campbell Island has already been is hard to believe and the general feeling is that it seems no longer than four weeks, whatever the time though, we have had several interesting events.

The rugby season has been and gone and after some bloody encounters at Bulbanella Park, Shorty Wilkinson's Wellington team was able to narrowly claim victory over Bomber Brown's Hawkes Bay team by 28 points to 18 points, and Chris Glasson's Southland / Canterbury team by 63 - 15 points. There is still some haggling over the HB/Wellington encounter when it was realised after the match that the Wellington players had illegally worn shoes instead of the regulation gumboots !

An ambitious scheme by some members to climb the 15 peaks of Campbell Island in 24 hours was contemplated and the first three, Neville Brown, Mark Crompton and Keith Herrick set off. However, by the time Mt Dumas was attempted the weather had deteriorated to gale force winds with hail showers, and they failed, literally miserably after doing only 5 peaks. A further attempt is still likely.

A very welcome visit by the USCG Northwind with stores and mail was made during December and once again the Americans could not do enough for us and to them we extend our great thanks.

Christmas Day saw the U.S. Naval Research ship "Eltanin" in the harbour and their 40 scientists, including 2 young female technicians and crew came ashore. After viewing some of the Island's wildlife the festive season was celebrated in traditional Campbell Island manner in a very over crowded lounge. Came the time to rejoin the ship a number of individuals had to be steered down the Marsden matting and insisted on swimming from the wharf in spite of the very miserable weather. We Campbell Islanders were kindly invited on the “Eltanin” for a typical American Christmas dinner but this was a little upset by rapidly worsening weather with the ship dragging anchor.

A third surprise visit was made early in January by the seismic survey ship “Aquatic Explorer". This vessel operating for Shell-BP-Todd is continuing a seismic survey for oil on the Campbell plateau and for the last month have been operating within 30 miles of Campbell Island.

We Islanders were very interested in the sophisticated equipment and their satellite navigation system. While a contaminated fuel system was being cleared technicians and crew came ashore and were also treated to traditional Campbell Island hospitality.

Weekend excursions, especially to the hut at Bull Rock and Northwest Bay are frequent with finishing touches still being made to the Northwest Bay hut. Wildlife work is forging ahead under the capable direction of Mark Crompton, alias 'The Hen'.

Of particular interest at the Royal Albatross Study Colony is an albatross incubating two eggs. This apparently is a very rare occurrence for this species and we are watching it with interest.

Aqua sports in Perseverance Harbour have also been to the forefront on our occasional fine summer's day. Keith Herrick has built yet another boat out of the plywood from the radio sonde boxes and a small motor has been attached as a power plant. It is not fast enough for water skiing, but it is still a lot of fun. Chris Glasson a frequent underwater diver and myself have had a few interesting dives in the harbour. The 60ft high kelp forest with giant crabs climbing amongst it and occasional sea lions around us, plus 80ft visibility makes this a particularly interesting diving area. George Money has recently been introduced to the fascinating underwater world.

Station work is progressing well in spite of the unforeseen little hitches which invariably show themselves. The leaks in the hostel, technical building and ionosphere building have at last been whacked. New Marsden matting has been laid around the hostel and also, laying is almost complete between the technical building and the hostel. Water tank cleaning is in progress and after seeing what has been in the bottom of them it is little wonder that beer has been preferred to water over the years. On the recommendation of a fire inspector at the annual servicing, diesel dumps have been relocated behind the power house and this is fitting in with an ambitious scheme to reduce drum handling at the servicing.

Vince SUSSHILCH

******************

RECOMMENDED READING: FOURTEEN MEN

by William Arthur Scholes.

Published by Cheshire Pty Ltd, Melbourne, 1949.

The war was well over and the rehabilitation of manpower was in its final phase. The explorer / scientists on meager budgets looked once more at the maps of the southern ocean and the great white south beyond. The work programme was so indescribably vast in extent that the mere fringes must have appeared like glacial pebbles within their parent body. Inside the scattered array of its quaint prefabs, ANARE gathered its postwar material strength by issuing pleading memos to the storekeepers of the Armed Services. Everything the scientists acquired had the irremovable defense stamp on it - from battledress to barges. ANARE's chief exec and leader, Group Captain S.A. Campbell, one time pilot for Douglas Mawson's 1929 Antarctic Expedition, had little trouble in finding adequate men to fill the scratchy clothing and load the means of conveyance for the journey south.

Bill Scholes story of this period starts with a pub scene and quickly builds up to what Campbell requires – a three prong attack (the wartime jargon lingers on, it is 1947) which will take in Heard Island, Macquarie Island, and a coastal survey of Adelie Land. Both islands will receive semi permanent scientific stations which will serve at least five years before further review. The two ex-RAN ships will peck away at the southern ice and do what they are able. The degree of success cannot be forecasted. Scholes will go with thirteen others on the LST 3501 (later known as the “Labuan” , which served ANARE for 4 years until towed out of the Great Australian Bight after the '52 servicing to become a total writeoff 7/7.) to Heard Island, after which 3501 will refuel at Kerguelen, proceed to Melbourne, then Macquarie before going to the pack ice at 125 to 151 East. The diminutive 'Wyatt Earp', no bigger than a sea-going trawler, is programmed for Adelie Land, Heard Island to pickup Campbell by April '48 and back to Melbourne - God willing.

Scholes writing has its best pages in the trip to Heard and the month long servicing which followed. If 3501‘s builders could have foreseen what their product was in for, with true American financial diplomacy, they would have removed the welders and called in Rosie the Riveter, as well as phoning Bethelehem Steel to double the gauge before she even slipped from the drawing boards. Had someone else been writing the book, you would have known that Scholes was never going to make it and the rest of its 273 pages would deal with a blow by blow account of a vertical descent to Davy Jone’s Locker. What follows the bruised fingers of servicing, is a rugged (due to poor facilities) and routine account of day to day life obviously extracted from his own diary. In his sixteen months at the Corinthian Bay camp he rarely ventured beyond a two mile radial, but does draw useful reference from the field writings of the surveyors which is informative as well as being very much in keeping with the book's atmosphere. Scholes by postwar profession is a sport's journalist which possibly is the reason why he forces a system of rather irritating short sentences at the reader. Lost with this treatment is the climatical reappearance of the 3501’s master, Lt Comm. Dixon, one dark and stormy night when the ship is understood to be halfway to Australia. The diary format makes subject matter somewhat repetitive and does not attain the literary grace and skill of Temple's ‘The Sea and the Snow' (5/12) and Brown's 'Twelve Came Back' (7/7), both books dealing with Heard Island in later years. My first reading of 'Fourteen Men' contains perhaps the ideal prescription for full enjoyment. It was one of the six books that I found time to read while I was down on Campbell Island in 1964. I read a chapter or less a night before 'lights out', while buried deep in the warm bedroom comfort of the Beeman Camp. I loved the correct level of wind noise that the insulated walls would permit to enter my room and the sub-antarctic wildlife that restlessly grunted and snorted in the same valley were related by kind, if not by recent descent, to their counterparts on Heard.

Of surprise was the extent of the Corinthian Bay camp, some 20 huts in all, four being ex US Signal Corps octangle buildings that one sees in photographs of the Macquarie Island station. It is pleasing to me to note that the 'met' section got the building assigned to them for erection, up in only three days. It was the camp's lavatory. The book's photographs are good in quality, but as a Campbell Islander, I would have liked more station life shots, rather than the stereotype views of local wildlife with which we are so familiar and can easily find in our own albums. Missing are the excellent aerial photographs taken during the one and only flight of the RAN Supermarine 'Walrus' which was unfortunately storm wrecked only a few days after her arrival at Heard. Style or format aside, there is little doubt that Scholes thoroughly enjoyed his tour of this remote island. The experience was sufficient to move him to England in the following year, where he gave a series of lectures under an educational trust. Taken in small doses members are in for a good fort- night's reading.

Pierre.

______________

Heard's sparse history is thought to have commenced in 1833 when the British sealer and explorer Peter Kemp in the 'Magnet' was suspected of having called there. But the island's name is derived from Captain Heard, who in the American ship 'Oriental' passed by in 1853 but did not attempt a landing. Recorded honours of First Ashore have therefore been bestowed on another American, Captain Henry Rogers of the ‘Zoe’ and 25 crew members, some of whom 'wintered over’. That was 1856. The research ship HMS 'Challenger' was accorded a frosty welcome by resident sealers during 1874, so pressed on with a rough coastal survey which they completed in one day. With sealing at an end after this date, nothing disturbed the mountain's isolation (for this is what it is - an oceanic snow covered pyramid of some 9000 feet in altitude) until the arrival of a German expedition in 1902. Promptly selecting the highest peak and dubbing it 'Kaiser Wilhelm' (now know as 'Big Ben') they were up anchor and once again pressing southward for Antarctica.

British interest in the island did not begin seriously until 1910, when a South African whale factory ship, 'Mangaro’ landed a party. In the same year the British ship 'Wakefield' sailed past and reported violent volcanic explosions from the main peak. In 1926, a South African company was granted exclusive rights to the sealing and mineral wealth of Heard and the nearby McDonald Islands for the annual payment of $200. The lease was terminated in 1934. Sir Douglas Mawson was the last visitor of note in 1929 before the ANARE activities.