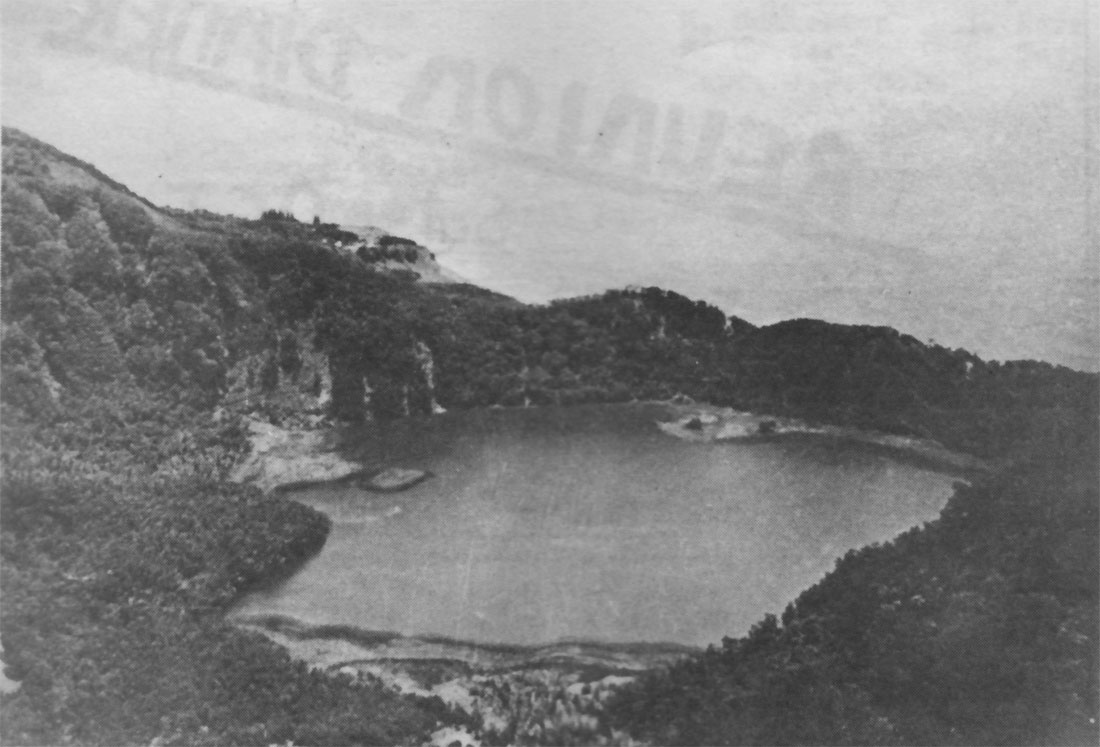

The view from Raoul's Moumoukai, takes in Blue Lake and the shallower

The view from Raoul's Moumoukai, takes in Blue Lake and the shallower

northern crater rim. Fleetwood Bluff shows as the treeless coastal headland

in the centre background. (photo: A Gardiner 1944)

CAMPBELL-RAOUL ISLANDS' ASSOCIATION (INC.)

NEWSLETTER Vol 2 Number 4 SEPTEMBER 1972

Association Officers 1971 - 72

Patron

Air Vice-Marshall A. H. Marsh C.B.E.

President

Peter Ingram

| Secretary | Treasurer | |

| Ian Bailey | John Caskey | |

| Committee | Honorary Members | |

| Ralph Hayes | M. Butterton | |

| Len Chambers | H. Carter | |

| Robin Foubister | Capt. J. F. Holm | |

| Tom Taylor | I. Kerr | |

| John Walden | C. Taylor | |

Newletter Editor

Peter (Pierre) Ingram

"The Islander" is the official quarterly bulletin of the Campbell-Raoul Islands' Association (Inc.) and is registered at the Post Office Head quarters, WELLINGTON, for transmission through the Postal Services as a magazine. All enquiries should be addressed to: The Secretary, CRIA (Inc.), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON. Contributions to the bulletin should be forwarded to the Editor, CRIA (inc), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON.

THE CASE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT

Cocktail and cigar fumes polluted Stockholm’s long summer twilight for the first half of June in what must have been the world's largest yet man-made conference, 350 United Rations delegates backed by 1500 representatives from most countries around the world, fenced politically and warily with 1000 news hungry reporters while an estimated 10000 students stood in the wings. The city's normally adequate accommodation quickly developed annexe out to 50 miles from the city centre - and the cause - The Case for the Environment.

Nobody knows much at this stage, Principles have been adopted but the general need for security which must bind any massive gathering so that sectional issues and findings are properly channelled towards the main function, has prevented much from appearing in the press. By the time the report is published and goes forward to the participating governments, the public will have forgotten June '72 in Stockholm and the white paper will become an obligatory international law book to restrain political and business powers everytime the masses scream green. That most New Zealanders knew anything was going on at all was by courtesy of the French nuclear teats which enabled our Mr Macintyre with his newly extended portfolio to pack a pistol rather than a peashooter with his pyjamas.

New Zealand, sitting at the end of the industrial limb and washed by westerlies, would hardly appear to be an offender. But per capita, New Zealanders are every bit as good at making a mess of their environment as any other free swinging democracy. An overnight calm coupled with an atmospherical temperature inversion will turn Wellington's Hutt Valley into a keen competitor to race Christchurch's Hornby and Auckland's Otahuhu in having the best reduced visibility for that day. But during my recent three weeks in the Kermadecs, I automatically ducked nightly to an obstruction that was 100 million light years overhead. Not once could I ignore the brilliance of this heavenly display as it transmitted its light through a clean atmosphere. Campbell, equally blameless in the pollution problem, will return a similar showing when the westerlies decrease sufficiently so that the southern ocean can claim back its airborne salt.

That the national example might well be similar in the future could be assisted by weight from appreciative expedition members - lads who have smelt and seen a better place. Mr Macintyre's earlier statement that the full implementing of an industrial antipollution scheme would lower the standard of living, was perhaps a tentative statement when he arrived staffless in his new office, and I think would be a statement pointing at future material discomfort rather than environmental discouragement. I would hesitate however, to say that this would be the case. No sensible government would allow a lowering of standards, but certainly a stabilisation of standards at a time when consumer products are constantly raising these levels.

If every New Zealander could be taken on" a trip around the rocks" to see how it was naturally, they might well tolerate it the way it is domestically, while the experts adjust it industrially.

AN UNUSUAL HONOUR:

John Jerningham in his ‘Evening Post’ column, recently revealed that those publications hiding within their postal wrappers that are emblazoned with the protective wording ‘registered at the GPO Wellington,' are actually stealing a march and oiling for recognition from the Government Printing Office. Whether or not Mr Shearer is prepared to take under his wing the hundreds of national organisations which wish to express their thoughts and talk in print, is not known. For my subscription, I hope I am not offending the CPM of the POHQ by siding with the GPO - an office which has won world-wide recognition with its varied printed, and frequently highly sophisticated products over the years.

THE 5TH ANNUAL FILM EVENING:

was a pleasing success some 90 folk attending the function in the Lecture Hall of the Meteorological Service's head office at Kelburn. The films shown were 'Chatham Islands' (1968), ‘Adams Island' (Auckland Islands, 1966), the new NZBC documentary on Campbell Island, 'Pitcairn People' (BP 1963), and 'Once Upon an Island' (Raoul Island, 1970). To ease the pressure on the supper girls in the cafeteria, 'Fifty Four - Forty South' (Campbell Island NFU 1950) was also shown, but it only delayed the crush, as nearly everyone elected to stop back and see that too.

Apart from the modern generation of expeditional trippers, it was fine to have along coast watchers Laurie Pollock and Norm Trustrum (Campbell and Auckland Islands), and Les Hack (Raoul and Pitcairn Islands), as well as MOW inspectors Bill Hughes and Keith Masters. Supporting the medical school were Dr Janet Brown and Sister Jenkins, and Brian Bell was along to wave the Wildlife flag. The committee records its thanks here to projectionist Tony Bromley, the girls who prepared and supplied the supper , Margaret Young of the NFL for her thoughfulness and co-operation and the Director of the NZMS for permission to use such excellent facilities.

THE VINTAGE YEARS:

Recently I have received fair comment from two or three members for more contemporary articles within the bulletin. I have always been well aware of this deficiency since taking over editorship, but it is not an easy request to fulfil. Frequent pleas within these pages for such contributions has drawn a blank to date and it would surely be realised that the last 150 years contains more scope than the last five. Even the quarterly island reports are the devil to compile having to rely on RT skeds which are time consuming and exhausting, and which frequently have to be abandoned before completion due to the bogey of atmospherics. A constant watch is kept on possible avenues for stories such as this quarter's 1970 account of Lynton Diggle’s spear fishing in the Kermadecs and the previous issue's 1970 Campbell Island sheep eradication programme by Brian Bell. Coming up from Campbell's next servicing will be three separate tales from lads in residence down there now. Contemporary articles are tomorrow's most accurate historical accounts, so we need all we can lay our hands on - now.

The Editor.

••••••••••••••••••••

THIS QUARTER'S CONTRIBUTIONS:

There is the useful filling of another gap in the history of Campbell and the adjacent sub-antarctic islands with Ian Kerr's sixth historical installment. The years of 1840 to 1880 certainly saw quite a bit of traffic pass in and out of Perseverance Harbour, far greater than I had realised for sealing activities during this period had appeared to me to be a bit of a 'dead duck'. But there they were, those hardy, smelly little sailors still rushing about in the tussock and hastening the advent of the Seals Fisheries Protection Act which came down on their heads in 1878. Ian takes us up to the threshold of another interesting era - that of the New Zealand Government putting her own ships to sea to patrol our outlying islands. As a companion piece to this latter period, Dr R.A. Falla will be providing an article in the near future on these gallant little vessels which will tie up all the facts you ever wanted to know about them.

Sitting idly in the sun recently on the wharf which projects into Lake Rotorua, I recognised the urgent action which propels Lynton Diggle, forcing him to trot under his usual burden of accumulators, tripod and battered 16 mm movie camera. He braked hard alongside me and cussed his lot - a motley collection of beautiful people from America, slowed to a crawl by the evaporation of last night's life-giving fluids that had made them such a fine action group so few hours before. How the film came out, I guess we will never know, but I was into Lynton in a flash for a story about his 1970 diving efforts in the Kermadecs. Lynton only had time to hack out an address of a buddy up in Whangarei and he was gone. So Wade Doak sent down to me the required article which appeared not so long ago in his magazine ‘Dive’, a neat little bulletin dedicated to all those that must go under the waves rather than over them. Wade had a crack at getting after 'those Kermadec Bass', but didn't count on a tropical cyclone which forced him back to port again. It’s a very small reprieve for those monsters of the Kermadec Deep however - Wade's trigger finger, like Lynton's, doesn't like delays.

And Alf Bacon's second trip to Raoul (1926-7) is recorded within too. Most of us vaguely know of this ill-fated venture to inspect and see what could be done with J.C. Cameron's 275 acre freehold property on Raoul 's north coast. Poor Charley slept on peacefully for 35 years under the Norfolks down on the farm until Geoff and I in 1962, erected a two ton memorial of beach rock on his chest to which Brian added an exquisite little cross of solid brass that he had cut and filed in his workshop. One wonders what developments would have been made on the freehold if Charley Parker had not come to such an untimely end. Whatever may have been created it would hardly have equaled Alf’s and Bruce's efforts in making ‘Baconsflat’ , Alf's haven of the mid-thirties, about which we shall learn in his concluding article in the next bulletin.

********************

REPORT FROM RAOUL ISLAND

Time slips by rapidly and we are into the last two months on Raoul Island. August has some highlight in store for us with a scheduled air-drop on the 23rd, with the eagerly awaited mail, parcels and odds and ends etc. The 25th or 26th will bring the arrival of the M.V. "Acheron" from Gisborne with a party of Wildlife, Forestry, Lands and Survey and D.S.I.R. Officers. The intention of these people is an all out assault on the noxious animals on Raoul Island, namely goats and cats. It is a closed season for Expedition members. They will be using 15 dogs and 600 traps to expedite this operation and they will be on the Station at least two months. We might be able to borrow an extra hand for annual servicing. Our shooting days are therefore, curtailed, just as well perhaps, as servicing is just around the corner.

A visit this quarter from the yacht "White Squall" from Tauranga, skippered by Peter Luxmore. They arrived on Queen's Birthday Weekend and bought with them welcome mail and one or two essential items that went astray with the Icebreaker at the mini servicing in March. The crew spent four days here and a party went out with them to Meyer Island on the Sunday for photography and fishing. An unexpected visit from our latest warship, Frigate, HMNZS "Canterbury" captained by Mike Faulls. She was on her maiden voyage to Lyttelton and steaming down from Pago Pago and decided to drop in and take our mail off. The Commanding Officer and Pilot brought "Wasp" in and we loaded her up with crates of oranges, 115 lb of porker and mail. The Commanding Officer and Pilot were shown over the Station and on behalf of the ship the Captain presented the ship's crest wall plaque for the gallery. The lads were pleased to be able to send mail out and the Postmaster was kept busy. We had 90 minutes notice. We were concreting down at Fishing Rock when the word came through. Panic - utter pandemonium – “Le Mans" start on truck with working crew running to catch transport. Believe it or not we made it with an hour to spare. The Navy were half an hour late destroying forever that legendary maxim "The Navy is always on time".

The fishing competition, in Kingfisher Stakes, the position is unchanged, but in the open competition the second in charge, Colin Wellington, was dethroned by Moki with 75 lb bass. "Don't know where all the big ones have got to".

Goat Competition to date; Moki 48, Enoch 44, this is for the second six monthly period which will be curtailed due to the arrival of shooters. There have been 346 animals destroyed to date; officer in charge 162, and Enoch 63.

Mid-winter's Day celebrated with exchange of subtle telegrams, bang-on dinner and a selection of wines, a swim in the Hume tank and a party to the wee hours. A mounted photograph was presented to Ron Urwin, the Chef, for services rendered during the year. All birthdays have now been accounted for with the usual hilarity and ribald remarks. Much ceremony and official photographs were taken at the cake cutting.

A most enjoyable year to date at Raoul and all wish the Association and all the participants a most enjoyable and successful reunion (have a few for us) and see you there next year.

Moki McGregor

REPORT FROM CAMPBELL ISLAND

With just over one month until servicing, our term on Campbell Island seems to have gone all too quickly.

The winter arrived in earnest in early April and well and truly “trenched” the myth that Campbell Island has little snow. For days on end show lying to sea level became a monotonous remark on the weather reports. While deep snow continued to build up on the higher peaks to the extent of mini glaciers developing on Mount Honey. June was a particularly vigorous month with gales being experienced on something like half of the days. The Station water supply, frequently frozen, became chronically low, from the effects of weeks of solid participation being blown off the roofs from which the water is normally collected.

Mid-winter's Day was celebrated in true Campbell Island style and all members of the Expedition including Mr Hogg, braved the gale force souwester with the temperature at 0 degrees Celsius and three inches of snow on the wharf for the traditional mid-winter's swim. For fear of sunburn the gaily coloured hats and sunglasses were worn and swimming attire ranged from very brief "grundies" to Met Observers, Dave Rowell and Shorty Wilkinson, wearing their girl-friends' two-piece bikinis with rolled up rugby socks for the bust improvement scheme. Hen Crompton decided his grey flannel feathers were more gracious. Bruce Mexted, our Cook, once again laid on a tremendous meal including some giant crabs collected the previous day. Fresh lettuce from Jazz Plumber's hothouse garden was a big feature and surely this is a record to have lettuce grown on Campbell Island for Mid-winter's Day.

July 21 was a big day when "R.N.Z.A.F. Orion" dropped in our first mail for six months with some fresh fruit and vegetables. Eight parachutes in containers were very successfully dropped at the new dropping zone between Tucker and Camp Cove, in spite of a very turbulent north-easterly blowing. Turbulence from Beeman Hill and Lyall Ridge had the big bird yawing on the first run and subsequent approaches were made up South East Harbour between Mount Honey and E Boule Peak rather than Perseverance Harbour. Within half an hour of the aircraft's departure the weather had closed in with murk within 100 feet and a really howling easterly. In spite of these events work has continued at a tremendous pace including improvements to the outside of the Station, Met interior decorating, with a large painting programme in both the Technical Building and Hostel. An ambitious plan to take a lot of the grunting out of annual servicing has been almost completed with the construction of two trailers capable of holding six 44 gallon diesel drums which can be towed by the tractor. A new steeper road leading from the wharf to the new diesel dump has also been made. Numerous other projects are nearing completion and we feel that we will certainly be leaving Campbell Island Station a much better place to live and work in.

With our term drawing to a close, we wish Graham Camfield and the 1972/73 Expedition all the best for their coming stay on Campbell Island. Four of our team are remaining on, Met. Observers, Hen Crompton, Shorty Wilkinson for the summer period. Bill Clark, the mechanic and Jazz Plumber, the Electronic Technician for the second year. These are really excellent men and we are sure that their conscientious work and their good humour will be as valuable to the new team as it was with our own.

August 25, 1972 Vince Sussmilch

*********************

MEMBERS COMMENT

The Shortest Day - but the Longest Night:

Quite a few of us knew that the coastwatchers of the sub-antarctic islands had continued their secretive practises into the post-war years and it was with some surprise and pleasure to me when I was called in as an observer to the Shortest Day Celebrations '72 by organiser Laurie Pollock. Tucked away in a comfortable city flat which was about twice as dry and warm as Port Ross, Carnley and Tucker combined, the annual nocturnal ritual of reversing the hemispheres was underway by 2000M.

In one corner was an exquisite scale model of Campbell Island large enough for the fingers to do the walking and built by Laurie in 1944 when he was leader at Campbell. A fine oil of the RNZN's first 'Endeavour’ hung from the wall and a table was piled high with old photographs, diaries and departmental pamphlets from the grim old 40's. A sea leopard's head came in for a night of teasing and a valuable selection of books on the sub-antarctic islands was on display. The ten members assembled soon knocked down the 30 year barrier and it was on.

An enormous steaming pot which might have come direct from the 'Ranui's' galley, was propelled in by Ron Balham, but the contents were far superior to the bilge matured food stocks of an auxiliary ketch. Judging by the appetites of these lads, I guessed they had not been back long from a quick swim around Adams Island or a slosh in the tussock at Courrejolles. The evening warmed to varied wartime ditties and a complex rum dance which continued until the Captain Morgan was cut. At midnight a brief appearance by Maida McTaggart was permitted, a person well known in the department over the years for handling some of the clerical work involving our islands.

Then came the hilarious quotes from diaries penned over three decades ago. Could it be that long? The effects of this crash course were beginning to work. What about five years? I think I may have been there myself at the time. Hell - I hope I get invited back again next year.

(And those happy faces in the photo on the centre page: Front left to right: Charlie Fleming, No.2 station (Carnley) 1942, now Director Geological Survey Division, DSIR; Johnny Douglas, radio operator, Carnley, 1942; George Bish, engineer ketch Ranui, Waterfall Inlet, 1944; Alan Paine, Carnley, 1943, leader No.1 station (Port Ross), 1944; Norm Trustrum, radio operator, No.3 station (Campbell), 1941; Laurie Pollock, Carnley, 1941, Port Ross, 1943, and leader Campbell, 1944.

Rear left to right:- Jim Trigger, Campbell, 1943; Ted Mitchell, Campbell 1941 and Ranui engineer 1943; Ron Balham, Port Ross 1943, Campbell 1944, met observer, now senior lecturer biology, Victoria University; Rodger Ingram Hunter - my cousin whom I have never met before, attended in his annual capacity as friend of the ‘watchers. Although physically poles apart, certain social trends we found were in common: endurance, capacity, etc. Pierre.)

_________________________

Eddie de Ste Croix (C61, 64, R68) reports in from Chathams that Bill Stuart (C69) turned on a contemporary Campbell Island slide evening at Rob Stanley's (C51, 55) during July; also in attendance were Eddie of course and Fred Buitenkamp (R64, 69).

__________________________

And from Bob Rae (Campbell many times over) and Lynne, now managing the Sailors' Home in Auckland's Quay Street East comes …. 'we have just been away on a month's leave and Lynne and I did a trip around the Islands for a couple of weeks then we went onto Australia for a further two weeks and in the course of our travels, we called in at Canberra where I contacted Tony Marsh (D.M.S.) and Lynne and I stayed with them for a couple of days. And Tony and I had a little Island Reunion of our own and we drank the health of all you chaps back there in Wellington. Tony said he had hoped to make the Reunion this year, but with his new position, he cannot as he has two big meetings to attend around that time, one in South Australia and the other up in Queensland. Tony is looking well and doing plenty of trout fishing, in fact we had a very good feed of trout. He also wishes to be remembered to all in New Zealand.

Last weekend Lynne and I went to Tokoroa to the Mid-Winter Scott Base - Campbell Reunion and we had quite a good turn out, a few well known names there: George Poppleton, Ian Johnson, Charlie Hough to name a few …. our best regards to all down there in Wellington.

___________________________

The usual mid-winter telegrams from your Association went out to the Islands again this year - one to Raoul asking for our sun back again, please and to Vince telling him to make full use of the longest night of the year by getting all the lads off to bed early.

********************

YESTERYEAR

Oh Lor'. Not the Loo'

26th Wednesday (April 1944, Tucker Camp): Very wet today. 110 points of rain have fallen in the last 24 hours and the creek is very high and still rising. The water is well over the bridge and is up to the lower board of the lavatory. In fact the outfit is threatened. Jack and I watched the water rising all afternoon and about 5 o'clock decided something should be done, for if the water kept on rising we would probably have no lav. by the morning. So during the height of the flood, working in about 2 feet of water over the bridge and sidewalk we tied the shack down with inch rope. However after we had completed this in the dark the creek steadied and began to drop. The house is surrounded by water during one of these floods. The dam is overflowing and the overflow channels can't take all the water, so some of it pours over the retaining wall and rushes madly down the side of the house. In the afternoon when the water was very high, Tub took a photo of me at the shack, sitting there with my thigh boots on. Let's hope it comes out.

27th Thursday: I permanently stayed the lavatory today with fencing wire and am now waiting for the next flood to see what it will do. Message from Awarua to No.2 (Carnley, Ed) asking for repeat of part of message sent earlier. Evidently list of requirements. Its possible that the ‘Ranui’ will not be going to No.2 before proceeding to NZ, or may even have left for NZ. We would all very much like to know. We are all looking forward very much to our mail, but of course the longer we have to wait the better it will be I suppose. Certainly if the ‘Ranui’ doesn't come till June, the last part of the year will go very quickly.

••••••••••••••••••••

SALARIES AND WAGES, 1972/3: :

| Officers in Charge | $5010 | |

| Electronics Technician | $4259 | |

| Telecom Technicians | $4259 | |

| Cooks | $3737 | |

| Mechanics | $3818 | |

| Maintenance Officer | $3339 | |

| Farmer | $4068 | |

| Ionosphere Observer | $4259 | |

| LOCATION ALLOWANCE | Raoul | Campbell |

| Single | $120 | $240 |

| Married | $240 | $360 |

| SPECIAL ALLOWANCE | $640 | $958 |

| (15/8/72) |

••••••••••••••••••••

Raoul's new leader Bob Ferguson who comes from Rotorua and Campbell's Graham Camfield from Ranglora, commenced medical training at Wellington's Public Hospital during mid-August.

Let it be known that every person living on Raoul Island at this moment is a member of the Campbell-Raoul Islands' Association. C'mon Campbell.

••••••••••••••••••••

THOSE KERMADEC BASS by Lynton Diggle

I 'm always deeply suspicious of a man who holds either a cigarette or a pipe in the centre of his mouth, (Lynton is well known for using the left-hand corner of his mouth, Ed), but this one, complete with beard, happened to be the skipper of H.M.N.Z.S. 'Endeavour'. We were approaching Curtis and Cheeseman in the Kermadec group and I wanted to go diving and as a civilian passenger one must go through the proper channels.

"John Moreland from the Dominion Museum, in Wellington, is most anxious to have samples of the marine life from here", I said to him, not knowing or caring if it was true.

“Mmmm, all in the cause of science I suppose", he said as he lowered his sextant (obviously no Omega on board).

"Oh yes Sir", I said, trying to be very convincing , and smiled.

"I'll fix it up with the Jimmy then", he said. He mumbled something else then turned away. ('cause everybody knows that the 'Jimmy' is 2IC on Navy boats).

You see I was on my way to make a film about Raoul Island in the Kermadecs, transport by courtesy of our Navy and I just happened to have my diving gear with me. Also on board were an odd assortment of wildlife characters, botanists, birdologists, palaentologists, the museum's taxidermist etc. They were catching a ride also to do some botanising and birdwatching on the southern group.

The Jimmy was seen, the cutter launched and I was off diving, with the might of the N.Z. Navy behind me. Curtis and Cheeseman (only a few hundred yards apart) are literally poised on the brink of the Kermadec Trench, plunging to a mind expanding 6,000 feet on one side and 32, 000 feet on the other. The curse of it though, was that I would only have a few minutes in the water while they looked for a suitable landing. So a quick spit around the mask and over I went. A big Kingy was beside me immediately - I shot it in the head and climbed back on board. The coxswain the RT operator and the engine hand goggled their eyes as I pulled in about a 70 lber. I had only been in about a minute and a half. The plant gatherers couldn't find a suitable landing with the rough conditions and the light was fading so they would try again in the morning.

A dinner, bed and breakfast later I was over the side again and paused to take in the sight. It was orgasmic. I could see 100 feet, no it must be around 150 feet. Monstrous kingies were around me again, but I was looking beyond to a huge school of Northern Kahawhai. It was about 50 feet to the bottom directly beside the cliffs, and the bottom was covered in huge boulders with cavernous openings under them. It sloped steeply into a twilight blue around 200 feet. To my right was a school of blue looking fish around 3-6 lbs that I'd never seen before and interspersed were the oft' talked about Kermadec yellow fish. They had been seen from the surface for some years in the Kermadecs, but had always avoided a line.

The taxidermist had pleaded with me to get one for Moreland. I fired while one was looking the other way and handed it up to my ever present cutter and attendant ratings, dutifully hovering near me. Back over again. Hell! I was excited by the visibility. (Eddy Davidson can keep his Kapiti Island). Damn it, there was a bass, a big one too and another. What a sight the bigger one was, would go between 80 - 160 lbs. I dived and got to at least 25 feet before clawing for the surface again. I was just too worked up to dive properly. 'Now, take it calmly, just try and relax", I told myself, "Easy breathing now down again". I thought of my friend and veteran diver, Bill Baldwin, who just has to be the most relaxed diver I ever see (and one of the deepest) in New Zealand. Slow leg movements; quick movements use oxygen. I reached level with the bass; it lumbered slowly away. I moved quietly with it. I'd have to go up soon - I fired, a desperation shot, but it hit and held.

Pandemonium. I made for the surface, the bass for the cave. I pulled and away fell the spear. Damn. Damn. Well what's a bass anyway. Now another lumbered across the bottom - the visibility was still orgasmic. This one looked even bigger, but was mottled brown. I dived but it simply swam away ….. now, there a got to be some trick to this.

"We've got to go back to the ship now"1 yelled the coxswain. Oh, no, how could he. I'd only had about half an hour. "Hang on a minute”, I said. At least I can still shoot kingies, I thought as I picked out a handy one from the ever present school. More goggling of eyes from the crew as we made our way back to the ship. I just stared at the two little islands of Curtis and Cheeseman with a kind of glazed look. Only a spearfisherman could understand how I felt. Fortunately there was a stop to be made at Macauley Island where the five gentlemen of science were to camp while we went on to Raoul.

"I'm a diver too", said one of the ratings as he proudly showed me his Navy issue Moray suit and Atlas handspear. "Would you mind if I come in with you today?" "Be delighted" I said, only too pleased to have company and someone to verify that I wasn’t suffering hallucinations over these bass. Stores and camping gear were being transferred to the landing party's little runabout while Keith, the Naval guy and I readied ourselves. "All set?" He nodded, picked up his handspear and over we went. Much shallower water here, around 40 feet, but still great visibility. "Let's be honest", I said, 'there's a lot of sharks around the Kermadecs, so look behind as often as you look ahead, and keep in sight of me".

A turtle swam near, the first I had ever seen underwater. I aimed at its neck - I missed - no wonder I can't make the Reefcombers' National team. A black bass appeared on the bottom, right in the open. I was getting blase about the Kermadecs now and was diving like a champ, all relaxed. This one paused just a second too long and I got a good snot away. It certainly wasn't the monster like I'd seen at Cheeseman, but still all bass. The cutter was still playing storekeeper, so I had the battle all on my own. "Give me your handspear", I said to Keith. Down the line I went and one shot with the big spronger head and it was all over. Forty-one pounds of Kermadec bass was gently eased into the cutter and we were back in the water. I motioned to Keith to look behind him. Trailing behind a following and inquisitive kingfish, was about a 6 - 7 foot Bronze Whaler. Keith moved closer to me, but I dived below him, gun outstretched and hung there, eyes firmly on the shark. I was too fascinated to be frightened. There were three pilot fish leading him along. It turned in slow motion and quietly moved towards me. It kept coming and coming. It's got to turn soon, I thought. No more than 6 feet away it did. I fired, confident of good holding shot. Holding shot be damned, the spear hit with a thud and fell straight away. It was like hitting a brick wall. It moved off with an electrifying rush, leaving me rather puzzled but determined to attend to what I knew was a not too sharp spear tip.

I moved into deeper and more broken territory looking for a bigger bass and I found it standing guard over a cave entrance like a giant mastiff outside his kennel. I hyperventilated and dived. It was beautiful. I was feeling great, the water was warm and I was sinking gently onto a good 80 pounder. I aimed for its spine from above. The fish seemed to stagger under the impact and I made for the top. What a dead weight on the line. I had to keep him out of that cave. I had him half way to the surface. I was feeling elated already. It was as good as in the boat. Suddenly he came back to life and lunged down and into the cave thrashing sand and rock. I pulled, but seemed to only succeed in pulling myself under rather than the fish up. I finally pulled him out from his kennel and the battle was on again. However, it was all short-lived as I felt the tell-tale ease or pressure and there was my spear dangling in mid water. He was lost.

What a magnificent fish. What a magnificent place. What a magnificent sport. I can't help but feel that I was the first to spearfish at Curtis, Cheeseman and Macauley Islands. Who's going to be second. (Footnote - the Kermadecs are N.Z. Territory (in the Hobson Electorate) and that makes them eligible for N.Z. spearfishing records. I don't care what anybody says ….. ANYBODY.)

Originally printed in 'Dive' magazine, by Wade Doak. ‘DIVE ‘ Vol. 10, No.5.)

•••••••••••••••••••••

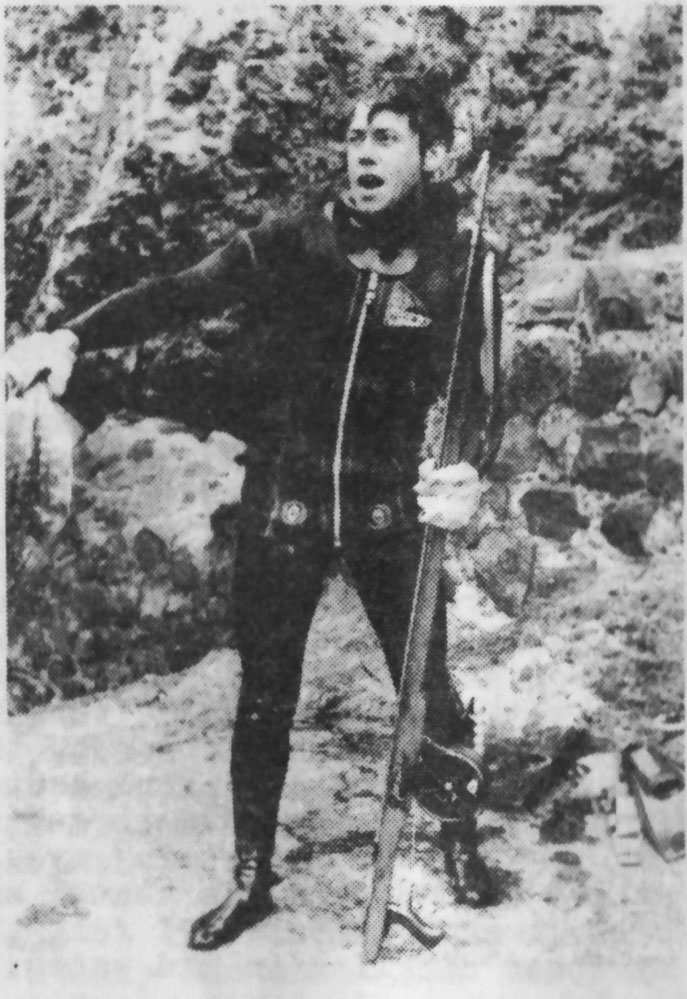

THE YELLOW DRUMMER BOY

Lynton Diggle (NFU) on the Boat Cove landing, 1970, was

responsible for bringing the first yellow drummer fish tp the

surface for human inspection. (photo: P Ingram, 1970)

The tranquil beauty of the Boat Cove road as it traverses the side of

Judith before the Moumoukai loop. (photo: A Gardiner, 1944)

Part of the Cape Expedition (1941-44) coast watchers on night shift at

Laurie Pollock's Wellington flat celebrating 1972's shorest day.

(photo: P Ingram, 1972)

The Heard Island Corinthian Bay camp opens its door to Mawson's shore party after a quarter century closure. Nine days were spent at Heard (Nov/Dec 1929) before proceeding to the Antarctic. Robert Falla is seen passing the flag with the snowy pedestal of Big Ben in the background, but Ritchie Simmers never made it ashore as he was required for permanent weather watch on board the 'Discovery'. (photo: BANZARE, 1929)

............................................

CHAPTER 6

COMMERCE AGAIN : REVIVAL OF SEALING

The record for the twenty years following Ross' visit in 1840 is almost a complete blank. Some of the shore whaling stations established in New Zealand in the thirties were still flourishing in the forties and the men sometimes went after seals in the off season. Mostly these expeditions were to the Sounds and along the west coast but occasionally they were to one or other of the southern islands. We have knowledge of only one such venture, by the 'Scotia' (Ward) to the Auckland Islands in the summer of 1842-43. It has been stated that the ‘Scotia’ also visited Campbell Island at this time.

Sometime before 1864 an unknown amateur geologist must have explored the island for we learn that a Sydney draper by the name of Charles Sarpy had reason to believe in the existence there of a mine of argentiferous tin. Sarpy's informant may have been just a teller of tales, but if so, he must have been convincing for Sarpy was able, in turn, to persuade an acquaintance, F.E. Raynal to undertake an expedtion. Raynal was a Frenchman who had lived in Australia for a good many years and who had recently been working as a miner in New South Wales. Plans went quickly forward : a suitable schooner, the "Grafton", was found in three weeks; Thomas Musgrave, American nephew of an associate of Sarpy's, joined the venture as Captain on one quarter share of the profits; the Frenchman and the American were joined by two sailors, a Scot and a Norwegian; and a Portuguese cook completed the crew. If the tin mine was not found or it proved unprofitable, it was intended to engage in seal hunting. After making arrangements for a search to be made if they had not returned in four months, the party left Sydney on 12 November 1863.

Campbell Island was reached on 2 December and the anchor was dropped in what was probably Perseverance Harbour; Raynal called it Abraham's Bosom. Raynal unfortunately fell ill almost immediately and was unable to leave the schooner for nearly a month, but Musgrave and the others searched the island thoroughly for the tin. They searched in vain and their seal hunting was little more successful; in four weeks they captured only five seals. One of these was "a very fat old fellow" who yielded 150 litres of oil. On 29 December they gave up all hope of finding the mine and set sail for the Auckland Islands in the hope of finding seals more plentiful there.

They entered Carnley Harbour, in the Auckland Islands, on New Year's Day of 1864 but, in the teeth of a gale, a safe anchorage could not be reached. The storm continued throughout the second and, one anchor cable snapping, there was little hope of saving the ship. Her position was such that she could not ship the other anchor and have any chance of making her way out of the harbour. In the early hours of the third the "Grafton" was driven ashore and soon became a total wreck. Both Musgrave and Raynal published accounts of the party's struggles to survive over the next twenty months. Finally, they succeeded in making a boat and three of them sailed it to Stewart Island whence the "Flying Scud" was sent to rescue the other two. Musgrave, who accompanied the Rescuers, thought he saw smoke rising from the northern part of the island, not from a fire started by his own shipmates, and then the body of a man not long dead was found at Port Ross.

On his return to Melbourne, Musgrave voiced his fear that there were other castaways an the islands and the Victorian Government wasted not time in sending H.M.C.S. ''Victoria" under Captain Norman to search the islands. No castaways were found although, in fact, the survivors of the crew of the "Invercauld" had lived on the island for twelve months of the time the "Grafton's" crew was there. They had been rescued in May 1865 by the Portuguese ship "Julian".

After searching the Auckland Islands the “Victoria" sailed for Campbell Island and reached there on 28 October 1865. Captan Norman reported that Musgrave's local knowledge enabled him to enter Perseverance Harbour with perfect safety and so obtain shelter from a gale that was threatening. The gale restricted activities the next day, but on the thirtieth, three parties set out to ascend the hills near the harbour. Excellent views were obtained but no signs were seen of any wrecks or of anyone having lived on the island in the recent past. Norman described the difficulties of travel on the island, the treacherous holes hidden by the tussock and: "Some of the points could be reached only by climbing barefooted up precipitous rocks".

Doctor Chambres planted some oak, elm and ash trees; and a boar, two sows, three guinea fowl and three geese were liberated. A sign-board was erected on the point and secured to it was a bottle containing a letter listing the stock and requesting that it be given all possible protection. All that day, guns were fired at intervals and, on the next day, the ship moved round to North East Harbour. Here, too, there was no sign of the presence of either man or animal and Norman left Campbell Island satisfied there were no castaways there. Musgrave was sure no one had been there since his visit two years before.

The wrecks of the "Grafton" and of the "Invercauld" were followed in 1866 by the loss of the "General Grant" also at Auckland Island. After eighteen months ten of the fourteen survivors were rescued by the whaling brig "Amherst" and taken to Bluff. The other four had set out nearly a year before in one of the "General Grant's" boats to attempt to reach New Zealand. As nothing had been heard of them, the Provincial Government of Southland sent the "Amherst" out again to search the other islands. A member of the Government, Mr H. Armstrong, accompanied her.

The captain of the "Amherst" at this time was "Paddy" Gilroy who later became almost a legendary figure. Some of his exploits in the whaler Chance have been vividly described by Bullen in his book, The Cruise of the Cachalot.

They left Bluff Harbour on 25 January 1868 and, after searching and provisioning the Auckland Islands, they bore up to Perseverance Harbour on 14 February. Before the brig could enter, a westerly gale sprang up and continued with little respite for the next five days. All this time the "Amherst" was hove to but held her own well, never losing sight of the island. On the nineteenth they managed to make the harbour, but for another four days the wind blew furiously and all they achieved was the landing of some goats, "two billies and three nannies". On the twenty-fourth the conditions being better; they put two boars , three sows, a case of provisions and clothing and other equipment in the boats and took them to the head of the harbour. They also had a large spar in tow, ("Captain Gilroy being very seriously determined to leave substantial evidence of the brig's visit"). This was erected about 50 yards from the Victoria's mark, two boards were fixed to the top, and the provision case and a spade were left at its foot.

Some 20 years afterwards, Armstrong wrote an account of his trip for The Leisure Hour. In this article he said that near the hand of Perseverance Harbour they found six graves and alongside them, the skeleton of a man. He did not mention this in his official report written at the time. A thorough search for castaways was made during two days. None was found but on the beach at Monumental Harbour (North West Bay), were lying several spars and planks, all very old, and a metaled gangway rail which looked fresh.

One of the spars was erected and a letter indicating the position of the depot was placed in a bottle at its foot. At North East Harbour, to which a party travelled overland, climbing Mt Lyall on the way, another letter was left by a cairn of stones. Armstrong remarked that there were no indications of copper. He also reported that they found no traces of the pigs, fowls and geese landed, or of the trees planted by Captain Norman a little over two years before.

Concerned about these tragedies the central Government sought the assistance of several of the Australian State Governments in establishing and maintaining permanent depots on the islands. Victoria agreed and two other States offered limited help, but little was done. The "Amherst" had left depots of a sort but the Marine Board had no suitable vessel to attend to their maintenance. Nevertheless in the next decade ships of the Royal Navy made occasional visits of inspection. We have references to calls at Campbell Island by H.M.S. "Cossack" in February 1873, "Blanche", "Saphhire", "Nympha" and "Emerald" in 1874, 1877, 1878 and 1879, respectively. The navigators of the “Blanche" and "Cossack" supplied reports and surveys to supplement Admiralty descriptions and charts of the islands.

In the seventies there was a revival of the whaling trade baaed on Port Chalmers, Bluff and Stewart Island. The Otago Provincial Council sought to encourage it by offering a bonus of 500 pounds to the first ship to bring in 100 tons of oil. The first to lay claim to the bonus was George Printz who had sailed to the southern isles in the "Scotia" thirty years before. His vessel, the "Sarah Pile" had brought in 16 1/2 tons of oil, 1200 lbs of whalebone and some sealskins in October 1873, but his claim was somewhat premature. The bonus was only being talked about at this stage. The two principal contenders were Sam Nichol's "Chance" and William Elder's "Splendid". Some of the ships were small, for example the "Chance's" tonnage was but 82, and one at least had to spend several weeks sheltering at Campbell Island.

About the same time, too, sealing about Foveaux Strait and the Sounds took on a new lease of life. Quite early in the decade it is probable that some of the sealers ventured southward. On 29 October 1872, the 17 ton schooner "Nancy" was reported by The Southland News as returned from a sealing cruise at the Auckland and Campbell Islands with 150 skins and 1/2 ton of oil. There seemed however, to be some doubt about this as The Southland Times reported the "Nancy" as from the West Coast and Stewart Island.

In 1877, an enterprising Dunedin firm determined to have a share of the trade. This was Thomson Brothers and their vessel was the schooner "Benclough". With J.I. Thomson on board she sailed on 28 March, reached Campbell Island on 6 April and anchored in North East Harbour. During the next ten weeks the crew scoured the island for seals. They reported that both fur and hair seals were plentiful but were exceedingly wary, and most of them haunted places that were quite inaccessible. Their bag was only about 90 skins. A few sheep, believed to have been left by the “Vire", were seen and appeared to be suffering from footrot. The provision depot was reported to be in good order and wreckage was seen in North West Bay but could not be identified. This was, in doubt, the same as that seen by Armstrong in 1868.

In May, a tsunami or earthquake wave caused alarm and some damage. It was reported to have been ten to twelve feet above normal high water and washed away a number of casks and boat gear. Most of this, however, was recovered.

Very shortly after leaving Campbell Island the "Benclough" encountered a severe storm and lost her jibboom, topmast and the two sealing boats. On her next trip, in December, this time to Macquarie Island, she was wrecked.

In the same decade, Elder established a gang on Macquarie Island and maintained communication with them with the Port Chalmers schooner "Friendship". Elder's interest was later transferred to Hatch of Invercargill and the exploitation of Macquarie Island's seal and penguin rookeries continued almost unbroken for about 40 years.

The "Friendship" called sometimes at Campbell and Auckland Islands, no doubt to pick up a few extra seals. On one such call Campbell Island late in 1879 she found a gang of seven men left there by the Invercargill schooner "Awarua" in July. They had apparently had little success or, at any rate, had exhausted the island's possibilities, for the "Friendship" took them up to Auckland Island to join the “Awarua’s” other gang. This gang had, however, disappeared and although the Campbell Island men searched diligently and Captain Drew on his return in the "Awarua" also searched, no trace of the men was ever found.

In July 1880, the "Friendship" again called at Campbell Island and this time met there the 45 ton schooner "Alert" belonging to Messrs Henderson and Thompson of Invercargill. The two masters, Wilson and Rattray, examined the depots and found them in a state of decay; all the provisions had been taken away and what clothing was left was of little use. The "Alert" remained at Campbell Island for about three weeks and then returned to Bluff, leaving a sealing gang behind. Two more gangs were taken out to the Bounty and Antipodes Islands in August and September and, in October, the "Alert" visited Campbell Island again. All the gangs were brought home in November but this comparatively large scale effort does not seem to have met with much success.

The Seals Fisheries Protection Act, 1878, provided that "no person shall hunt, catch or attempt to catch or kill seals between … the first day of October and the first day of June following, both inclusive". It was further provided that the Governor, by Order-in-Council, could vary or extend the closed season up to three years at a time. The penalties were forfeiture of seals found, fine not exceeding 50 pounds and additionally up to ten pounds for each seal taken. In March 1881 Captain Grey, in command of the S.S. "Stella" visited the Snares and Auckland Islands. His report to the Secretary for Marine, tabled in both Houses of Parliament, related that men had been surprised working at the Snares. No evidence that they had been killing seals was found, only the skins of birds, but Grey was convinced, by their evident trepidation, that they had been sealing in the closed. The report went on to state that there were far fewer seals about the New Zealand coasts and islands than in the previous year and that the writer was certain poachers were active in the closed season. As a result of this report and some questions about it in the House three steps were taken for the better protection of seals. Under the 1878 Act a closed season extending from 1 November 1881 to 1 June 1884, was declared. Second, the Commodore of the Australasian Station was asked and agreed to instruct his commanders to report any infringements of the law that they might observe. Finally, it was decided to acquire and fit out a suitable vessel to make regular, frequent trips of inspection to the islands.

The island's history now entered on a new phase. For the next forty-five years New Zealand Government vessels and ships of the Royal Navy paid regular visits to the sub-antarctic islands. The events of these years will occupy the next three installments.

********************

A JOURNAL OF EVENTS, PART TWO by Alfred Bacon

In this second article we learn of Alf's return to Raoul Island in the 1920s. Now at an age of 54, he had not seen the island for 36 years. The dream had become a reality on the 5th November, 1926, when the NZGS 'Hinemoa' off-loaded himself, Charley Parker and Jim Ashworth at Denham Bay. Parker had purchased the 275 acre freehold property on the north coast from a J.C. Cameron, who had earlier paid the original owner, Thomas Bell, a sum of $100 for it in 1902.

THE WANDERER'S RETURN.

"The Government steamer ‘Hinemoa’ took us there, with a lot of gear and stores, but our luck was out as regards landing. The sea on the North side where we wanted to land was too rough, so the captain said. So they landed us and all our stuff on the 5th November 1926, on the beach in Denham Bay, with a 400 gallon tank, 26 sheets of 8 foot iron, some timber, cases, barrels, bags, 4 hens and a rooster, two fox-terriers, rifles and what not, all strewn along the beach. It took three large boat loads, the last boat landing in darkness. By the time the stuff was carried up out of the way of the waves, we were fit to lay down. So we got our blankets out, made a hole in the sand for our hips, leaned some sheets of iron on cases and turned in under them. The steamer then left us on that lonely island to our own resources. The 'Wideawake' gull as they are called, but really a tern, a black and white sea bird with a swallow tail, were in thousands flying just overhead , screaming all night, so we had little or no sleep. Next morning we carried the fowls about a mile along the beach, to a lagoon that was a lake when I was there first, made a run with the wire-netting we had brought with us and left them there. We then went back and pitched the tent, got all our stores inside and made everything secure as we thought. But in the night a storm arose from the S.E. and, we had to get out of bed to keep our tent from blowing away. More stakes were driven into the sand, heavy pieces of drift-wood were piled on the ropes, as the sand did not hold very well, and after a lot of work we got back into the blankets, but not to sleep as we expected the tent to go with the gale. However it hung on and the next morning was fine. Parker and I tried to make a track up the thousand foot cliff to carry our things over to the other side where Bell's old place was and where we were going to camp for the future.

Bell's old track had slipped away, so we had to find another place to get up and it was a job too. We managed to reach the top after a lot of risks and then came another hard task to go down through the bush and thick fern well over our heads. Not remembering the track (and it being overgrown), we went down the wrong ridge, which brought us far too much towards the West and had to tramp through buffalo grass up to our middles to get to the site. Not being able to get a drink all the way over, we were very thirsty and even though we found a small concrete tank which was let into the ground, we didn't drink from it as a matter of caution. Oranges and bananas were plentiful so we had our fill of them. We went down to the beach, about 200 feet below and found a fine boat that had been left there by some of the Bell family that had gone back to New Zealand in 1910. The boat had two holes in her, for she had evidently had been on the rocks. Our bed was in the buffalo grass that night, a draughty one too, and having only a singlet to cover our backs, we were cold and had no sleep. Next morning was fine and we went back to the camp in the Bay. I remembered where the track left the old homestead and followed it right over. The following day the three of us started to carry our belongings over the climb of 1500 feet and down through the bush. As we went we made the track better by slashing some of the undergrowth down, which took quite a while and darkness came on us before we knew where we were - and to make matters worse, we had once again gone down the wrong ridge, having to climb to back as it terminated in an abrupt drop of some hundreds of feet. By the time we got to the track, it was dark and impossible to see our way, so we had to put the night in on a narrow ridge with a large tent for a covering. At daylight we made tracks for the place that was going to be our future home. There was nothing left of the Bell's dwelling, which had been a thatched house, and the place was all grown over with a dense growth of weeds. We spent the rest of the day making camp and getting ourselves comfortable, bringing more stores over the following day . The "Wide-awakes" were laying on the beach in hundreds so we gathered couple of dozen eggs, cooked them and found them good, but it took six to satisfy each man.

So the work went on clearing land for cropping, hunting wild goats for meat, fishing, building our house out of poles and thatching with nikau palm fronds and carrying in banana bunches. We split slabs out of the ‘Wairuna’s’ masts - a boat that was blown up by the German raider ‘Wolf’ in the First World War while awaiting any ship that might come along with coal - for the floor in the whare. According to the report of the ‘Wolf’s’ stay at Sunday Island, she sank the ‘Wairuna' and one other boat besides - the schooner 'Winslow’. The men were taken off both boats and were allowed to go free on board the ‘Wolf’. Two men jumped overboard in the night, thinking they may be able to communicate with any vessel that might be passing, but they were never heard of again; evidently the sharks got them, or they may have been dashed on the rocks.

After a few months of hard work we got the whare finished and quite a lot of land cleared and put into crops. The boat that we found when we first came over the hills had to be repaired, and to do that some 4" x 1/4" had to be got from somewhere. Of course there was nothing, so we went over to the Bay to get a 12” x 2" kauri plank that we brought with us from Auckland, carried it on our backs catching the branches of trees as we went - and after a lot of trouble the boat got finished. Then came the job to launch it and to go through the surf with two men that had never rowed in a boat in their lives. After a lot of explaining the hows, when and what-fors, I reckoned they were educated sufficiently to tackle a trip around the island to get a load that was still over there. So one day we had a try, and how we got out through the surf, I will never know. Jim's oar came out of the rowlock, Charley kept on pulling and before I noticed, the boat was broadside on in the middle of the surf. I had the steer oar and just had time to pull the boat around head on to a great wave that was just going to break. The boat shot half-way out of the water by mounting the wave and came down on the back with a bang. My two mates thought she had hit the bottom, but that was well below us. We got through - but with the scare and the rough passage, Jim almost collapsed - in fact he became useless and I had to pull with one hand and bale the boat with the other, as she leaked very much having been up on the bank for about twelve years. Besides the two patches I had put into her were not too tight. Still we kept on our course, but my arms and back suffered. Seven miles of that was enough for me, especially in a big swell that was running. When we got to the other side of the island the surf there was fairly small, being only one break on a very steep beach. We landed alright but Jim not being able to row back, we decided to pull the boat up out of the way of the waves and go back over the mountain with a backload of stores. A block and tackle we had in the Bay was used to pull the boat up.

Some time after we made another attempt to bring a boatload of stuff around, so we walked over, launched the boat, loaded, and pulled through the surf, but the boat being too weighty with the load, got swamped. Our things were well packed and very little got wet. Later on again we made another trip, and met with disaster again, for the surf on the north side had got up by the time we arrived and coming through, three great waves chased us in and the little boat beached after tearing in on the crest of a wave, but those following broke into the boat and filled her up, as others put her broadside on and turned her upside down. Jim got a blow on the head from the gunwale as she turned over, Charley was floundering around in the surf trying to secure an oar and myself came off with only a ducking as I had experiences like it before. All our things were washing up and down the beach, but nothing was lost.

Quite a lot of stores were still in the Bay but before we could go again Charley ran a fern stalk into his finger while clearing out a gulley to plant bananas. The day after he became ill and for two days he suffered agony, with lock-jaw finally setting in. He died at three in the morning (23rd March, 1927, Ed) with tetanus, and we buried him between two rows of Norfolk Island pines planted by the Bells fifty years before, where he had requested to be buried before he died. Jim and I had a talk over the situation, as we had no tenure of the land, it being left to Charley's brother in England and we decided to leave at the first opportunity to try and buy the section when we got back to New Zealand. One week after Charley's death the Government steamer 'Hinemoa' called in to see how we were getting on. They lowered a boat and came as close into the rocks as they could with safety, to communicate with us, but the roar of the waves were deafening, which made hearing out of the question. I had learnt semaphore signalling, as I thought, but got it backwards out of the book; of course those in the boat could not understand, so came ashore to hear what we wanted, and when they did, we were told to get aboard straight away. Having a lot of stuff I valued, I asked the Mate to go out to the steamer and get six sailors to help carry the gear down to the beach. To get to our place we all had to go about a mile along the rocky beach and then climb the 200 foot cliff, and when the boys got there, they were more interested in the bananas, water-melons, pineapples and other fruits. The Captain got impatient and began to blow the fog horn, so I said, "The Captain seems to he in a hurry?" "Oh, let him go to hell", said the Boatswain and then started to again eat the fruit. That was just what I wanted. It gave me time to carry three loads down to the beach. Bye and bye, down came the mob with their loads and their hands full of fruit. The Mate was waiting at the boat and looking as sour as a shaddock when we got there. However, the boat was a 20 foot whale boat and took a good load, though she was down to within about four inches of the gunwale with ten men, six pups and their mother and our gear. I can tell you my heart was in my mouth going through that surf, not for myself, but for fear the things would get lost if the boat got capsized. We got aboard the ship and the Captain took Jim and me into his cabin and shouted whiskey, but it was not long before we were in our bunks , feeling a bit seasick as the steamer got on her way to Niue Island. She stayed there two days taking on copra and while there I went ashore among the natives whom I found very amusing. After leaving Niue, we went to Samoa to pick up seven lepers, staying another two days, and having a zither with me, I quite enjoyed myself with the Samoans because of their fondness of music. The lepers were taken aboard and we set sail for Magongi, the leper island, which is a fine one, the harbour being an old crater rather like a lake after passing through the reef which surrounds the island. From there we went to Fiji for a day and then steamed for journey's end at Auckland. After living in Auckland for a few months I advertised in the daily paper for a number of people to join an association for the purpose of obtaining the section on the island from Charley Parker's brother, who by then was in possession of it. Many people answered the advertisement, and I soon had enough to buy it.”

( to be concluded )

********************

BOOK REVIEW: THE WINNING OF AUSTRALIAN ANTARCTICA

Mawson’s B.A.N.Z.A.R.E. Voyages: 1929-31.

A. Grenfell Price, Angus & Robertson, 1962.

The history of the Antarctic Continent has yet to span two centuries, yet it is a massive and complex subject and really beyond the boundaries of our islandic thinking and reminiscing. Why such a book for inclusion within our pages then? There are several reasons.

Firstly the aim of the book reviews is to form a bibliography with time on the published accounts of the small oceanic outposts that are akin by climate and isolation to our own two islands which have been responsible for creating this Association. Sir Douglas Mawson's 1929-31 Expeditions encompassed three of these: Kerguelen , Heard and Macquarie Islands. Secondly, two Wellingtonians, well known to most of us, were chosen to accompany the energetic Mawson on this great adventure: Dr R.A. Falla (recently retired director of the Dominion Museum) went along as ornithologist, and Dr R.G. Simmers (recently retired director of the N.Z. Meteorological Service) carried the burden of meteorologist. Both men have had their names added to the geographical signposting of this vast white wilderness: Falla Bluff (Mac-Robertson Land) and Simmers Peaks (Enderby Land). Thirdly I think we should have a few ready references in our minds on the Antarctic, for there is a considerable historic “rub-off” here, which is part of the 1llumination of Campbell Island's past happenings. The preliminary section in this 200 page textbook is quite an adequate scene-setter in this respect.

The centre and major section contains Mawson's diaries, published for the first time under the clever guidance of Grenfell Price at Lady Mawson's request - an extensive project (when one considers the appendicies) that Sir Douglas never fitted into his half-century's work on the Antarctic. This section is really tough going in its diary format, but it has its advantages in revealing a little of the character of Mawson, as well as supplying a ‘it is happening now’ atmosphere. Unfortunately the book's excellent maps will not extend past the pages in which they are bound, so that the reader spends time in irritating delays until he has devised a system of markers which is always a poor substitute. A generous photographic section (57 photos) terminates the volume and it is worth popping into the Public Library if you are handy some time, just to go through this gallery.

Undoubtably the expedition period was a reasonable success. Mawson discovered, claimed (in the name of the Crown), and charted some 40 degrees of East/West coastline - an erratic black line which has only recently been hammered into its correct geographical shape. And the scientists dredged, chipped and shot their way through this frigid region to return a good specimen payload. But for most of the time, there was a unique backdrop to their activities. While Mawson gazed down on his new lands from the cockpit of his flimsy D.H. Moth the whalers clung to their -rotating look-outs in the search for the (then) abundant whale herds, both parties absorbed in their work practically on the same visual horizon. And the appearance of the comic 'Norvegia’ in virgin waters, dunking the wingtips of her Hansa-Brandenburg seaplane whenver she rolled, so heavily laden were her decks from a cargo of coal filched from a countryman just around the corner .

But my chief interest in the book lies with Mawson's return (25/11 - 3/12/'29) to Heard Island. The account is adequate and worthy for reference listing. In the past, I have reviewed three books on post-war expeditions to Heard ('The Sea and the Snow ', 'Twelve Came Back', and 'Fourteen Men ') and with any one of these providing the necessary mental background, Mawson's little party of scientists will become strangely alive and active as they move about the Corinthian Bay area. In fact I almost felt as though I was having visitors. The fascinating Kerguelen Island (12- 24/11 129 & 8/2 - 2/3/130) is given similar treatment and brief mention of the Crozet Isles (2- 4/11/1.29) is fortunately supported by two photographs at book's end.

It is interesting to note that Mawson divides the Antarctic Expeditions and subsequent explorations into two sections: the ‘Heroic Era' which terminated with the death of Shackleton at South Georgia, and the ‘Mechanical Era' which surges ahead today. I would have thought the 'Heroic Era' might have been extended when one considers the ‘Norvegia' of the '30's or the 'Wyatt Earp' of the '40's. But the impact of the 'Mechanical Era' must surely be revealed in a recent photograph seen of a station-wagon pulled into the kerb of downtown McMurdo. For the sake of the Tourist and his Kodachrome, let us hope that a huskey is earmarked for stuffing and a pair of cross-country hickories have been conveniently left behind on the ice.

********************

A STEREOPHONIC ICEBERG FOR THE LOUNGE:

Vaughan Williams: SINFONIA ANTARTICA.

Conducted by Sir Adrian Boult with the London Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra.

EHI for WRC: STZ 1091 (1970).

With a notable national contribution to scientific work in Antarctica and a seasonal reminder of the massive American 'Operation Deepfreeze', I sometimes wonder why the ‘sinfonia' does not get a more frequent diamond-tip dusting by the NZBC. Surely its appeal would lie deeply with New Zealanders - yet in the recent years that I have become a regular listener to the YA’s concert and YC's evening programmes - I can only recall having heard it the once. Perhaps EMI’s recent pressing for World Record Club will bring it to the fore. Certainly Dr E.A. Wilson's crayon and wash ‘Mount Erebus from Hut Point', which almost fills the dust cover, will be responsible for adding the recording to a few more private libraries. Shops have been generous with its display recently and the Wellington Public Library has now added it to their collection (WLP Ste 5024).

Vaughan Williams completed the ‘Sinfonia’ (so called as it had no real place in his numbered symphonies) in his 80th year, having it first presented at Manchester in 1953 by the Halle Orchestra. Four of the five movements came from a reshaping and expansion of themes he had used in 1947 with the Ealing Studio's film 'Scott of the Antarctic'. (Note the centre 'c' is dropped in VW’s title). Perhaps not a symphony of massive development, it is undoubtably a clever piece of musical tinkering and blending which must have been partially inspired by the modern processes of cinematography, alongside which he had to work so closely in 1947.

The PRELUDE (9:24) is virtually a complete miniature symphony in itself. In this movement the listener first experiences the haunting vacuum created by the Philharmonic's female section of the choir - a wordless siren-song coupled with an ingeniously toothy wind machine. A muted trumpet fanfare introduces the Expedition's pin-prick size to the icy arena and a very full orchestra finally forces a high note of human endeavour to end the movement. The SCHERZO (5:23) finds an early place, as its lighthearted wandering passages depict a healthy activity in the sailing of the Expedition and introduction to the water-borne creatures of the Antarctic region. LANDSCAPE (11:40) is obviously the workhorse for the symphony. Opening with a soft aurora-like brilliance it works its way to a thunderclap climax of crashing organ chords which could stun the unprepared imprisoned in a stereophonic headset. There is then a marked deceleration in an effort to meet the INTERMEZZO (5:22) which wanders in on oboe and harp with all the traditional sweetness and grace one expects from such a movement. Clever use of bell tones supplies a soft warning of impending tragedy before a repetition of the oboe/harp passage to close the piece . EPILOGUE (9 :35) makes massive use of an erratic march theme to draw out Expedition fatigue and drifts to quiet passages to depict utter exhaustion before sealing off the human element to the rest of the movement. All that is left to do now, is for the choir and wind machine to cover the brief tracks of this unfortunate polar venture . EMI then thoughtfully runs a silent 15 second groove for listener emotional adjustment before the click- clack of cam and spring exchange ice for carpet.

____________________

‘I do not regret this journey ; we took risks, we knew we took them, things have come out against us, therefore we have no cause for complaint.’

- Scott's Last Journal.

______________________

LIFE ON THE ICE: THE COLDEST PLACE ON EARTH

Robert Thomson

A. H. & A.W. Reed, 1969

At an Antarctic Society function in 1967 Bob Thomson told me the tale of his visit to the Russian base of Vostok, 12000 feet up on the polar plateau. He told me nothing of the extraordinary hardships that his team experienced in getting there - just an eerie story of this seasonally deserted scientific post which greeted the climax of their 900 mile traverse. Subsequently, I lay in wait for the promised publication of his book - something which evaded me until just recently when I noticed it on sale at half its original price. Reeds' were obviously clearing their shelves.

In these reviews, I steer clear of books on 'the ice', as the library is vast and the subject matter not aligned to our normal topics. An isolated write up might be done because a book contains a section on the sub-antartic islands. In this case however, it is because so many members know Bob well, and may have either forgotten or did not know that he eventually got to the printers six years after his 1962-3 adventure.

Bob went south with the 'Thala Dan' in December 1961 as leader of the ANARE team for Wilkes, one well known face amongst them belonged to Eric Clague, now of our Mangere met office.

Apart from the routine operation of the base, Bob was obligated to a 200 mile traverse (Totten Glacier) in the coming autumn - to lay down 30 drums of fuel for use by a summer team which would operate in the unknown southeast sector. It was an uncomfortable trip for the two D4s and Weasel, and perhaps a little worse for their occupants, but a lot was learnt and modifications to equipment were made over the winter period. A generous offer by the USAF out of McMurdo, of an airborne supply drop of fuel for the coming traverse, suddenly made Bob realise that Vostok was on the cards - an empty deserted camp well to the south. But what a tie up with the known Russian scientific findings in this region if a 900 mile profile of seismic shots and gravity plots could be established commencing at Wilkes.

The 120 days which followed, took the six man team through an icy hell of blizzard and temperatures ranging from a hot minus 10 to a life stopping minus 120 farenheit. Far from creating a rest period the ultimate goal of Vostok turned out to be a time and energy absorbing experience as the station's altitude and antiquated equipment did little to rebuild the traverse exhausted men.

That the programme was fully carried out is undoubtably a fine tribute to Bob's qualities of leadership and the extraordinary mental and physical effort put forward by his team members.

The story is generally well told - not brilliant - but lucid and with good continuity. Full text of the more important signals passed between the Russians, Americans and ANARE are included, and scientific terms are brought to the level of the armchair adventurer in an adequate manner. The illustrations are excellent and well prepared graphs are included for those with a mathematical bent. Also, a pleasing effort has been made in the general quality of the book by Dia-Nippon, the Hong Kong printers now carrying out most of Reeds' work, but Bob might have missed the cue with his title. The bookshop browser may well pass it by in regarding it as just another publication on Antartica, surely 'the coldest place on earth' (but who has not been stopped in their tracks by Adrian Hayter's title ‘Year of the Quiet Sun' and that exquisite cover photograph of his). For my money, however, all Bob's hard work is worth the original price. At the present sale ticket - its a snip.

Pierre.

********************

5th ANNUAL REUNION

A more spacious venue and larger orchestra has been chosen for this year's Reunion. We are off to the Seaway Cabaret on the Petone foreshore for the night's festivities from 9pm to lam. Make sure you set aside this date to meet your mates. Thrilling night panorama of Wellington Harbour thrown in at no extra cost.

Organisers: Ian Bailey & Robin Foubister.

SINGLE: $6 DOUBLE: $12

********************

Just Before Going to Press: (Dominion 22/8/172)

"ISLAND'S GOATS AND CATS FACE ROUGH TIME.

Wild goats and cats roaming in their thousands on Raoul Island are in for a rough time after the research boat, ‘Acheron’ , arrives there from Gisborne on Thursday morning. On board, in addition to a crew of five, are eight officers drawn from the Wildlife Division of the Department of Internal Affairs, New Zealand Forest Service, the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research and the Lands and Survey Department.

They have with them rifles, ammunition, traps and eight dogs. They intend an all-out blitz on wild goats and cats during a seven week's stay on Raoul Island. 'Goats and cats have been on the island for about 100 years and are playing havoc with vegetation and birdlife', Mr C.R. Veitch, of the Wildlife Division, Auckland, and co-leader of the party said yesterday. 'The goats have stopped the regeneration of the forest, and at least two species of plants cannot now be found'"

********************