A bearded Alan Averis rolls out the Fordson and trailer for the start

of the 1961 servicing at Raoul Island. (Publicity Studios)

CAMPBELL-RAOUL ISLANDS' ASSOCIATION (INC.)

NEWSLETTER Vol 2 Number 6 MARCH 1973

Association Officers 1972 - 73

Patron

Air Vice-Marshall A. H. Marsh C.B.E.

President

Tony Bromley

| Secretary | Treasurer | |

| Dave Leslie | John Caskey | |

| Committee | Honorary Members | |

| Bernie McGuire | M. Butterton | |

| Peter Shone | H. Carter | |

| Robin Foubister | Capt. J. F. Holm | |

| Ron Craig | I. Kerr | |

| Peter Ingram | C. Taylor | |

| Terry Smith | H. W. Hill |

Newletter Editor

Peter (Pierre) Ingram

"The Islander" is the official quarterly bulletin of the Campbell-Raoul Islands' Association (Inc.) and is registered at the Post Office Head quarters, WELLINGTON, for transmission through the Postal Services as a magazine. All enquiries should be addressed to: The Secretary, CRIA (Inc.), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON. Contributions to the bulletin should be forwarded to the Editor, CRIA (inc), G.P.O. Box 3557, WELLINGTON, and subscriptions to the Treasurer. Current membership rates are $3 per annum.

____________________

Editoral: RAOUL IN RETROSPECT

In the twilight years of our bachelorhood, when six o'clock closing provided the rosy glow of friendship and nocturnal reunion, a larger than normal group of fellows would assemble and noisely picket their chosen circle of linoleum from outsiders who would have drawn little interest from the conversation. These were the boys back from the islands. Some were young and free and talked of return by departmental means, but the others frequently cast their thoughts northwards and expanded on nautical themes, mentally anticipating the weather helm of ocean going cutters, which unfortunately would remain low on their financial priorities for at least another decade. They were the lads under the first pangs of the ten year itch- or the golden desire to return to the Kermadecs by one's industry. The paternal call came instead and they dispersed to carry out their duties. The reunions became monthly and in some cases dwindled to annual functions when the highlights of Their Year would flash within fading memories of a rare class of companionship and way of life. What would it be like to return to this temporary home at this later stage?

The itch was eight years old and showed no signs of abatement when I held my breath on a possibility of returning to Raoul with the National Film Unit in 1970. So distant the possibility seemed, that the stamp of reality was not impressed upon my mind until the basket swung clear and headed for the Rock. It was on. I knew most of the lads of '70/71 well and as soon as polite had shot up the track for a lone walk to the hostel. None of the magic of Raoul was missing as it seeped into my anxious appetite. The bush arched overhead in green silence and the earthy perfume of the bracken covering the north-west crater rim was heavy on the humid air. Down through Low Flat with a hopeful glance at the passionfruit vines, but too early for a feast. And then the same repeating clatter of the kitchen screen door, the dark coolness of the lounge with its crowded rogues' gallery looking down from the picture rail, the bar we rarely used as the kitchen was cosier. Nothing changed, everything in its place. The smell of the veranda's oiled floor and the frustrated buzz of the bush flies between screen and window. In the happy days that followed, I wandered through my old bush haunts, found that beautiful glade of minature ferns again and felt the healthy tug of the beach fish. The camp area was fastidiously being cared for and the banana palms had finally come right. By night the hostel warmed to the team's companionship and friendly noise which would slowly fade through tiredness until only the muffled thump of the over-night diesel could be heard. For nine days I felt a rare joy.

There is little doubt that the late Alf Bacon (Vol2, page 107), honorary Association member and oceanic hitch-hiker extraordinary has been the most determined member to return to 29 South. Thirty six years were to elapse before he made it back in 1927 for the inspection of the Low Flat freehold, and then a further eight before he thumbed down Johnny Wray and his cutter 'Ngataki' for the 674 mile journey. But Alf wasn't going for a holiday - he hoped to be going for ever, and to this end, packed his 14 foot dingy, two friends and two dogs into the yacht 's 35 foot confines. It is now well known historically, that the P .W.D. evicted Alf through shear departmental necessity in 1937, but I later read a letter of his written in Otaki and dated 1962, where he expressed the golden desire to once again visit Raoul's peaceful shores.

And the ten years has now elapsed since our little group debated the possibility of return. Perhaps, by Alf's lesson, we may feel the itch for some years to come.

_______________________

THE NAUGHTY FORTY: It is a little disappointing to note that as we go to press, some forty members are behind in payment of subs for the 1972/3 year. So lads, I've had to include another reminder slip with this issue to jog the memory- which you may joyfully ignore if you have posted in since early March.

__________________________

KNIGHTHOOD: Members will have been pleased to note the recognition of Dr Robert Alexander Falla's services in the recent New Year's Honours List. For the record within our own pages, I quote from 'The New Zealand Herald': Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire: Dr R.A. Falla who has given outstanding services to conservation.

He has been chairman of the Nature Conservation Council since it was formed in 1962. The work of the council has expanded considerably under Dr Falla's leadership. He has taken a leading role in the establishment of conservation week in New Zealand and in the launching of a network of conservation societies throughout New Zealand. From 1937 until 1947 he was director of the Canterbury Museum and from 1947 until 1966 director of the Dominion Museum. He has been a member of the Ross Sea Committee since 1955 and has written many scientific papers and reports. Dr Falla was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the Queen's Birthday Honours 1959 for outstanding services in scientific work and as director of the Dominion Museum.

A telegram to help mark the occasion was sent by the committee on behalf of the Association to Sir Robert and Lady Falla .

****************************************

THE QUARTER'S CONTRIBUTIONS

In the last issue we recorded the current expedition to the southern islands in the motor launch 'Acheron' and already we have a report by one member from the section that returned to New Zealand in December. Our thanks to Dr Charles Fleming, whom I erroneously promoted to the directorship of the NZ Geological Survey in Vol 2, page 76. Seems Dr David Kear is not ready to hand over the reins of office as yet, but it was a nice try by your editor. Charlie promises an article of his landing on the Snares Western Chain in the not too distant future, which we naturally look forward to receiving.

As a tribute to those who stood guard on the islands in the Southern Ocean during the war years of the 40s, I have reproduced a "revealing" article from the 'Auckland Star' dated Friday, November 23, 1945. Hot news then and still informative almost thirty years later, it was made available by Laurie Pollock (Vol 2, page 76) who was at Carnley 1941, Port Ross 1943 and leader Campbell 1944.

And from another war comes the first installment in a three part story of the German raider 'Wolf's' activities in the Kermadecs . The tale comes directly from Roy Alexander's book (Recommended Reading , Vol2, page 63) in two sections with a concluding article on technical details and notes by J.A. Henderson (surveyor, KIE, 1937). Then there is the concluding section to Ian Kerr ' s seventh historical chapter on Campbell Island , 'Depots for the Shipwrecked and Protection of Seals,' which we could not completely squeeze into our last bulletin. We wish you happy reading.

___________________

MEMBERS COMMENT

Another letter from Ed de Ste Croix out on the Chats: "We have now commenced our second year on the Chathams and last evening (18 Jan) CRIA members held another Chathams branch get together at our home. Guest of Honour was Gerry Clark of the yacht 'Ketiga', who regaled us with some of his lone yachting exploits and adventures. Present for the evening were Bill Stuart (C69), Larry Garnet (R69) Robb Stanley (C51 & 55) and myself (C61, 64 & R68), plus Bill's wife Renny and my wife.

Gerry initially sailed from Keri Keri, in the Bay of Islands, on a sponsored 2400 mile journey (50cents per mile) to raise finance to save the area of land around the Old Stone Store from commercial development. By the time he returns to Keri Keri he will have sailed well over 3000 miles in his 21 foot yacht 'Ketiga' which is a Malay word meaning 'the third.' After departing from Keri Keri the course was over the top end of New Zealand and down the West Coast of NZ (out of the sight of land) to Auckland Islands where Gerry met Brian Bell and his wildlife party. He was shown around part of the island and then sailed on to Campbell Island arriving on 23rd December, just in time for the Christmas and New Year celebrations. Gerry enjoyed his stay very much - no doubt the team showed all the usual grand hospitality which succeeding teams have bestowed on visiting bodies. Gerry arrived at Auckland Is, Campbell and Chatham Islands in the dark. As he said, "It is just as well, because when daylight revealed the topography of Perseverance Harbour, it gave me food for thought." A near brush with Shoal Point in the dark was something he prefers to forget - no doubt.

From Campbell, 'Ketiga's' bow was pointed in the direction of the Antipodes, but on arrival the islands were shrouded in fog, so onwards to Bounty Island which were clear, Gerry sailed close enough to view the penguins. The Chathams were reached Tuesday 16th January, where 'Ketiga' is anchored at this time. Gerry hopes to sail about Sunday 21st direct to Keri Keri. We wish him luck in his efforts to save a historic part of New Zealand from commercial development.

Regards

_______________________

And jottings from my Diary whilst northbound in 1970 in the Navy's Endeavour:

Tuesday 17th November:

Weather identical (with yesterday), low vis, small cumulus and extensive Sc at 5000 feet - sea shows light - mod swell, 20 knot NE by mid-day to dusk. Wanderers still with us this morning and throughout day, one Black Browed Molly joined us at midday and brief visits by Shearwaters. Ship slowed to 10 knots to make L'Esperance by 0900 tomorrow. Most of day spent looking at the sea, but not without some interest. Food at all meals is excellent, but still to find the lad that issues the bedding.

Wednesday 18th:

Situation appeared unchanged this morning - Sc persists at 5000', NE at 20 knots and vis at 10 nms. L'Esperance sighted 0830 and boats away 1000 - eight ashore landed OK and soon on top. Six bird types reported- grey ternlet (possibly 5000), wedge tailed shearwater - blackwinged petrel amongst them. (Wanderers left us this morning) Vegetation almost entirely ice plant, no Ngaio or any shrub life. Ship standing off 1/2 mile in moderate swell. Lava dike appears to East of island and beautiful lava bridge to West reflects pale pink in light reflected from foam. Boys aboard and underway by 1300. John brought back rock samples which I was very glad to accept. Volcanic crater is on NE face with surrounding 80' cliffs. Ternlets now resettled and all at peace. Full ahead at 1330 for Curtis and Cheeseman to be there by 1730. Have entered shower area, 50% coverage, vis generally 5 nm. Boats away with 6 shore party 1730, light shower. Cheeseman is only a rough eroded pinnacle, but Curtis better formed. Lynton speared a 55 lb kingy off island. Boats return as no suitable landing found and dusk coming on. Steaming downwind 10 knots on 260 degree magnetic will return on 080 at 0130 to lay off around 0900.

Thursday 19th:

Weather similar but cleared during day with vis increasing to 10 nm. Boys away and on shore Cheeseman by 1030 transferring Curtis by 1200 boats stowed l300 downwind until 1500 return and layoff 1630 all aboard by 1730. Steam downwind 1800, to turn around midnight and make for Macauley to lie off 0900 tomorrow. Boys brought back good sulphur rock samples, Curtis crater active with considerable steam venting and one good size grey mudpool - would have loved to have seen it . Hard time going ashore in the surge, Bill Sykes getting a good ducking and some frantic dog-paddling to regain the whaler, boots and all. They then had hard climb to the top of Curtis. Bill has examples of ice plant - specimen typical of what one sees in New Zealand with small fleshy leaf about 1 1/2 to 2" long and small pale purple flower with dozens long petals. Top of island is covered in sedge grass with small colony of boobies nesting - about a dozen. Great number of grey ternlets feeding at sea. Colours of these islands in exposed cliff faces almost identical to Campbell's north-west cliff faces. Lynton has caught 4 yellow fish (specie unknown) could be the discovery of the trip (later identified as member of the Drummer family-Ed) . Also a good kingy at 65 lb.

Friday 20th:

Wind backing to 340 degrees and freshening 25 knots, cold front to West , good Cb heads, easterly progress appears normal. Macauley ahead in haze standoff and boats away 0930. Boys make circum-navigation and find the sandy bay quite OK. First stores away and all back for lunch but for John and George, both visible at top of Mount Hazard by mid-day. Small herd of 7 goats located with head billy spoiling for a fight. Possibly more to windward side of island. Regrowth is strong, heavy mat of grass eases towards higher ground, spongy to walk on. Heavy clumps of tall grass - Hazard Island, virtually virgin shows heavy shrub cover . This island is amazingly high and steep. Cliffs of Macauley appear sedimentary in sunlight but will be similar to Raoul only far lighter in colour. This pumice cover is 3-400 'deep in places with dark lava showing clearly below. Island's general contour from the south is rather lion-like facing west. Jchn brought back some good rocks for me All stores including water (4 x 44 gals) and personnel are a shore now . Steaming approx 240 degrees, returning tonight to lay off Raoul by 0930 Saturday.

Pierre

***********************************

A Grey Headed Mollymawk of the Bull Rock colony poses for

Dr M F Soper's camera during the Wildlife's 1970 expedition to

Campbell Island.

***********************************

AUCKLAND ISLANDS REVISITED

C. A . Fleming

On September 26, 1942, during a year of wartime coastwatching at the Auckland Islands, I spent a long day, never to be forgotten, on Enderby Island, off Port Ross, and ended up with a wet arse after the dinghy was twice swamped in the southerly surf that had developed while we were ashore for the ‘Ranui'. On that day I briefly observed an exposure of varve silts , interbedded with the moraine that caps the island. Certain details of this exposure had puzzled me for 30 years and were one of several geological problems that gave substance to a nostalgic desire to go back. The opportunity came with an empty berth on the R. V. 'Acheron' ( Mr A.J. Black) which transported the stores and members of the first party of the Lands and Survey Auckland Island Expedition 1972-73.

We assembled in Dunedin on November 27, but loading occupied all next day and we did not sail till the evening of Tuesday, 28th, after signing as crew. The ship had just returned from a stormy trip to Antipodes Island and I anticipated a rough passage south, remembering the week or more spent wallowing and tossing in the 'Tagua', an auxilliary ketch, in 1942-43. The ship's party included (besides Mr Black) his son Sandy, Ian Macdonald, Dr A.R. Baker (National Museum of New Zealand Zoologist, serving as crew), Brian D. Bell (Wildlife Service) in charge of the shore parties , Mr and Mrs Basil Marlowe (Australian Museum and Sydney University), Gerry Van Tets (C.S.I.R.O. Canberra), Lester Petersen (U.S.A.), Mike Rudge and John Campbell (Ecology Division, DSIR), Rodney Russ (Wildlife Service), and Mike Soper (Medical Officer and photographer).

Weather and forecast were so good that a course to the Aucklands was taken from the Nuggets thus saving about five hours. The dead reckoning distance between the shelf edge SE of the Snares and N of the Aucklands (plotted by echo-sounder) gave a check on drift and position on Thursday morning and after the land was seen at 1030 flights of Auckland Island Shags escorted the ship into Port Ross.

At Ranui Cove, site of the No. 1 Coast watching Station, the boulder jetties were still useable, tracks could still be followed and the house (restored by a Dominion Museum party in the sixties) was weatherproof, though sea lions had broken some duck-walks. A wood pile of neat rata stove-lengths dated back to World War II and so did pin-ups and ship identification charts in the lookout, which I reached by following the telephone line (8-gauge) strung with insulators that had mainly pulled out of the rata trunks. Dracophyllum corduroy work and steps had lasted well on the track. Port Ross was suffering a drought so that cushion plants and bog had dried out and cracked. There was a fire risk. Tits and bellbirds were feeding young. The panoramic 360 degree view from the lockout roof is immortal, unchanging and the sun broke through high clouds onto the rata wind-rows forming a foreground to Mt Eden, Meg's Hill, Dundas, Kekeno and Deas Head, with Cavern Peak and Giant's Tomb standing up clearly in the distance. Allan Eden's base-line marker looked as if the cement had set last week. I walked towards Cape Crozier, photographing a sea-bear with yearling pup, an aggressive immature sea-lion and a peaceful skua, but did not get to the Sooty Albatross ledges. Near a fallen rata not far from camp was a seedling Olearia, the first, I think, in this area. Cats had got a few prions along the coast and pig rootings were everywhere in the dry forest litter.

Next morning while the Enderby Island camp was set up at the SW end of Sandy Bay, Lester Petersen accompanied me across the island, past Royal Albatross nests to the NW coast to seek my varves. Bulbinella was in glorious full flower and I had forgotten how colourful the local gentian can be.

First I reconnoitered westward, viewing part of the cattle herd, then eastward, locating the exposure about noon while Lester photographed Sooties, and spent an hour observing and photographing the fossil gullies and moulin pot-holes penetrating the varves before continuing NE to Derry Castle Reef. We were due back at 3 pm so could not complete a circuit and made back overland, with photographs of shag, Sooty Albatross, Yellow-eyed Penguin and Antarctic Tern nests and a Blue Rabbit as a bonus, scrambling rather uncomfortably through neck high Cassinia scrub.

The next visit was Erebus Cove, site of the old Enderby settlement of Hardwicke and of the castaway depot and graveyard, where Rudge and Camrbell's camp and stores were landed for research planned on goats. Then we picked up Alan Baker, who had been preparing a seal skeleton at Ranui Cove for the U. S. National Museum, and made out to sea in the long subantarctic evening with a lazy swell, the six of us staring the night watches. The afterglow 1n the SW lasted till 10 and after that Orion's Belt slowly rose and fell to the starboard in a miraculous clear sky. The fine weather lasted till we got to Dunedin on Sunday afternoon (Dec 3), having spent the previous day at the Snares and its Western Chain - but that is another story.

**************************************

“CAPE EXPEDITION” STOOD GUARD IN SOUTHERN WATERS

- Auckland Star, November 23, 1945.

On the eve of war, in August, 1939, the German steamer 'Erlangen' left Dunedin, heading, ostensibly, for New South Wales. Australia never saw her, however, and many months later she was reported to have reached a neutral port. The vessel did not carry sufficient fuel when she left Dunedin to reach that port.

Towards the end of 1940, German raiders were operating successfully in New Zealand waters. Prisoners taken by the raiders reported that after being captured they sailed far to the south, where they caught glimpses of a tussock-covered island. In April, 1941, the trading schooner 'Tagua' slipped unostentatinsly out of Wellington. Her crew appeared to be civilians, but revolvers, rifles and tommy-guns were included in the remarkably wide range of equipment stored below decks . About the same time the graceful ketch 'Ranui' disappeared quietly from Stewart Island waters and did not return.

These facts appear to be unrelated, but to a very small circle of New Zealanders they were all connected with what was one of the Dominion's best-kept secrets of the war- the Cape Expedition. Today applications are being invited from meteorological personnel for service on Campbell Island, a bleak, tussock-covered piece of land only 30 miles in diameter, lying about 400 miles south of Bluff. This is the peacetime application of the Cape Expedition, which was a coastwatching venture carried out by New Zealanders on the Auckland and Campbell Islands.

Dominion intelligence officers were quick to realise the potential uses of these uninhabited islands to the south. The Auckland Islands, some 290 miles south of Bluff, possess several good harbours, Port Ross, in pcrticular, being described as one of the most sheltered anchorages in the world. In addition, there was rata wood for fuel, and wild cattle and the provisions of a shipwreck relief depot for food. Campbell Island also offered good anchorages, and nearly 2000 sheep grazed on its steep slopes. Here also was food and shelter for vessels operating far from their homeland. The 'Erlangen' incident told its own story. When the raiders began operations the point became obvious. The War Cabinet acted, and the Cape Expedition - the name was chosen deliberately for its vagueness -was authorised.

The 'Tagua' left Wellington manned by volunteer naval ratings and carrying engineers from the aerodrome services branch of the Public Works Department. They were the advance party. A call for volunteers went out to the armed forces. Applicants were rigorously examined. The task called for more than bravery. The men had to be self-reliant and of a temperament which would stand up to a year without contact with civilisation. Keen biologists, geologists or meteorologists were obvious choices. Until they had left port the coastwatchers had no idea of their destination. They had been told that their job would be a lonely one and might involve capture by the enemy, but that was about all. As far as their relatives were concerned, the men simply disappeared. The only news received by next-of-kin was a monthly official notification reporting the man concerned to be safe and well.

Rations were made up carefully. They had to last for 12 months and they had to be of a nature to keep men healthy under sub-Arctic conditions. Fresh meat, fortunately, was there for the shooting. Two watching stations were established on the Auckland Islands, one at Carnley Harbour and the other at Port Ross, while the 'Ranui' maintained a continuous patrol of the inlets of the group. On an average there were ten men ashore on the Aucklands, four aboard the 'Ranui' and five at the Campbell Island station. They were an inconspicuous band . Living quarters and radio stations were camouflaged, and care was taken to avoid making tell-tale tracks in case of an aerial reconnaissance of the supposedly uninhabited islands.

Each day a radio report was sent to Wellington. The schedule for the signal was staggered, and, apart from this one flash daily, complete radio silence was observed. Duty watches evenly covered the hours of daylight. In the summer, early dawns and long twilights meant that watches had to be kept from 3 am until 11 pm. Earlier suspicions of enemy interest in the islands were confirmed by the 'Ranui'. In Carnley Harbour a large area of rata had been felled for fuel. Nearby was found a German hammer.

The coastwatchers, generally speaking, enjoyed the experience. That, at least, is the impression of two members of the expedition, Messrs. L. Pollock and Graham Turbett, who are at present attached to the R.N.Z.A.F. in Auckland. The men had little spare time. When they were not on watch - a duty carried out usually in several sets of clothing to combat the wind and the cold - there were plenty of chores to be attended to. Mr. Pollock, who was the leader of his parties during three twelve-month spells on the islands, organised, among other distractions, Saturday night "dances." On such occasions the five men of the party solemnly practised the latest dance steps to the strains of their radio receiving set, for which reception was remarkably good. A sports meeting was another highlight. Events took a whole day to run off, and ranged from archery to tiddly-winks. Trophies were manufactured from local materials, and each competitor proudly carried off a cup.

Towards the end, as the likelihood of enemy shipping in the area lessened, the expedition became almost entirely scientific in character. Radio silence was broken to allow meteorologists to flash weather reports from the area. The Department of Scientific and Industrial Research became interested in experiments made with ionosphere equipment. Geologists and botanists, for whom the islands were a scientific paradise, pursued their investigations with enthusiasm.

The scientific investigation side of their activities is regarded by those who should know as being of the utmost importance. And even though an enemy ship was never sighted the contribution of those lonely men to the war effort of the Dominion cannot be under - rated. They were set a task which would have appalled the average man, and they carried it out cheerfully and conscientiously. It was unspectacular work, but it should not be overlooked by those they were protecting.

**********************************

Part One: The WAIRUNA's Interrupted Voyage

by Roy Alexander.

The cargo steamer 'Wairuna' was pushing along past the Kermadec Islands, in the South Pacific. It was June 2nd, 1917, and the war had been in progress for nearly three years. But war, and all that, seemed very far away to the group of ship's officers having dinner in the 'Wairuna's' stuffy little saloon. The meal was not a success; there was decided stiffness, a strained atmosphere. Our captain had taken command of the ship after long service as a chief officer of smart mail steamers, and obviously he disliked the freighter system of serving a hot dinner at mid-day. Besides which the captain's expression showed that he had noticed that the steward's white coat was soiled and the man had slopped the soup.

Other matters contributed to the uncongenial feeling; few aboard knew each other well, the ship was only two days at sea and it was a new crew. There had been no time to make friends and know each other's ways . Then there was another irritating detail. During the morning the ship had passed Macauley Island and a few small outlying islands of the group; after passing these the cliffs of Sunday Island loomed up ahead. Sunday Island is the largest and most easterly of the completely uninhabited Kermadecs. The high northern cliffs had become clearer before dinner, and the masts of a steamer were seen rising above the rocks at the north-eastern point of the island. From the size and position of those masts it appeared that a large steamer was anchored off the other side of this point.

Rees, the 'Wairuna's' second officer, was Welsh, fiery, and inclined to be dogmatic. "A raider, sir," he remarked to the captain after turning his glasses on the stranger's masts. "She's certainly a raider. Shall we shear off, sir ?"

Now masters of ships are beings apart while aboard their vessels and direct recommendations must not be made to them. One must only imply, make only the lightest and most indirect suggestions, when addressing a master mariner on his bridge. Captain Saunders bristled slightly at Ree's remarks, then registered mild amusement. "A raider? Ridiculous, Mr Rees. She's probably a Burns Philip steamer loading copra." So the 'Wairuna' was holding her course, which would eventually take her close to the anchored stranger. Big events were to hinge on this slight snappiness in the air at the beginning of the watch.

As the ship settled down to the usual quiet routine of an afternoon at sea aboard a cargo steamer, I sat down at the table in the wireless room and did the regulation half-hour watch. Aboard ships carrying only one operator it is customary for the time on duty to be split up into a number of short watches. The wireless installation aboard the 'Wairuna’ had been hurriedly fitted in a cabin off the dining-saloon just before the ship left New Zealand on her trans-Pacific voyage; it included a carborundum receiving set which was efficient for moderate distances. Nothing was doing on the air; with crystal receivers the difference between daylight and night reception was very marked. Although the big shore station at Awanui (near the North Cape of New Zealand) was only about four hundred miles in a direct line from the ship, the 'Wairuna' would not be in touch with that station till nightfall. So there was no way of knowing what ships were in the vicinity. War regulations did not permit the transmission of CQ calls, unless in an emergency.

The early afternoon watch was over; I had dropped the earphones and was lying on the bunk in the wireless room cabin when the steward whose soiled white coat had annoyed the captain at dinner walked in. He was not wearing the offending garment when he brought in the tea; in fact he wore only a singlet and a pair of trousers much dirtier than the coat and he was in a mood for a little bright gossip. He mentioned that an officer had cut his throat on the bunk on which I was then lying, and that the cabin had not been used since that occurrence till it was found to be the only suitable place on the ship where a wireless set could be fitted. He also told some gruesome details of a seaman who had been decapitated when a spring parted on the fo'c'sle head; dropped some scandalous hints concerning the private life of somebody on board, and then rattled on that we were now passing very close to Sunday Island. He said that I should really get up and have a glance at the fine looking ship lying off the island - but the steward's chatter was interrupted at this point.

A roar which could come only from a plane engine suddenly drowned the steady thumping of the ship's engines. An explosion sounded somewhere near the ship. The tea things went flying as I, the steward by a head along the short alleyway to the deck; to find the engine room staff getting up on deck and the watch below running aft from the fo'c'sle as a seaplane circled down over the ship. The plane was flying so low that it appeared to be just skimming the ship's masts as it flew over the ship. It was a two-seater biplane with the lower wings painted with black German crosses, and the observer could be clearly seen dangling a long, pearshaped bomb over the side.

"Don't touch your transmitting key," said Captain Saunders when I ran up to the bridge. "Wait here for a moment." A seaman came running to the bridge with a message attached to a sandbag which the plane's observer had dropped on the fore deck. "Do not use your wireless. Stop your engines. Take orders from the cruiser or you will be bombed," was the message written in English. The seaplane dived again and planted a bomb just ahead of the ship to emphasize the order. The 'Wairuna’ was in a hopeless position. She had steamed past the cliffs of the island and her course had taken her right up to the strange ship now within a mile of us. Several of her guns were trained on our ship and a boarding party was already on its way. Second officer Rees, in a corner of the bridge with his arms folded, was positively exuding I told you so righteousness.

"Get rid of your log-book, and don't touch that wireless key," were Captain Saunder's final instructions. Down on deck outside the saloon about half the crew were milling round what appeared to be a sizeable lucky-dip; the chief steward had dragged out the ship's supply of tobacco and tins of cigarettes. Below in the stokehold an officer was pushing some ship's papers and codebooks into a furnace, the wireless log and codes followed. Back on deck the steward was outside the wireless room struggling into that white coat of his. He seemed to think it a sort of uniform that would make his status clear to the Germans.

The wireless set was new and was too useful to leave intact for the boarding party, so the receiver was levered from the table with a spanner and dumped overboard. Most of the transmitting gear followed the receiver. I was rooting among other odds and ends to see that nothing important had been overlooked when a German officer appeared in the cabin. He was swinging a revolver and had two seamen with him, but was quite pleasant and polite.

"Good afternoon" he said. "Your papers, please." He was not over pleased at finding everything of importance gone, but we were taken in to the saloon and questioned - all without fuss. The chief steward even served tea while we were in the saloon, the German officer politely taking a cup with us. A big party of armed men had come aboard with two German officers. Immediately they came over the side they made for pre-arranged points, the bridge, the engine-room, etc - and had methodically taken full charge.

After the tea-drinking (tea and pirates seemed a queer combination) those of us who had been under guard in the saloon found ourselves being ordered over the side into the cruiser's launch, still with much politeness. All the navigating officers and the chief engineer were aboard the launch; others of the crew were detained aboard the 'Wairuna' for the time being. It was after sunset by this time, but we had a good view of the cruiser from the launch as we came closer; and a solid, efficient-looking vessel she was. There was now nothing to distinguish her from an ordinary merchantman, her hull and funnel were painted black with touches of dark grey about the upper works. Most British merchant vessels were then painted war-grey, and this ship was a little darker than the usual colour; but there was not enough difference to make her noticeable. Her guns had been swung inboard and were not now visible. She appeared to be of about 7000 tons, a long open bridge-deck giving her an appearance similar to the then well known Kashmir class of P & O Liner.

The resemblance to a liner ceased abruptly as we went up a rope ladder and climbed over the side between a torpedo-tube and a 5.9 inch gun to the after deck. The ship was swarming with men (there was a crew of about four hundred, we found out later) and on the after deck alone, the only part of the deck we then saw, there were two torpedo tubes and two big guns. These were so well hidden behind hinged steel sides that this armament could not be seen even at close quarters when aboard the launch. Taken from the after deck to the space under the raised poop, we were stripped and searched, and all letters and every scrap of paper were taken away to be examined. We had then to soap ourselves thoroughly with some sort of antiseptic soap, after which we were given our clothes and taken down through a small hatchway to the prisoners' quarters, in number four hold, right at the stern of the ship. Down the ladder we found ourselves in the ‘tween decks, a filthy, square, steel box covered with coal dust and with a mob of about a hundred men around us wanting news of the outside world. The prisoners were of all types of seamen - white, black, brown and brindled. Most were almost naked in the clammy heat, but some were still wearing shabby and ragged mercantile marine uniforms. The story these men told was even stranger than their appearance and surroundings. All had been captured and their ships sunk in the Indian Ocean months ago. Some had been prisoners aboard the ship for over three months.

The raider we were aboard was the 'Wolf', a warship unknown to the allied naval authorities. For that matter she was unknown in Germany excepting to a very few officials. Even these did not know that she was still afloat after six months at sea. A combination minelayer and raider, she had already sown mines off Capetown, Colombo and Bombay, and half of her cargo of mines still remained aboard. The prison hold in which we were standing had originally been one of the mine compartments, and had held the mines that had sunk the 'Perseus' and 'Worcestershire' off Colombo some time earlier and the mine the liner 'Mongolia' was to strike off Bombay in a few weeks from this night. The first of the prisoners had come aboard soon after this particular hold had been emptied of mines. Our new friends rushed us over to the bulkhead separating us from number three hold that held the remaining mines. Through a few rivet holes in the steel bulkhead we could see the mines - two hundred of them. Standing lashed down in long rows , each resting in its own steel sinker, they looked exactly like rows of black, barrel sized eggs standing in egg-cups. It was impossible to keep back the the quick thought that flashed through our brains as to our fate if one shell from a stray cruiser was to drop among that cargo. Two hundred mines - and only a few feet away. 'We quickly turned the conversation to other topics.

Captain Meadows appeared to be the leader among the prisoners. He had been master of the 'Turritella'; the first vessel captured by the raider. A massive, determined looking New Zealander, Meadows was quite the right man to lead that mixed collection of men. There were English, Irish, Scots, Portuguese, French, Italians and Mauritius halfcastes. There was even an Arab fireman from Port Said and a Levantine Jew. This was only the beginning of the human hotch-potch we were when the 'Wolf' arrived back at Kiel nine months later. Then, about thirty different races and nationalities were represented in the prisoners who swarmed from her holds. Captain Meadows said that the ship's band had been playing on deck when the 'Wairuna’ had poked her nose around the cliffs and that the bandsmen had dropped their instruments and run to action stations, leaving only the big drummer, who - either deaf or lost in his art - had kept banging away at the drum on his own.

Captain Saunders said, "You have been aboard here for three months. and when do you think we shall be released?" "We have no hope of being released," replied Meadows. He prophesied correctly, as events occurred. "You see, the whole success of the 'Wolf' depends on no information leaking out regarding her. We shall return to Germany with her - if she ever gets there." "Good God,” wailed Captain Saunders. "Not for months?" It was typical of the planning that had gone into fitting out the 'Wolf' that even such a detail as placing hammock rails in the mine compartments to accommodate possible prisoners had not been overlooked. We turned in. And so began our first night on the raider. Although the subject was not mentioned, the presence of those rows of mines, so close to us, was not conducive to the most pleasant of meditations before we dropped off to sleep. (to be continued ………)

**************************************

|

|

|

| Johnny wray and shipboard cat 'Rasmic' off the kermadecs during the KIE survey. | Wray's cutter 'Ngataki' at Auckland before leaving for Raoul. |

Photos: Alf Bacon Album

**************************************

Conclustion of CHAPTER 7

DEPOTS FOR THE SHIPWRECKED AND THE PROTECTION OF SEALS

by Ian Kerr.

(The larger section of this Chapter appears on page 115 of Vol 2.)

In the same year (1895), the Government desirous of patrolling the islands more frequently but unable to increase the number of visits by its own steamer, approached the Royal Navy. The Rear Admiral, Australian Station, was asked if he could send a ship down in June and December each year, while the 'Hinemoa' continued her visits in March and September. The reply was that no definite commitment could be undertaken, but that instructions were being issued that should prove satisfactory. In fact, H.M. ships shared inspection duties with the 'Hinemoa' and 'Tutanekai' during the next eight or nine years.

It has been mentioned that Borchgrevink, who accompanied Bull on the 1894 Antarctic expedition returned in 1899, this time in command of Sir George Newne's expedition in the barque-rigged auxiliary steamer 'Southern Cross'. When Borchgrevink's wintering party had been landed at Cape Adare, the 'Southern Cross' left for the north on 1 March 1899. It had been arranged that she would be met at Campbell Island by the brigantine 'Carin' with coal and stores. The 'Carin' arrived at the island on 1 February and waited there until 21 March when, as arranged, she sailed for New Zealand. The seven weeks spent at Campbell Island were described as monotonous in the extreme. Captain Jensen of the 'Southern Cross' sailed again for Campbell Island the intention being to recover some of the expense of the expedition by whaling and probably also to save harbour dues. Except for an abortive attempt to force the pack ice in early spring, she remained at the island for six months. A number of birds were collected by Captain Jensen and described in the expedition's scientific report.

A few weeks after the 'Southern Cross' arrived at Campbell Island, late in April, the Hobart barque ‘Helen' put in an appearance. The ‘Helen’, built in 1864 for the China trade, had been converted to a four-boat whaling ship in 1894. She is famous as the last of a long line of Hobart whalers and this was her last whaling voyage. It was probably not her first visit to Campbell Island; she had been whaling in those waters in 1898 and probably also in 1894. When the barque reached Campbell Island in May 1899 after a very rough trip, she found that the 'Southern Cross' had plenty of whaling gear but no facilities for trying out. The two captains therefore arranged that the ‘Southern Cross' would hunt and bring in whales and the ‘Helen's' crew would try out, each taking half the oil. This did not suit the 'Helen's' crew and there was apparently some friction, for after three whales had been caught, the 'Southern Cross' sailed away, probably on her sortie into the pack-ice.

While the 'Southern Cross' was away, the 'Helen's' crew decided to use shore-whaling methods. Whales had been seen to be plentiful near the west coast but it was not safe for the barque to attempt to operate here. Accordingly, the men dragged two whale-boats four miles from Perseverance Harbour to North West Bay. This took them four days in bitterly cold weather with snow on the ground. Their only shelter was a foresail, and several men were frostbitten. In spite of great difficulties they actually launched the boats and caught a number of whales, but the rough weather prevented their bringing in whole carcases. Some spermacetti was, however, obtained from the heads.

The two ships were together again in Perseverance Harbour in September 1899 when the 'Hinemoa' called. While the 'Hinemoa' was there an exceptionally fierce gale was experienced. The 'Helen' with 90 fathoms of chain to a 16 cwt anchor and 45 fathoms of 2 3/4 inch cable to a 24 cwt anchor dragged some distance. Some time after this the 'Helen' left for more northern grounds and returned to Hobart in February 1900 with 57 tons of oil. The 'Southern Cross' returned to Bluff for stores on 11 November and sailed for Cape Adare on 18 December 1899.

During the period from 1882 to 1906 the depots were gradually improved: boats were added, and permanent buildings were erected about l887; finger-posts indicating the whereabouts of the depots were erected about several places on each island; and, in 1906, the depots were re-built. From time to time, cattle, sheep and goats were landed and seeds of exotic plants sown. These were supplied, in the main, from the Invercargill Wreck Fund.

In 1910 it was decided that the Southern Islands cruises would in future, be carried out by the training ship 'Amokura' and this practice was followed until 1917. Some of the voyages into these stormy latitudes must have tested very thoroughly the seamanship and stamina of the cadets. The 'Tutenakai' later took up the running until late in the twenties when it was decided that the depots need no longer be maintained in view of the rapidly increasing number of ships carrying radio equipment. The last visit to Campbell Island was in the Autumn of 1927 but several more trips were made to Auckland Islands.

After 1883 the Campbell Island depot was not again legitimately used, but in 1895 it was found that stores had been stolen and the empty cases placed behind others in an attempt to conceal the theft. Although visits to Campbell Island continued until 1927, the depot was actually closed in 1923. The stores were removed and two sheds and a dinghy were sold to the Campbell Island Syndicate. Hope that a controlled, permanent sealing industry could be established was not abandoned for many years. The Marine Department's Annual Report of 1887 stated that there was "no positive information on whether any increase in the number of fur seals has taken place during the close season," and rather optimistically added, " but little doubt they have increased." In 1894, Mr J. P. Joyce, M. P., visited the islands in the 'Hinemoa' and prepared a report for the House. "On Auckland, Campbell and other Islands and on their Seals and Seal Rookeries." He dealt with animal life , geology and vegetation and even discussed the suitability of the islands for settlement. He also touched again on the suspicion that Macquarie Island traders were poaching seals at Campbell and Auckland Islands.

Perhaps, because fur seals were not increasing as expected while sea lions were relatively plentiful, Captain Bollons of the 'Hinemoa' was instructed in 1899 to bring back one or two carcasses of the latter beast. The subsequent report on the commercial value of the sea lion was to the effect that the skins were worth five to seven shillings each and that the oil was worth about one shilling a gallon but there was no demand for it.

There was another open season in 1913 and 490 skins valued at £529 were exported, but the total number taken and where they were obtained is not known. An Act of 1894 empowered the Department to draw up regualtions for the licensing of the trade and, in 1913, tenders for licences were invited. The annual report of the Marine Department in 1914 stated that the seals had not increased as expected since 1894, the failure again being put down to poaching. This result of over thirty years of patient efforts to build a profitable industry was so disheartening that the attempt was now virtually abandoned, although regulations controlling the industry remained in force and licences were issued from time to time.

While the Southern Islands have not the romantic appeal of tropical isles the 'Stella', 'Hinemoa' and 'Tutanekai' carried a great many passengers on their southern cruises; some seeking knowledge and others responding to the call of adventure. The majority were scientists but there were also photographer, journalists, sheep farmers, Governors and plain sightseers, including women. Among the journalists were Carrick, Lukins of Nelson and Fraser. A Southland photographer, Dougall, published in 1888, a series of twenty views of the islands and wrote a descriptive pamphlet to accompany them. His Excellency, Lord Glasgow, visited the islands in February 1895 and, in spite of weather which Captain Fairchild reported to be the worst he had experienced, was favourably impressed by Campbell Island. "Altogether, were it not for the severity of the climate Campbell Island is a most attractive spot and would be a very delightful possession. The land seemed if anything, better than at Auckland Islands." So ran his account in his diary, while his official despatch to the Secretary of State for the Colonies mentions the suitability of the islands for occupation. The next Governor, the Earl of Ranfurly, twice visited Campbell Island, in January 1901 and again in January 1902. His purpose was to collect bird specimens for the Briiish Museum. On his return from one of these trips he suggested that Norwegian Spruce and Larch trees might grow on Campbell Island. Lord Plunket also made the southern tour and his description of Campbell Island, like Lord Glasgow's, dwelt principally on the weather. "They (the shepherds) … told me that, though it was not nearly as cold in winter as the Shetland Islands (whence they came), it was a worse climate all the year round; and I gathered from their account that the weather consists of - frost, rain, then fog, then both together and then a gale of wind. They also mentioned casually that it made things worse when icebergs drifted into the harbour." In discussing the birdlife of Campbell Island, Lord Plunket mentioned the theory that, "The disinclination and inability to fly among these land birds is said to be the result of the survival of the unfittest, the more energetic having been (by degrees) blown out to sea in the course of their flight, and only the lazy flutterers left."

In this middle period of Campbell Island's history the scientific exploration of the island begun by Ross and Hooker and Filhol was continued by New Zealanders as were attempts at commercial exploitation. The 1atter came to an end with the cessation of regular communication with New Zealand. In the next chapter a brief account of the scientific work of the period will be given and in Chapter 9 the story of commercial enterprise will be concluded with an account of the sheep station and of shore-whaling stations.

*******************************

CAMPBELL-RAOUL ISLAND ASSOCIATION CAR RALLY

Saturday 17th March

The Rally:

Wellington members will have been notified by telephone by the time the Bulletin reaches you, but any out of town chaps that can make it, be in the Kelburn Head 0ffice (Met Service) car park at 2 pm. The rally route covers 62 miles of good roads around Wellington, terminating at Bernie Maguire's Paraparaumu home approximately two and a half hours later. Treasure hunt items are involved and each car must carry a navigator (and passengers if desired) as well as the ever necessary driver who should furnish a good map of Wellington to improve his times.

Tne Barbeque:

Will be at journey's end with a small prize-giving ceremony. Bring along your own choice of cow to toast over the charcoal and something to wash the dust down. Keep Saturday 17th March free for this gala occasion. If you can’t make it to the rally, make it to Bernie's by 5pm. Any inquiries - phone Pete Ingram after work at 783352, Wellington.

*******************************

NEWS FROM THE ISLANDS Compiled by Les Collins.

RAOUL ISLAND:

None of us had a very entertaining time during servicing and none of us realised the human body could take so much punishment and yet come back for more both physically and from an entertainment point of view. Most Islanders would appreciate that new expedition members are not anywhere near as fit as the outgoing party believe me it shows. Well, four days later everything was shipshape, well would you believe nearly semi-organised. Apart from tipping an unsuspecting farm inspector from the basket into the 'Holmburn' lifeboat little equipment was lost or damaged during this period. One Met observer is still lamenting the breaking of a bottle of black label scotch.

Three excellent full months have now been spent in this paradise. The following may give the reader some idea of life in Balihi. Cur new two works programmes are the building of an extension to the Met office and filling of Bell's Ravine together with the building of a concrete watercourse and apron. The building has progressed exceptionally well, internal linings and painting is all that needs to be done at this time. The ravine is a different proposition altogether; the amount of solid filling is astronomical. Does it help when a sudden downpour erodes a little more away? Not to worry - we will complete it.

To date 63 goats shot, not a bad effort considering the Wildlife boys had a field day here. One old billy was the largest goat I have personally ever seen.

Bought a bull calf up with us, a real character, but he is getting some what large now to fool around with. He fell off a cliff at Bell's Flat, an approximate drop of 10 feet. It took Andy (our farmer), Gavin (our Chef) and Lloyd (our Tech) all their combined efforts to haul him back up. Thank goodness this was early after our arrival and after kicking Gavin and Lloyd to show his appreciation of being rescued he was given a serious talking to. He now behaves himself. On the subject of farming (or more the farm manager), what would the reader do if the Chef said "separate the eggs please." What the farmer did was just as he was asked as he was assisting with Christmas decorations. He put white eggs on one side and brown eggs on the other.

Keith, the 2ic and Senior Met, and a few other titles at times, no longer believes in Father Christmas as he did not receive his new toy, a radar set. Gavin will believe in the old gentleman when he gets a new stove. We, the DSIR and the Dominion Museum are fortunate in having on the Island, John, the Maintenance Officer , as he is a rare professional bird watcher from the United Kingdom. The rest of us other than Collin the mechanic (another 'Englander' as we affectionately call them), are the usual Kiwi type bird watchers. Tell me, are hot pants still the fashion for Kiwi birds. John, however, is doing a first class job together with Collin's help for the scientific people and I trust that they will be recognised for it. Bruce, a Met observer, has done his thing for nature by not killing (as Bwana Bob does most readily) but kept it alive, single handed a ferocious beast, a kid goat standing all of 25 cm high. Amazing how heavy he got carrying him back from Prospect. Did not seem to worry Bruce, must be his military training, but sure did Bwana - something to do with the previous night.

The little fellow had to have a name, so it was thought fitting to honour our great white leader back in the concrete jungle, so we had our own "Leslie." Before any of the "wildmen" panic should they be reading this, "Leslie" met with a sad fate just as someone's car did late in 1972, so there he was found hung - self inflicted, so there was no need for an enquiry. A few kind words were said at his final resting place.

The keenness to work is amazing, especially in the Met Service. Tony (christened as "Woolly") arrives at the Met hut bounds into his work much to the amusement of the two other Met bods. An hour or so later someone realises it is his day off.

Our Tech is having a case of wobbly knees below the ankle - something to do with climbing a radio mast. It appears we all go deaf when he mentions it. The point is that the bribe is not high enough yet. Cooking has had its moments when not under the chef's control. It irks when one makes soup, especially red soup, like tomato and two characters tip it over their meat thinking that it is gravy.

We have had two trips out in 'Patsy' some doing a spot of fishing, others on to Meyer Island. Our sincere thanks to the 1971/2 boys for really making a grand job of the old girl. A pity they did not get the opportunity to have the pleasure we have experienced . On our first abortive trip we had a lark when after starting the motor we discovered a mechanic, unnamed, forgot to put the shear pin back after checking the motor. Sportswise, Collin is in front with a 60 lb bass for fishing, Bwana with 32 goats. For trying the hardest: fishing - Gavin, shooting - Woolly.

The only visitors we have had was the welcome RNZAF with an airdrop of Christmas mail and two days later the USCGC 'Burton Island' who dispatched two choppers to the island with bulk mail and taking off our outward mail, bales of wool and equipment. Several cases of oranges sent, met with a tragic fate due to the Christmas holidays, as they did not arrive at their destination for over three weeks. Still what is wrong with orange juice?

I understand that since 1945 we are the youngest team to leave New Zealand for Raoul with an average age of 24.2.

Bob (Bwana) Ferguson.

CAMPBELL ISLAND:

Following the customary delay, the 'Holmburn' departed Wellington to wallow its way southwards on 6 October 1972. The trip itself must have been a record for that ship, taking only 2 1/2 days to reach the island. Our second claim is that never did a wave break over the bow, not even for the photographers.

The servicing was completed with extreme efficiency with the aid of tte trailers constructed during the previous year. The elements were on our side with exceptional weather. Our party finally reached full strength with the addition of Bill Clark and George Money standing in for Brian Plummer who returned to New Zealand to have his appendix removed. The summer Met team, Mark Crompton and John Wilkinson completed the line-up. Having sorted out the stores, work began and we became adjusted to the vagaries of the weather. Extensions to the sleeper road being completed, and the water pipes from the tanks relayed underground to prevent freezing. The major task to date has been the establishment of a total inventory for the island , covering every nut, bolt and screw on the station. A task which took up the whole of the summer - all one day of it.

Visitors have abounded, our first Orion dropped newspapers in November and shortly after the 'Aquatic Explorer', a seismic survey ship, arrived to shelter from the westerlies while working to the south of the island. On a flying return visit George Money was taken off to return to New Zealand. Instead of making it back he returned on the ship’s visit the following week, the storm forcing them to seek shelter for a second time. George reached home on Christmas Day with the good favour of the "Hunt Oil Co."

Christmas was celebrated in true Campbellian style. Father Christmas, wearing gumboots, and a beard liberally coated with staving cream arrived to distribute the presents. A guest of the dinner was Gerry Clark, a yachtsman completing a single-hand circumnavigation of New Zealand and its outlying islands to raise money for the Stone Store Appeal at Kerikeri. During his stay of a fortnight the team were all lucky enough to get a sail around the harbour. One or two regretted their luck, as they were sea sick and on one particular trip, the boat received a knock-down. It is held on good authority that the crew on that occasion were mentally measuring the distance to the nearest shore via swim power . (Gerry also called at the Chathams, where he met several ex-Campbellites and we have since heard that he has reached home safely.)

New Year's Eve proved a highlight per favour the Russians who appeared with Professor Deriguyin early in the morning. We were able to sample their hospitality and spirit - as were entertained through their their New Year's celebrations on board. The ship called, coincidentally, to make engine repairs before departing south for the ice the following morning. The island was generously given a Russian barograph and ten hangovers.

The belated appearance of the 'Burton Island' saw the delivery of a new GMD and Brian Plummer along with Paul Johnstone and Tim O'Neil from the DSIR, the latter two arriving to erect a new aerial on Beeman, and check out the Ionosonde. To add to the mounting pile of newspapers an Orion dropped a sonar cannister on the following week, for which thanks go to Whenuapai Met.

Despite the weather, tramping and photography remained the most popular sport. Unfortunately, the rats have gutted the Bull Rock Hut. To repair it, a full scale packing trip was organised and struggled out into the sleet -very much in the spirit of Oakes 'I'm just going outside.'

It seems this year has been the year of the yachtsmen, when in February the yacht 'Maruvale' arrived from Dunedin via the Auckland Islands. (We have been maintaining regular radio skeds with the Auckland Island wildlife party who seem to be having a very successful expedition) Another visitor of the avious variety in the form of a Siberian Tattler made its first recorded appearance this far south. Mark Crompton has spent several days lurking to photograph it, we suggest he disguise himself more thoroughly in his "feathers." Mark has been the main bird man for the last couple of years.

During the first few weeks, Friday nights were associated with crisis. Firstly - a group spent a chilly evening behind Shoal Point waiting for the sea to abate before they could return. Another group spent a better Friday lost in low cloud on Azimuth. It almost became necessary for people to be confined to their rooms on Friday evenings. However, this has been overcome and we will look forward to a successful year.

Graham Camfield.

************************************

RECOMMENDED READING:

WRECKED ON A REEF

By F.E. Raynal

Nelson & Sons London 1896.

The publishers picked up the tale from the French "Les Naufrages des Auckland Iles" long after the event had left its lifelong impression on the castaways from the Australian schooner 'Grafton.’ Possibly nothing has been lost in the translation and the reader emerges after a 350 page immersion feeling as dusty as the Victorian prose contained within its finely embossed covers. To accentuate the period, 40 full page pen illustrations lead the actors through their agony and put the clampers climatically on the Auckland Islands by casting leaden skies for every backdrop. They are never-the-less fine examples of the engravers' trade.

On the 12th November, 1863, Captain Thomas Musgrave hopefully set out from Sydney in the rugged schooner-collier 'Grafton', with pick and shovel to reopen the tin mine on Campbell Island. Where he got the notion of this rusty cavern is not related and the truth of its absence was quicker to discover than hopes of untold wealth. To patch the pocket, they set sail for the Auckland Islands to try a little sealing, arriving in Carnley Harbour on December 31, 1863. A good stiff Southerly put the ship and crew ashore in the harbour's northern arm and so the eighteen month sojourn commenced.

Undoubtably Raynal was the brain behind their survival and led the the others through a period of time consuming projects which eventually climaxed their escape. Though lean in belt during the latter months of the Winter of '64 due to the exodus of the seals, they maintained sufficient stamina to put in a working day that commenced by first light and terminated at midnight. Their house measured a generous 24 by 16 feet with the roof apexing at 14 feet, and the six foot fireplace consumed "a cart load of wood a day." The rigging of the of the noble 'Grafton' held all together and some 5000 one pound bales of tussock were plucked to resist draughts up to seventy knots. Meanwhile over the hill a sealskin set of bellows blew locally into a pile of charcoal and Raynal bent his back to the anvil and fashioned sufficient tools from the schooner's ironwork to commence work on the escape craft. The 'Grafton' was well beyond salvage so the ship's 14 foot pram went through a series of modifications which brought it eventually under the classification of a cutter rigged submarine.

The escape took place on the 19th of July '65, Musgrave, Raynal and Alexander Maclaren barrel-rolling their way north to Stewart Island in gale force southerlies to summon rescue for the two left behind at Carnley. The sixteen ton cutter, 'Flying Scud' finally repatriated George Harris and Henry Forges to New Zealand on Thursday August 24th '65. Totally unknown to the five until sometime later, was that a parallel course of survival was underway at the northern end of the Auckland Islands. On l0th May '64, Captain George Dalgarno had managed to pile the 888 ton 'Invercauld' onto the rocks at the main island's north-western tip. Of the 25 crew, 19 made shore and only three had survived the processes of starvation by the end of August. They were rescued by the Portuguese ship 'Julian' in late May of '65, only two months before Raynal went thundering past on his errand of mercy.

|

|

|

|

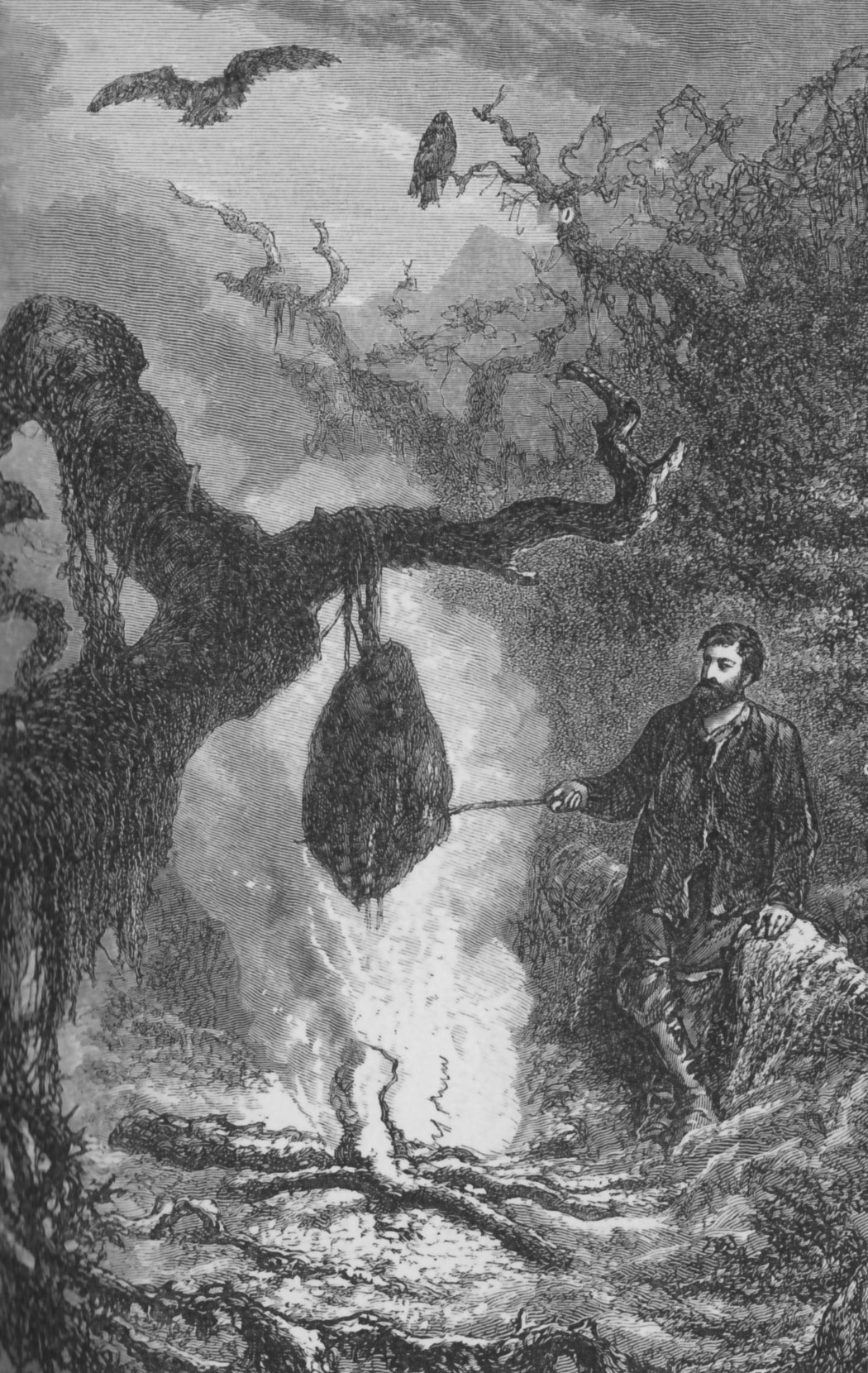

The Graftons Crew: Back L-R Raynal, Harris, Forges. Front L-R Musgrave, Maclaren |

Southern Barbeque: of seal meat was a daily happening. |

CASTAWAY ON THE AUCKLAND ISLES

By Captain Thomas Musgrave

Lockwood & Co London 1866.

‘Castaway’ is the companion piece to Raynal's account. Running mainly in journal format, Musgrave starts with their arrival at the Auckland Islands, but lacks Raynal's power of description so that the book commences its usefulness when two thirds read: This final third contains a full account of the return to Carnley in the 'Flying Scud' and examination of the Port Ross area for any others stranded by faulty navigation. Musgrave found little evidence of Charles Enderby's earlier colony which had been deserted only 13 years previously. Where was the town of Hardwicke ? It had measured eighteen houses by a half mile main street, and had terminated with workshops, slip and jetty as well as barracks and a battery of four cannon. The industry of a population of 300 over three years was now only represented by a few overgrown sections of rock paving and flat foundation sites. Obviously they had packed more than their bags for their departure in '52.

Musgrave was a master mariner and a reasonably careful one at that. How he managed to put the 'Grafton’ in such an erroneous position on the night of the big blow would be beyond the most humble Hauraki yachtie. His subsequent remorse and teeth-gnashing illustrates the commencement of the earlier chapters and he would undoubtably have become a nut-case if Raynal's drive and enthusiasm had not been present. To his credit he logged an enormous amount of meteorological data on the Aucklands and later conducted night classes in reading and writing for the less educated crew members. He also attempted to run the house as a ship and was peeved when his rank lost its full recognition. The ‘men’ remained nameless in his account until it was necessary for some form of human identification at the time of rescue. Such were the processes of rank at this earlier time.

For all the book's sombre tone, it has managed to remain a literary mine of information and must have enthralled its candle-lit readers of a century ago. The last thirty pages supply appendices on sea lions, history and description of the Auckland Islands and Dalgarno’s account of the loss of the 'Invercauld.' Had Musgrave been a little more skillful on that stormy night in 1863, so history would have been made a little poorer by his caution and foresight.

Pierre.

***************************

My apologies to those who got early wind of the barbeque to be held outside our residence at Makara on February the 17th. As you probably know, there has been a high fire risk in the area which forbade even beach fires .

Tony Bromley.

****************************